Into My Arms, Curated by Frances Barrett and Toby Chapman

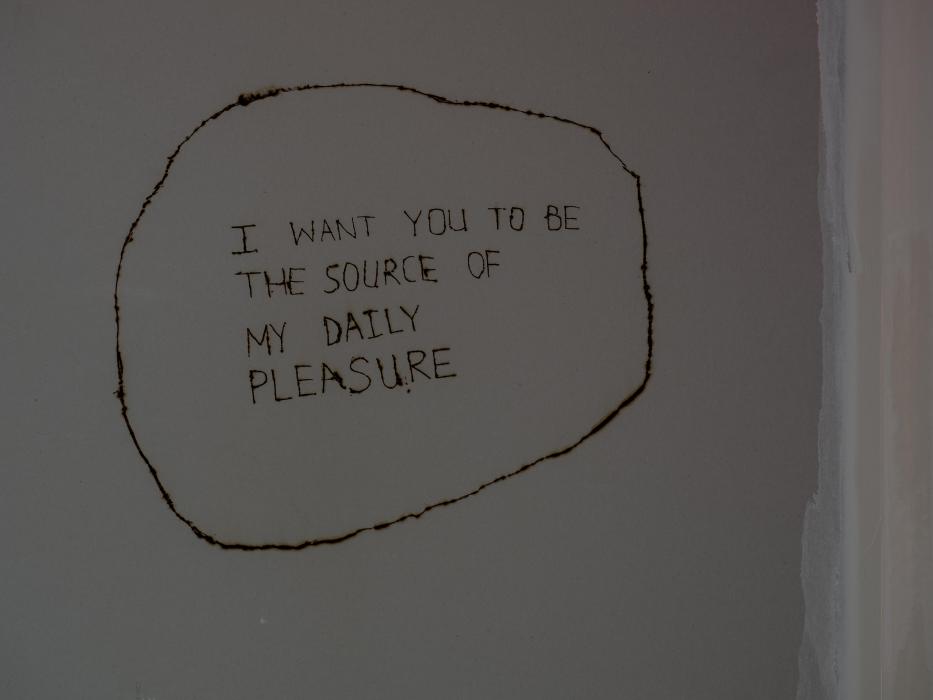

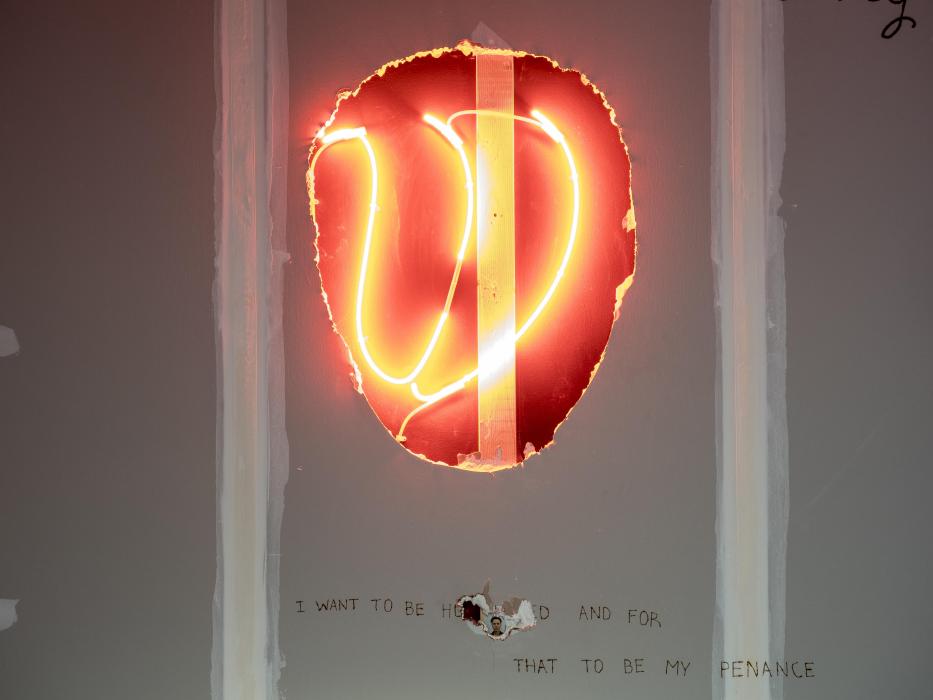

A cowhide spread on the floor reads POWER FUCK. The letters are traced with metal studs hammered into leather, through skin. Beside them, a red neon illuminates a plasterboard wall. Words scrawled blotchily on the surface of the wall: I want you to be the source of my daily pleasure. Below, another sentence: I want to be humiliated and for that to be my penance. The word ‘humiliated’ has a hole punched right through. Inside the hole is a passport-sized photograph of the artist. We’ve never met, but I recognise her from Instagram.

Installed in an alcove just outside the main space, this is Athena Thebus’s 2018 work Dreaming about you woke me up. As the first piece encountered in Into My Arms, it’s a strong opener: I am jolted into a queer embrace that grips like a vice and orders me to let go, spells out—wordlessly—the different implications of fist.

‘In a time of social and political precarity, how can an “embrace” enact a form of resilience and care?’ [1] This was the provocation given by the co-curators of Into My Arms, Frances Barrett and Toby Chapman, who commissioned all-new works for the exhibition. Two days of performances and public programs occurred at the beginning and end of the exhibition period, within the gallery. Most of the performances took place during the first one, but I’m visiting Adelaide in the show’s last days; the remnants from the first event—photographic documentation, some written texts and verbal descriptions—will have to be enough to conjure these flesh experiences.

In Thebus’s performance, the artist knelt beside her work to read aloud her text DOGGY, 2016. The writing on the wall is lifted from DOGGY, which is reproduced in full in the exhibition catalogue. Being a dog is how I want to move through this world, Thebus writes, channelling submission, adoration, gnashing teeth. It’s raw and discomfiting, and seductive.

Moving into the gallery, I sit down with Amira.h’s two-channel video, Life Online with @amiraball, 2018. For a year the artist conducted ‘the majority of her social life online’ via live-streaming app Periscope, as an endurance performance. [2] 150 live-streams over a year—or one every 2–3 days.

What does it mean to interact ‘mostly online’? How is it different from the way we all interact now anyway? A tweet I saw recently by someone called Liam Williams, aka @funnylad5:

1997: I am *surfing* the web

2007: I am *browsing* the web

2017: There is no verb for my useless, constant state of being

This has been re-tweeted over 21,000 times.

In order to write this review, I have activated a plug-in on my laptop called SelfControl, which prevents me—for a set period of time—from accessing websites that suck me into an endless dreary scroll from which I may never emerge. I have to use an app for self-control because my own stores have been eroded. This is an act of care.

Life Online is shown on two screens, arranged around the S-shaped padded seat, so that visitors sit in the curves of the S, facing opposite directions to watch it. On one screen is a video of Amira.h’s last broadcast on Periscope. The artist muses about her experiences using the app, interrupting herself to read out the live comments that pop up at the bottom of the screen, text bubbles that are pushed upwards as the scroll of conversation unfurls. Many demand that she shift the camera down to show her breasts. The few respondents that attempt to participate in her conversation are quickly moved up and out by the clamour of misspelled questions, compliments and veiled demands about Amira.h’s appearance, her body, her tattoo (a cupcake with Smurf-blue icing, on her upper chest). She’s bare-shouldered, she seems to be in bed with the blanket pulled up to her armpits, mouth red-lipsticked. She ignores the pleas to ‘show titties’. I wonder about the people—men, judging by their profile avatars—making these requests. Aren’t there enough tits to be found online without demanding more? Part of the allure must be the illusion of a conversation, of request and compliance, of a bond between consenting partners. Amira.h does not provide this.

A periscope is the lens that a submarine pushes up and out of the water. Who’s down in the submarine / who’s on land? Instead of an engagement at a deep level, this is a sustained engagement with the surface. The same thing happening over and over, 150 times.

The other screen shows a series of stills and snippets from Amira.h’s various Periscope broadcasts across the year. In one segment, a viewer asks what’s going on. ‘Amira is sleeping,’ another replies, their text bubbles drifting upwards over the image of the artist tucked in bed. I recall a similar scene in The Truman Show, when Truman is asleep, but still being broadcast live to the world. Released in 1998, The Truman Show pre-dated—predicted?—the explosion of reality television. On the show within the movie, live footage of Truman sleeping presumably took up half the time on his dedicated channel. In 2018 we all think we are Truman. The ocean jostles with single-person submarines, periscopes pushing up into the empty air.

The video of Amira.h’s broadcasts runs for over four hours, but although I visit twice I seem to hit the same spot in her very last broadcast both times. It’s introspective, repetitive, kind of boring, the way I imagine Periscope mostly is. Amira.h addresses her viewers by their handles, greets those she recognises. Their interactions are fleeting. Some viewers are melodramatically devastated at the impending end of their Periscope encounters—‘when will we see u?!’—but as Amira.h points out, she’ll still be on Twitter. After twenty minutes of this I’m impatient to see her do something—read aloud, sing, talk about the things happening in her life beyond Periscope, perform—but she’s just here, online, present in some form, and I think that’s the point.

Kate Power and Susie Fraser’s collaboration, Stories from the Interior…Em/Brace, 1999/2018, is an experiment in studio play, fragmentation, and care. Fraser’s work is a video shot in the late nineties; in the roundtable discussion she says this was a way for her to begin making art again after having children. Its wobbling, blurry shots show the artist, the ghost of her past self, within a domestic interior. A grainy close-up of her face. In the paired video, Power’s hand (her tattoo is a giveaway) moves over a wall’s rough painted skin, caressing its lumps and bumps. In another shot her body, in a turquoise bathing suit, floats partly submerged in a pool, arms outstretched; she looks like Ophelia.

During the roundtable discussion, Power and Fraser describe the experience of collaborating. They had not worked together previously, and their collaboration occurred mostly long-distance, over email. Both were struggling to make new work—Fraser paralysed by anxiety after time away from the studio, Power drained from several back-to-back residencies—and the collaboration allowed them to breathe out, rest against one another. They don’t describe it like this, but that’s what they convey. In another segment of Power’s video, she stands with her back to a wall. Pushes against it. Moves up, down, sideways, always touching, always braced.

All of the works in this exhibition convey something of the impossibility of human connection: a feeling of never quite reaching. The room is darkened, austere. I have a bias towards tactile work, softness and lumpiness, bodily gestures; perhaps this is what I automatically expected from an exhibition about the embrace? In actuality much of the work in Into My Arms is hard, sparse, trapped behind the glass surface of screens. I want to tap on the glass, fall through. A deep ocean hums between spots of light.

In Eugene Choi’s work—My mother only speaks Shanghainese when she talks to her brother on the phone (these plants are a gift for her), 2017—even the screens are turned away from each other. At either end of a long scaffolding structure, the screens bracket a row of house-plants held close to the ground. The plants are placed in bright plastic baskets. On one screen, a woman (presumably Choi’s mother) talks on the phone in what must be Shanghainese, her body and face turned away from the camera. On the screen at the other end of the scaffolding, the artist and her mother dance together in a clumsy synchrony, imitating movements on the TV screen. The lounge room is decorated with different house-plants, also in plastic baskets.

Perhaps more than any other, this work highlights both closeness and distance. The rupture of language and culture through diaspora. The hardness of tubular steel holding up—bracing—the two videos, stand-ins, perhaps, for the bodies of Choi and her mother. The affection evident in the gift of plants. The two figures, mother and daughter, dancing side by side, laughing together without touching.

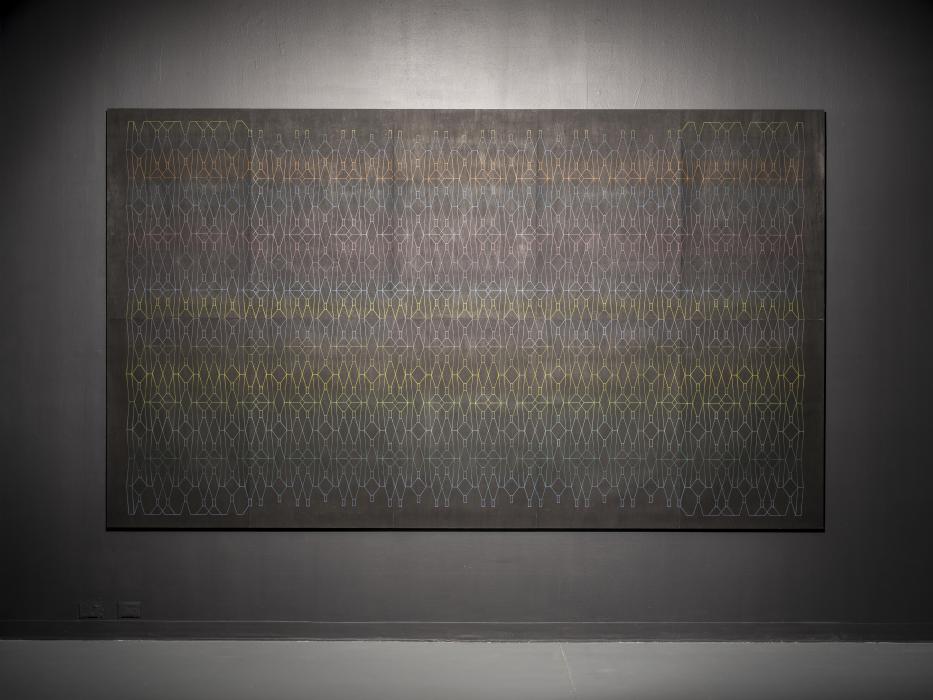

The scaffolding structure in Choi’s work is echoed in Matt Huppatz’s 2018 paintings, Portal Form (Net Work 1) and Portal Form (Net Work 2): precise, delicate rainbow nets hovering on black. Huppatz’s work is often about spaces of queer community, and this rainbow net seems like a glimmer of utopia: a structure that holds itself up, each segment crucial, glowing in the dark. Is this portal the alternative to those dozens of submarines banging against each other in the ocean? How do we reach it?

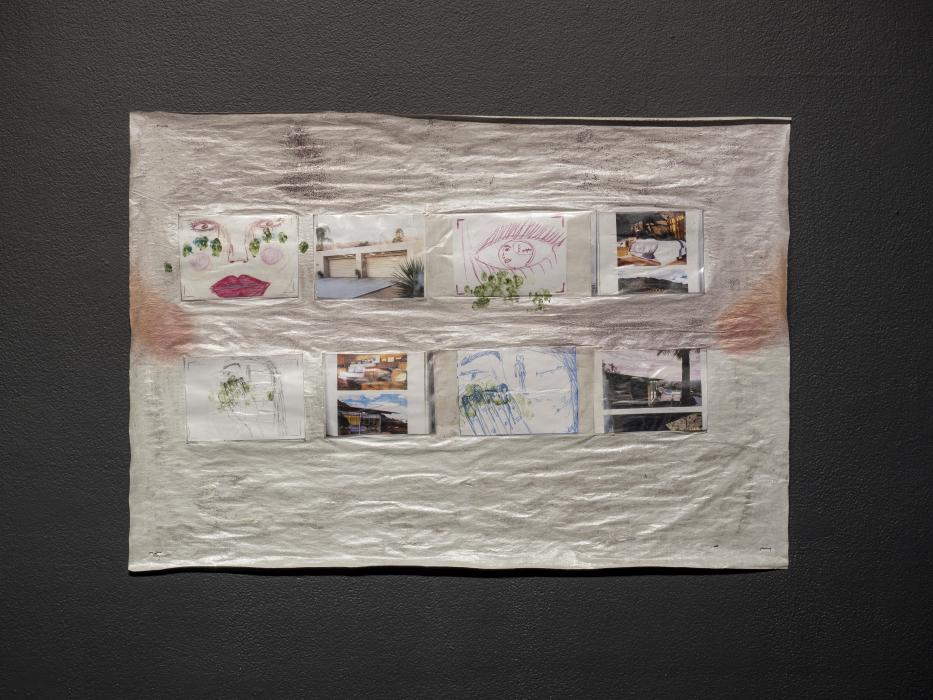

Alone in the back corner is Katherine Botten’s Untitled (showing up for my life), 2018. An A4 collage on newsprint is adorned with what appears to be makeup—smudged eyeshadow or blush, a pearlescent shellac. The coated paper has wrinkled; is pinned stretched out, skin-like. It recalls the cowhide of Thebus’s work at the opposite end of the space, but thin and fragile where Thebus’s was tough. Botten’s accompanying text work is a fragmented stream-of-consciousness, a litany of anxieties interspersed with lists of beauty products, art products, self-help mantras, spells. There’s a list of the artist’s best friends by first name. I don’t know the artist, except recognising her from Instagram, but based on this list I can tell our circles overlap.

Botten’s text feels like it was written on the Notes app; it feels like an endless scroll. If this is an embrace, it’s an embrace of the self in a post-internet world: the raw, wounded, ugly self, drained and overstimulated, popping painkillers and downing coffees, using a different eyeshadow each day to manifest change. Scrolling twitter, your body hunched into itself, every caress of your thumb on the screen a gesture towards absolution, towards the future. Moving through this infinite loop, you’re searching for something magical to appear—just one swipe away, one tap—so you can throw yourself—finally, utterly—into its arms.

[1] Into My Arms exhibition catalogue text, 2018.

[2] ibid.

[3] Fanny Wonu Veys, “Capturing the ‘Female Essence’? Textile Wealth in Tonga”. In Sinuous objects : revaluing women’s wealth in the contemporary Pacific, edited by Anna-Karina Hermkens, Katherine Lepani. ANU Press 2017. ( http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n2571/html/ch08.xhtml?referer=2571&page=15#)

[4] ibid.