Craftivism: Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms

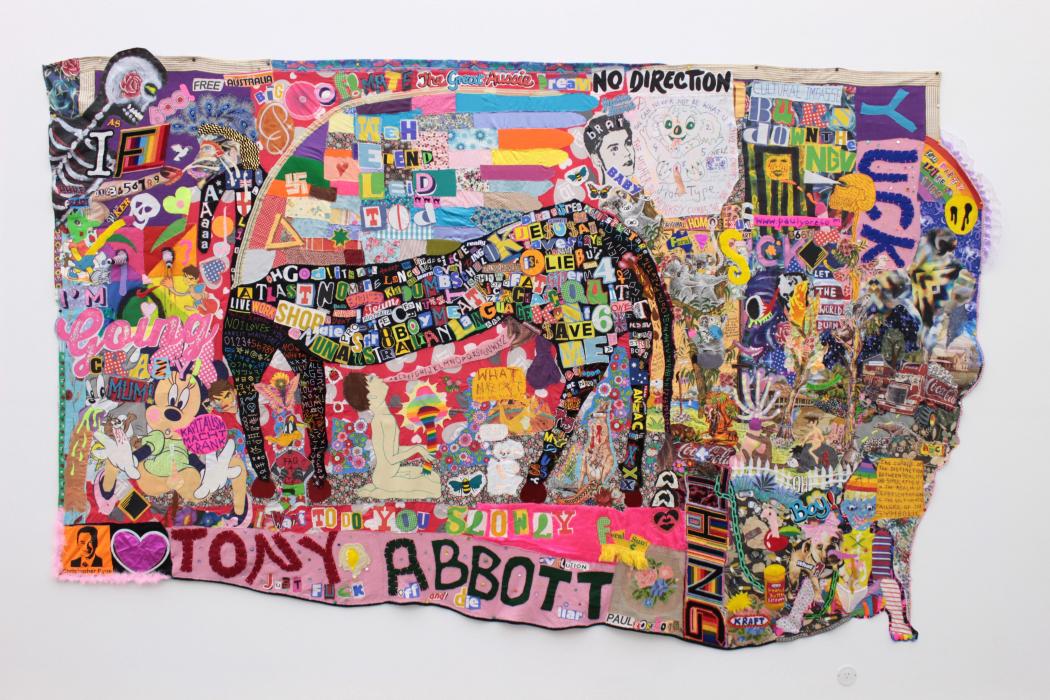

When I interviewed artist Paul Yore a couple of months back, I asked him about the reality of making his textile works: layered wall hangings that mash advertising, religious iconography, gay porn, homophobic slurs, cartoons and politics into an embellished, sequinned, appliquéd pop culture vomit with button trim. They’re humorous, but also confronting, lewd and deeply uncomfortable.

As a textile artist myself, thoroughly aware of the labour that goes into this kind of work, I wanted to know: isn’t it sort of unbearable? Spending months, years even, painstakingly articulating all the absolute worst, stupidest, most overwhelming aspects of contemporary culture? But Yore was emphatic in his response—‘It’s necessary, I would say’—describing it as ‘a survival mechanism.’[1]

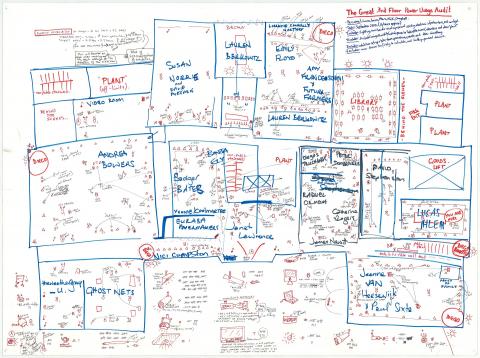

I have been thinking about this remark a lot in relation to the Shepparton Art Museum (SAM) exhibition Craftivism: Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms. Curated by Rebecca Coates and Anna Briers, this exhibition features eighteen contemporary artists, mainly from Victoria and New South Wales, whose practices intersect craft processes and politics. The definition of ‘craft’ is refreshingly loose, taking in the usual textiles, ceramics and jewellery as well as carved foam, collage-based animation and cast resin sculpture.

Despite the title, I actually don’t think that the majority of the works in this exhibition engage with ‘craftivism’ in the usual sense. (Some artists that I spoke to weren’t even all that keen about the label being applied.) ‘Craftivism’—a term coined around 2002 and popularised by Betsy Greer—implies an emphasis on political action over artistic and conceptual rigour; on employing craft in support of a specific campaign for change, rather than as a material response in its own right. A more usual application of ‘craftivism’ might be, say, the Knitting Nannas Against Gas (KNAG): a nation-wide network of self-described ‘women in their prime of life’ who weaponise craft in peaceful protests against fracking and coal. ‘We use the common stereotype of the sweet little old lady to lull the bad guys into a false sense of security,’ the KNAG website states. ‘The idea of the Knitting Nannas is that of the iron fist in the soft fluffy yellow glove.’[2] An idea I can wholeheartedly get behind.

While KNAG is clearly an activist group, outside of an art gallery many of the works in Craftivism wouldn’t even necessarily read as political. But crafts are embedded with historical meaning; heavy with implicit activism. In this exhibition, subversion and dissidence take many forms.

The expectations of gender, sexuality and restraint held within textile practice are unequivocally smashed by Paul Yore in his lavish wall hangings What A Horrid Fucking Mess (2016) and Art is Language (2017). Yore delights in sticking up two middle fingers to the notion of good taste; exhibition co-curator Anna Briers describes his work as having ‘the intrigue of a lavishly decorated men’s toilet stall located within a Country Women’s Association tea party’ (an endorsement definitely worth displaying in needlepoint).[3]

Raquel Ormella’s Blockade in my studio for the Pilliga Forest #1 and #2 (2018) have a more direct political target. Responding to the Santos Narrabri Gas Project, a controversial fracking proposal that threatens a large area of inland forest in New South Wales, Ormella turns the act of needlework into one of personal protest. The Santos project has incited rallies, blockades, and a record 22,700 formal submissions of opposition to the NSW Department of Planning.[4] (KNAG has been actively involved.) Here, Ormella co-opts the slogans from these protests—‘KAMILAROI LAND / SAVE THE PILLIGA FOREST’; ‘850 PROPOSED CSG WELLS’; ‘LOCK THE GATE’; ‘DEATH CULT’—and laboriously embroiders them onto scraps and offcuts of fabric. These, in turn, are stitched onto hi-vis workwear, a frequent material in Ormella’s work that stands in for the fly-in fly-out culture of mining developments.

By turning the studio into the site of the ‘blockade’, articulating her concerns in time-consuming stitches, Ormella makes a compelling argument for time—paying attention—as the key political action here. Once completed, each Blockade piece articulates the process of its own making; each compresses the energy of a mass protest into dense, palm-sized embroidery.

The Slow Art Collective’s Archiloom (2018) encourages visitors to contribute to a collaborative installation that similarly demands time and attention. In an ongoing project with numerous iterations, Slow Art creates architectural structures from bamboo and industrial rope; walls are netted or ‘warped’ so the whole structure is turned into a giant three-dimensional loom. On opening night, a number of visitors—including a number of teenagers—could be seen inside the installation, absorbed in the process of weaving.

Ghost net vessels 2015–18, by the Erub Arts collective in the Torres Strait, engage with the precarious situation of the artists’ local environment. Lumpy and textured, the vessels are woven from discarded fishing nets that drift through the ocean and wash up onshore, entangling sea life in their path. Traditional weaving skills form the nets into objects of dissent, a hard protest held within soft quiet forms.

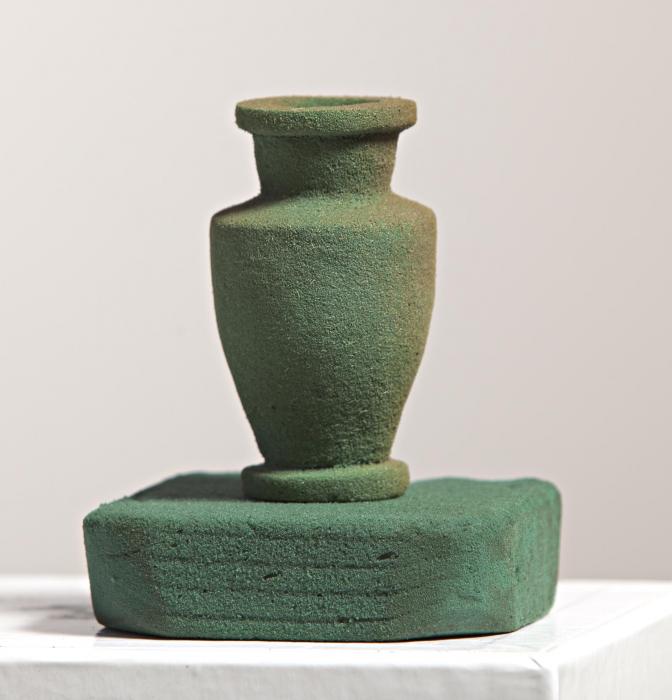

Another set of vessels, Catherine Bell’s Crematorium Vessels (2012–14), were produced during a residency in a palliative care ward. These elegant hand-sized objects are carved from florists’ foam, used to hold the flower arrangements delivered to residents, then gathered by Bell once it had served its purpose. Reminiscent of urns or perfume bottles, they are held behind glass; protected from dust, from our bodies’ flakes and oils. I’ve learned that this floral foam itself is a precarious material, made from micro-plastic of the sort that is seeping out of our synthetic clothes and into our water supplies at an alarming rate. There is tension between these different forms of decay.

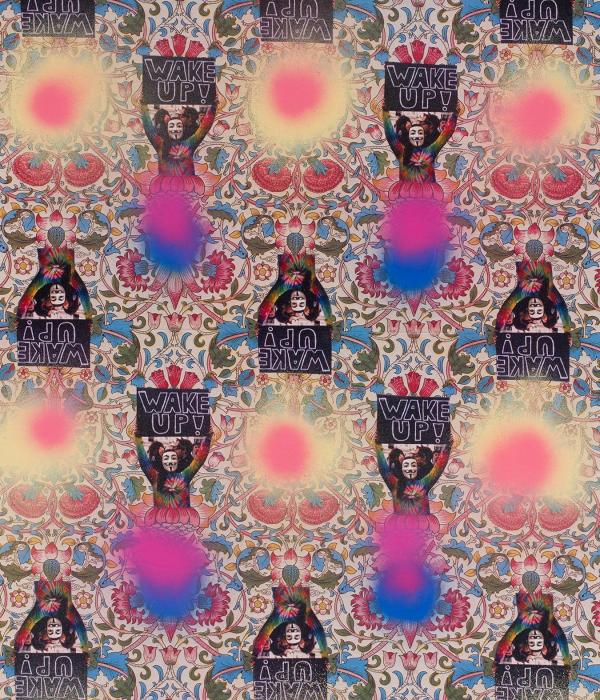

Many works in the exhibition are deeply connected to the digital landscape that is the flipside of contemporary tactility. Kate Just’s Feminist Fan series (2015–18) has an expansive life on instagram; Jemima Wyman trawls online sources for the protest photos that become her Propaganda Textiles (2016–17). Paul Yore, of course, practically downloads the internet into fabric. Gathering, translating and re-disseminating images via the digital, these artists emphasise the way that some boundaries are flattened while others—between countries, identities and ideologies—are reinforced.

This exhibition may not be dealing with ‘craftivism’ in the sense of craft as strategy for direct political action. For me, though, it beautifully articulates the possibilities for craft as an artistic strategy—as a survival mechanism—in the post-post-post-internet (I’m not sure where we’re up to), environmentally-collapsing, neo-Nazi-resurging, political-garbage-fire-burning, smartphone-addicted planet we currently inhabit.

It provides propositions for care (of self and others), for solace, and above all for paying attention; for sitting with it all—the ghost nets, the oil wells, the demonstrations, the rafts, the orange life jackets, the toxic masculinity, the endless scroll, the languages extinguished, the animals extinct, the 24hr news cycle, the whole Horrid Fucking Mess. Take it all in, it says. Breathe in and out. Don’t keep scrolling; don’t look away. One sequin at a time; one stitch, then another.

And another.

And another.

And another.

Craftivism: Dissident Objects and Subversive Forms is a Shepparton Art Museum curated exhibition touring nationally by NETS Victoria

[1] Anna Dunnill, ‘Paul Yore on the radical slowness of craft’, Art Guide, 2018, https://artguide.com.au/paul-yore-on-the-radical-slowness-of-craft, accessed 13 December 18.

[2] https://knitting-nannas.com/what.php, accessed 13 December 18.

[3] Anna Briers, ‘Subversive Craft as a Contemporary Art Strategy: Rethinking the Histories of Gender and Representation’, Craftivism: Dissident Objects + Subversive Forms exhibition catalogue, Shepparton Art Museum, 2018.

[4] https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2017/08/03/pilliga-protest-the-moment-200-farmers-and-nannas-tell-santos-t_a_23062445/, accessed 13 December 18.

_1-itok=jKHAdv6o.jpg)