Anna Dunnill & Danni McGrath discuss Lucas Ihlein: Diagrammatic, curated by Jasmin Stephens, Deakin University Gallery, Melbourne, 11 April—18 May 2018.

We (Danni and Anna) are both artists and we live together in a Centrelink-approved partnership, but we don’t really collaborate artistically. We get asked about this a lot. In fact, we do both have collaborative practices, but with other people, not each other. Our collaboration style as partners is the everyday kind, making dinner together while talking through the ideas and processes we’re separately investigating.

Partly as a way to formalise some of our ongoing conversations, we decided to respond together to Lucas Ihlein’s survey exhibition Diagrammatic. A collaborative response seemed appropriate because Ihlein’s artistic practice nearly always involves working with other people—the exhibition wall text features a foot-long list of collaborators.

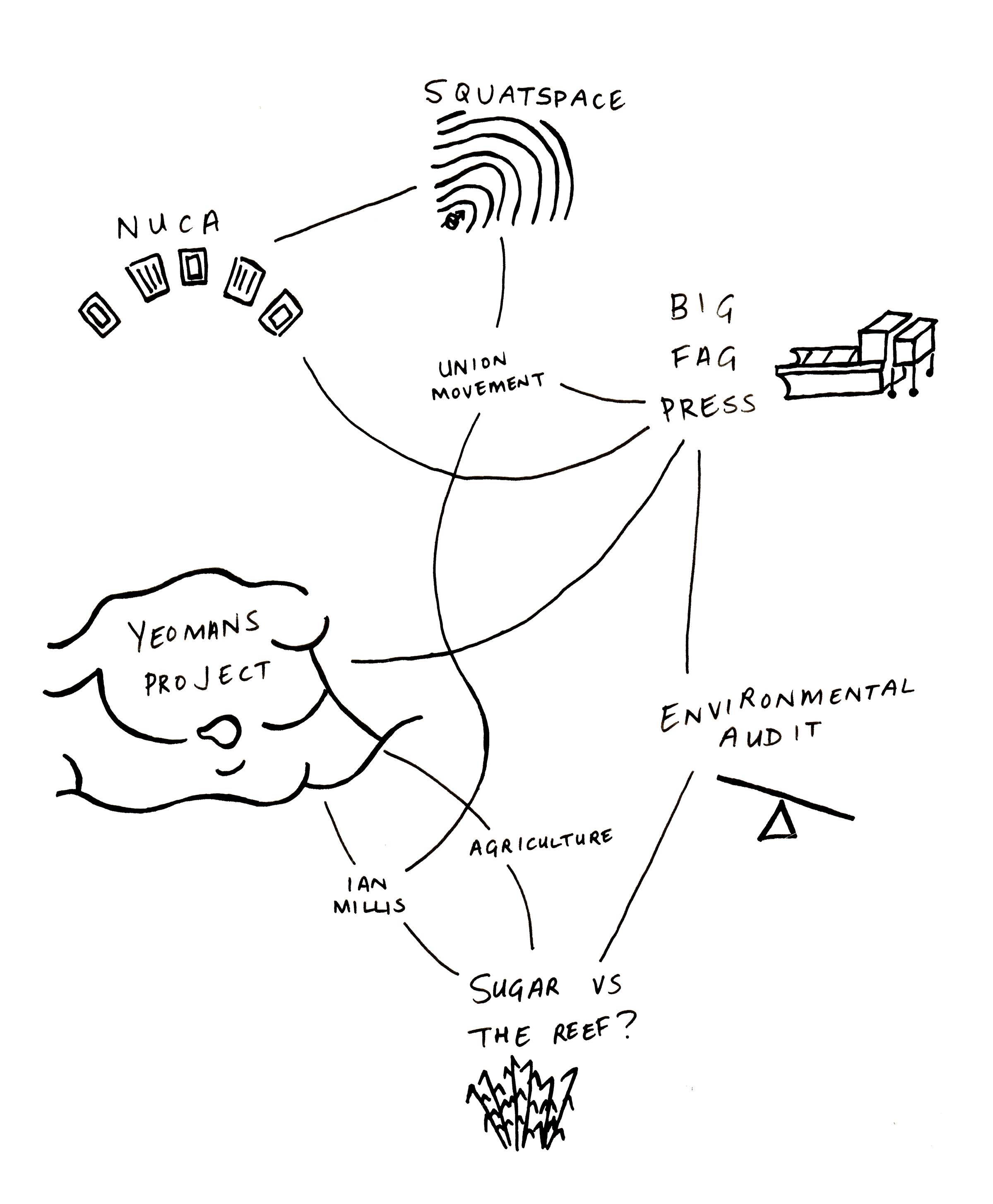

Whether setting up a squatted art gallery, establishing a collective print studio, producing artist trading cards or engaging with sugar-cane farmers, Ihlein is never the sole player. A site-based researcher, his practice returns often to print- and publication-making; these artefacts have become the throughline of this survey exhibition curated by Jasmin Stephens. Using maps and diagrams to trace the connective networks within each body of research, Ihlein illustrates the human impact on the environment and each other.

The following text is distilled and edited from an initial conversation.

Danni: I was first introduced to Lucas’s work through his printmaking practice—we were shown the work of Big Fag Press [1] in a first year printmaking class, as an example of a conceptual approach to print. Being introduced to that project in art school sparked something because I was learning about printmaking and excited about it but also very much aware of its limitations.

Anna: When I’ve talked to you about Lucas’s practice in the past, it’s always been framed through printmaking. But looking at his broader body of work, it’s clear that, actually, the printmaking is more like a way—one of many ways—to have an outcome from a body of research that’s almost always engaged with the site, community living, our impact on the environment.

D: I don’t really see Lucas as a ‘capital P’ printmaker—he’s an artist who uses print. His work exists in a socially engaged context, over that of art-object culture—he sets out to do something with a site or a community, and then a print is made to commemorate or document or share what happened.

A: And frequently the projects are communicated through blogging—which in many ways is a more efficient means of recording and distributing the research process! So, yeah, his work is not necessarily focused on creating a physical, archival print object.

D: Which makes a lot of sense, because the things Lucas investigates are often concerned with sustainability and environmental impact. This is something I’ve been quite aware of with my practice—there are so many things that exist in the world already and I have some anxiety about creating more things.

For Lucas, the physical objects that do end up being produced, whether they be books, prints or trading cards, [2] stand in for the embodied work that’s been done: conversations, researching, site visits, consultations, thinking, connecting the dots.

A: In this exhibition, though, the physical things are what we’re left with. One or two objects from each project have to represent enormous bodies of research that can’t be seen.

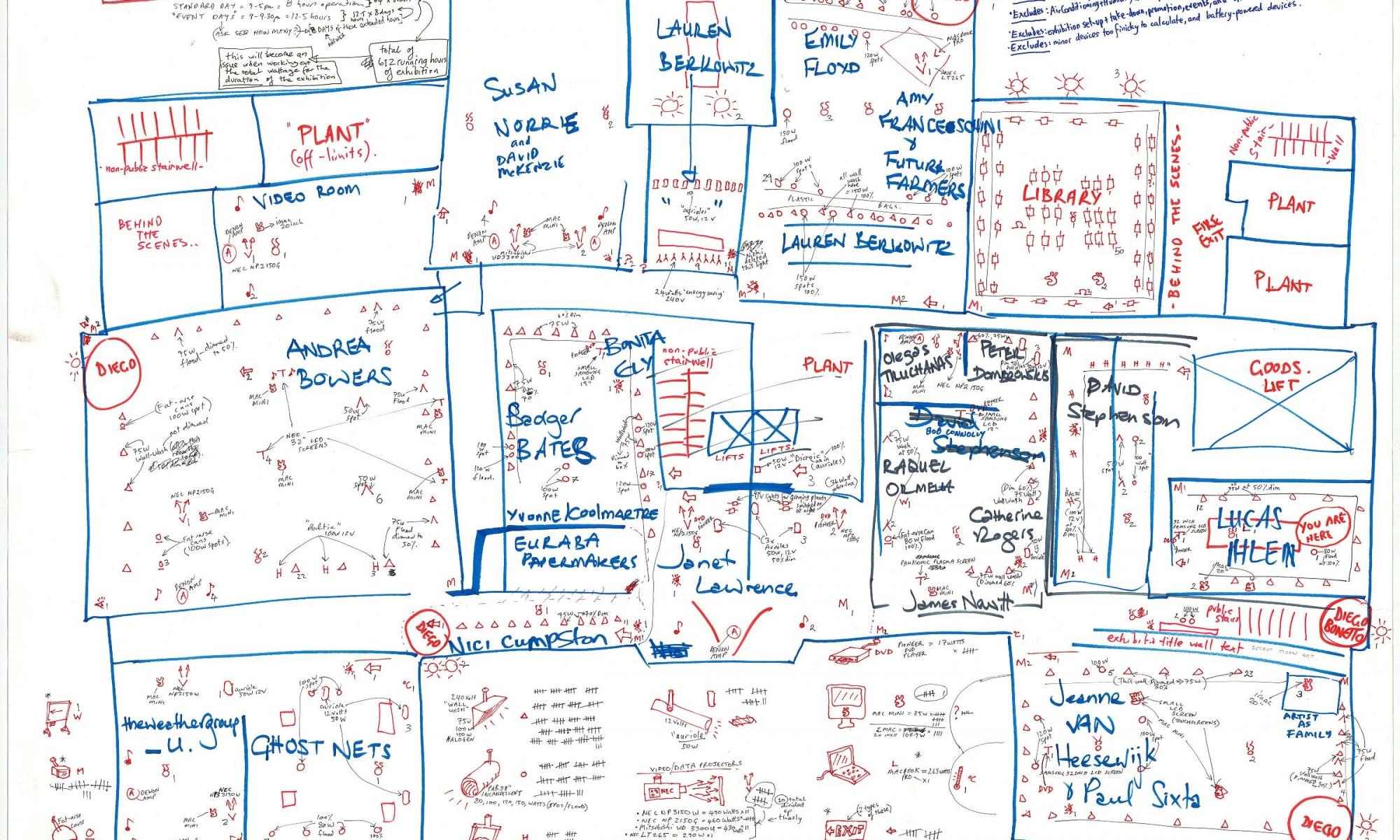

The Environmental Audit artist book allows us inside the process of that particular project, [3] more than any other, through the reproduction of blog posts, photos, and diagrams from the time. It was 2009 when Lucas was doing Environmental Audit, and among other things, he recorded all the unique page visitors and downloads for the project blog and included them in his total estimate of energy use. It’s kind of amazing that we still think about going digital as being an environmental problem solver—but all digital data has to be stored somewhere! In physical buildings that exist and use energy!

D: Something that this exhibition, and Lucas’s wider practice, succeeds in doing is making visible certain things that are normally invisible, such as the footprint of digital data, or a historical event that was only witnessed by the people who participated in it.

I’m thinking particularly of SquatSpace Network Map that shows the evolution of SquatSpace [4] from the Broadway Squats space in 2000 to all the associated events, initiatives and projects that it spawned. The squats only existed for about a year, but this timeline shows all the ripples—all the people connected to that, all the things they’ve done since then. Big Fag Press is in there. It shows how this one thing that happened in Sydney—a community of people squatting, protesting and making art, has gone on to influence all these other things that have happened around Australia since.

A: Yeah, the diagram isn’t so much about SquatSpace itself, but about tracing these different trajectories and changing communities. This carries through many of the works—making visible the impact of a community. Or the impact of an individual; or, as in The Yeomans Project, [5] our direct interaction with the land.

Talking about impact, is it the purpose of these works to be useful? They’re very much on the brink of art and activism.

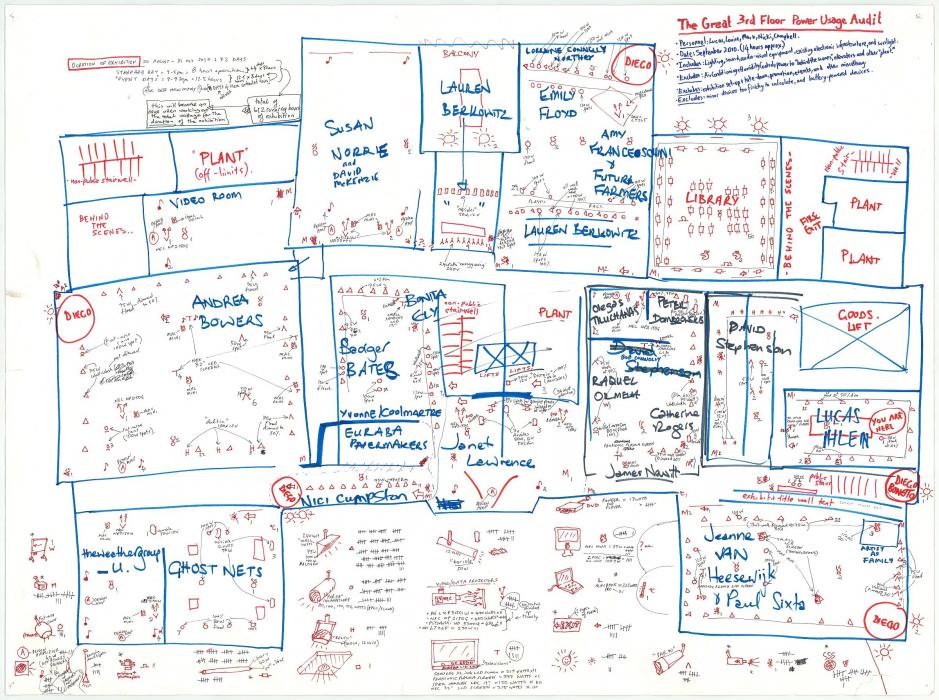

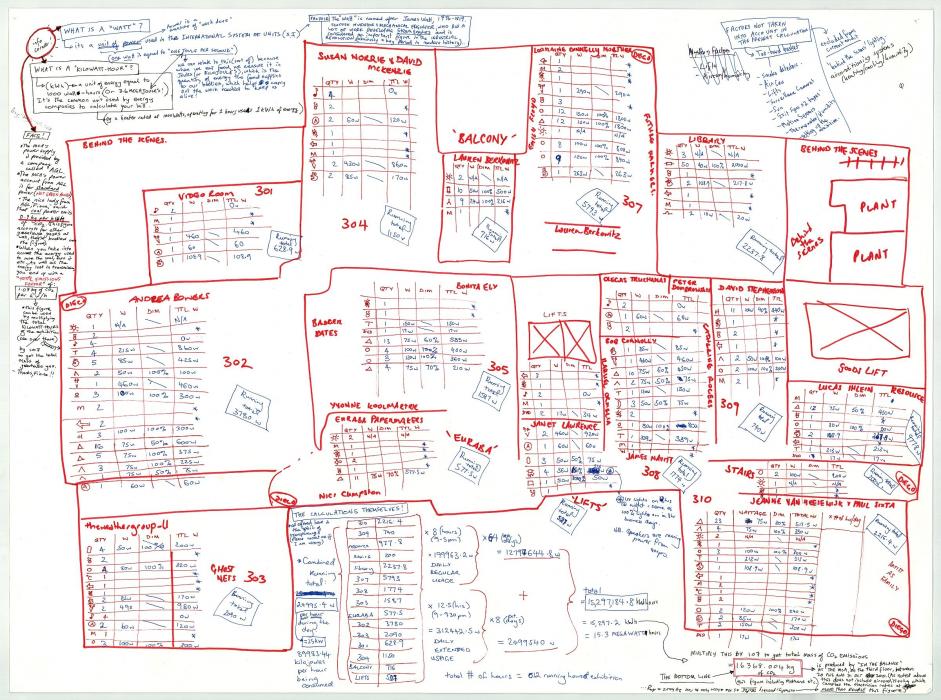

In Environmental Audit, Lucas diligently came up with his own systems for understanding how to audit, from the very basics. He drew pictures of the different kinds of light fittings in the MCA galleries and logged how many of each light fitting was in every room of the exhibition. On one of the blog posts documenting this process, someone commented: ‘You know, your results aren’t really going to be very reliable and really an audit needs to be undertaken by a proper engineer or it won’t mean anything.’ And Lucas very diplomatically replied—I’m paraphrasing—‘Well, you know, I’m not an engineer but I’m just doing my best and learning as I go.’ [6] He pointed out that part of the project is to figure out what an ordinary unskilled amateur can do.

The final energy output figure was huge, you know, air-conditioning going 24 hours a day, lights, screens, etc. And the obvious question is whether that environmental impact is worth the conceptual and ideological impact of the art being displayed. But he deliberately never makes a judgement about that; he just presents the facts as he’s found them.

D: Yeah, it’s not about coming to a conclusion about that exhibition or event, it’s about pointing out the process. I look at that and immediately I’m thinking about our home, or my studio, or what I make. What’s the equivalent environmental consumption of the places we interact with every day?

A: So it’s really more like a tool that illuminates it for us—in a language we can understand, because Lucas is figuring it out himself.

D: Exactly, and that’s the value of Lucas instead of an engineer, because an engineer is (usually) not going to produce something that’s accessible—a blog post or a diagram scribbled on butchers paper—that we can understand.

I wonder if that accessibility is something that’s being pushed with Sugar Vs the Reef. [7] The project is still in development, so in Diagrammatic we only see three artefacts from it, including a Channel 7 News report on the symphony in the sunflowers. It’s this one minute segment on a youth symphony orchestra performance that is about to occur in a sunflower field, on a farm in Queensland, where the farmer has decided to plant sunflowers because it will replenish the soil for subsequent sugarcane crops.

You don’t get more mainstream than Channel 7 News, so this project is reaching more and more people.

A: It’s interesting that this piece from Channel 7 is presented as an artistic outcome. It’s basically the opposite of a high-end archival fine art print, but this is what’s shown in the gallery—the project interpreted through a mainstream lens.

The segment starts off: ‘This is “Art!”’, with a panning view from above of a bare patch in a sunflower field. The implication is that everyone’s scratching their head, like, ‘what are those weirdos up to now?’

By including Channel 7’s viewpoint in the gallery, the project’s authorship becomes even more collaborative.

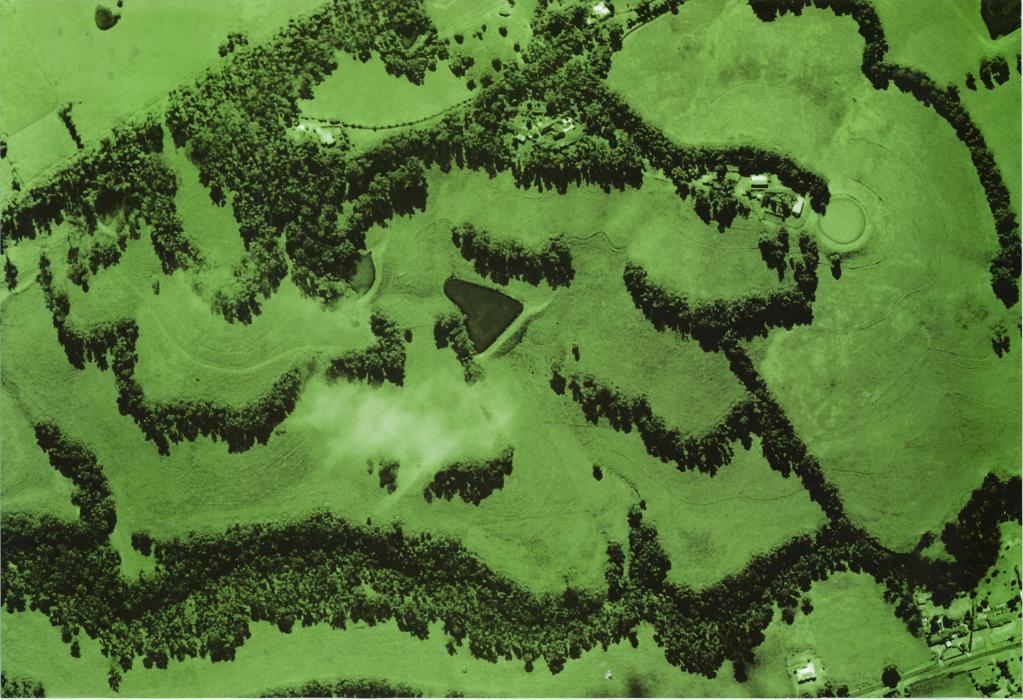

D: It’s a logical extension of the research around The Yeomans Project, which looked at the archive of P.A. Yeomans’ work and re-framed his Keyline irrigation concepts (essentially, the origins of permaculture) as ‘land art’. That project focused on renewing interest in existing ideas that could help shape and improve farming practices. Within the commercial agricultural field in Australia, Yeomans’ work hasn’t had that much impact in practical terms of actually being implemented on farms. I think about the Wheatbelt in Western Australia where I grew up visiting my grandparents, the land is kind of ruined. There’s a lot of unrealised potential in the Keyline concepts that could have saved the landscape if they were implemented.

And Sugar Vs the Reef is now looking at facilitating projects that put Yeomans’ principles into action. The reef is being affected by all sorts of things but a crucial component is the runoffs from sugar cane farming—fertilisers and pesticides, things artificially added to the crop to aid its growth. The Keyline principles are about mitigating the large-scale impact of farming on the environment—working with the environment, rather than against it—and that’s what this project is championing, in a very real way.

It’s also about locating where an impact can actually happen: the Great Barrier Reef is this relatively discrete thing that all Australians connect to—so you can actually galvanise a community into action.

A: It’s using art and grassroots activism towards a real-world outcome—really asking sugar cane farmers to reconsider their approaches. The potential outcome the project seeks is more than a print or a blog or an idea—although those things might happen—but a recommendation that’s carried out long-term, something that changes in the way we impact the world.

[1] Big Fag Press (2004-ongoing) is an artist-run printing collective, of which Ihlein is a founding member. Big Fag Press is centred around a four-tonne FAG offset lithographic press and works with artists, designers, and activists on collaborative print projects.

[2] Made for the 2004 Next Wave Festival, Network of Uncollectable Artists exists as a set of 50 trading cards, each featuring one of the ‘most un-collectable’ Australian artists of the time, that is, those working in ephemeral or performative media. The list was, in part, a satirical response to Australian Art Collector magazine’s annual list of 50 Most Collectable Artists. Network of Uncollectable Artists was produced by Jimmy Sing, Hana Shimada, Keg de Souza, Mickie Quick and Lucas Ihlein (and all the artists on the cards).

[3] Lucas Ihlein, Environmental Audit, 2010, exhibited at Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney.

As part of the 2010 exhibition In the Balance: Art for a Changing World at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Ihlein was commissioned to undertake an audit of the exhibition’s environmental impact. The audit was carried out over the four month run of the exhibition in the form of an artist residency within the gallery space. Environmental Audit was documented in the form of a blog (environmental-audit.net) and a series of lithographic prints created at Big Fag Press.

For Diagrammatic, Ihlein compiled a number of blog posts, images, and other outcomes from Environmental Audit into a publication for visitors to take away.

[4] SquatSpace is a collective that began as an art and event space in the Broadway Squats, a community residential squat in an Inner Sydney council-owned vacant building that ran in 2000—2001. The SquatSpace Network Map (2011), included in Lucas Ihlein: Diagrammatic, is a large wall-sized timeline made up of chalkboard panels, overlaid with radiating bands, each representing one year since it began. SquatSpace associated events, initiatives and projects, as well as key national and global news events, are recorded across the map. Video documentation from the Broadway Squats, focusing on the negotiations between squatters and authorities is presented alongside the map.

[5] The Yeomans Project (2011-2013) is a collaborative project by Lucas Ihlein and Ian Milliss, investigating the work and influence of PA Yeomans. Sustainable agricultural systems developed in the 1950s and 1960s by Yeomans comprise the origins of contemporary permaculture. The project re-frames Yeomans’ work as a form of ‘land art’—a concept first proposed by Ian Milliss in the 1970s.

[6] For Sugar Vs The Reef (2015-2019), artists Lucas Ihlein, Ian Milliss and Kim Williams were invited by a farmer and environmental activist John Sweet to investigate the effects of sugarcane farming practices in northern Queensland—particularly the resulting degradation of the Great Barrier Reef. This ongoing project involves a wide range of collaborators and includes experimental planting techniques, public events in an amphitheatre carved in a sunflower field, and an exhibition at Artspace Mackay in late 2018.

-itok=NVm-0NPP.jpg)