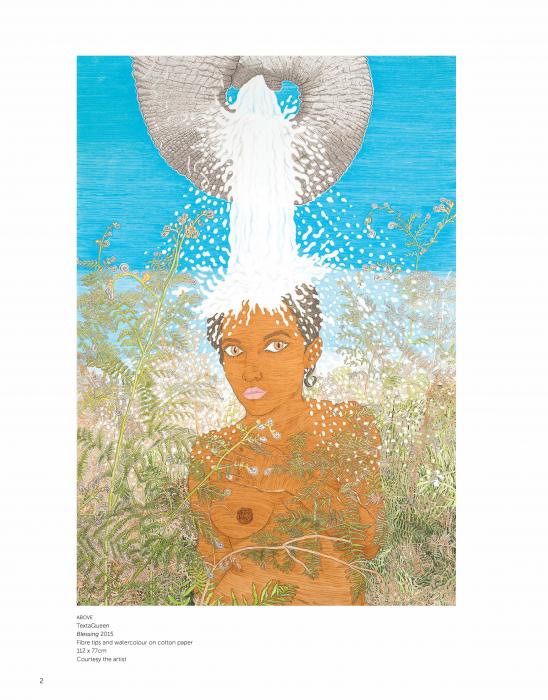

Those Monuments Don't Know Us

By Andy Butler

It’s been a strange time to watch arts institutions grapple with discussions about race, and the stark realities of anti-Blackness and systemic violence against First Nations people that have entered the public consciousness through the Black Lives Matter movement. There has been a wave of public awakenings from white people for whom discussions of racial justice seem very new. This is important in many ways, but the quick attempt to catch up now in the midst of a global uprising around BLM has been revelatory about just how far behind many of us are in thinking deeply about the dynamics of racialized power and colonialism that are at the foundation of all we do.

Over the past several years of finding a platform in these cultural spaces, it has become exceedingly clear just how poorly equipped these institutions are to grapple with their legacies of colonisation and structural racism, and the ways this history flows into the present. At their foundation, many of these big cultural institutions are living memorials to a Eurocentric world view, from their historiography, collections, staff, infrastructure—they are relics of a time before the White Australia policy was repealed. It is no surprise then that many are struggling to make sense of a push for racial justice.

The Art Gallery of New South Wales, along with a plethora of other arts institutions, recently posted black squares on their Instagram, in solidarity with the unrest going on internationally and closer to home.

A few posts earlier in the grid, in the days leading up to #blackouttuesday, AGNSW announced their reopening—with director Michael Brand earnestly inviting people back to the gallery, standing in front of an artwork that Brand says “sums up the challenges and possibilities of the moment we’ve all been through”, one that speaks to a vision of caring, one that speaks to the challenges and joys of connection in new life. [1] Brand earnestly makes links between the spirit of openness and togetherness of the AGNSW that he sees as represented in the painting. Dana Schutz’s bright self-portrait of her breastfeeding her child is a work that will invite audiences back to the gallery.

You’d be hard pressed to find a more contentious artist to represent the spirit of your institution at a time where we’re all talking about violence against Black people. Schutz—a white female painter—made headlines with another work at the Whitney in New York, Open Casket, a painting of lynching victim Emmet Till. Schutz says she was trying to memorialise Till’s death, many Black people pointed to issues around the cultural appropriation of Black suffering, the consumption and spectacle of Black death within white institutions. [2]

This isn’t to say that institutions shouldn’t be all acting to make significant changes, to dismantle the structures of power that have got us here, and that we are implicated in. It’s just that these spaces feel like they don’t excel at fostering deep and transformative discussions about racialized power.

Our arts ecology is built on a history of colonialism, looting, racism, violence, a cult of Eurocentrism. A past that flows into the present, that is at the foundation of the various appendages of the arts ecology. It’s the history, the worldview, the values, the lens through which these spaces make sense of the world.

The platforms provided to Black, Indigenous and PoC artists in these spaces can sometimes flatten the complexities and nuances of the ideas that emanate from their work. That is, there is vital art being made to help us make sense of where we are, but the cultural institutions that transmit this work to a public aren’t able to step up to the level of dialogue we need. Work from artists form these backgrounds is consistently reduced to just being about ‘identity’, as if ‘identity’ exists free of the force of politics and history that continues to determine how we all move through the world — it also consistently flattens the ways that structures of white supremacy affect people very differently.

While unpacking these problems shouldn’t take away from the sort of direct action that is required in the Black Lives Matter movement — and it has become clear from the past few weeks that the fastest way to make change is an uprising — thinking about how the work of non-white artists exists in the arts and cultural sphere does elaborate on the ways that nominally progressive and predominantly white audiences think about race, and structures of power and inadequate concepts built around it.

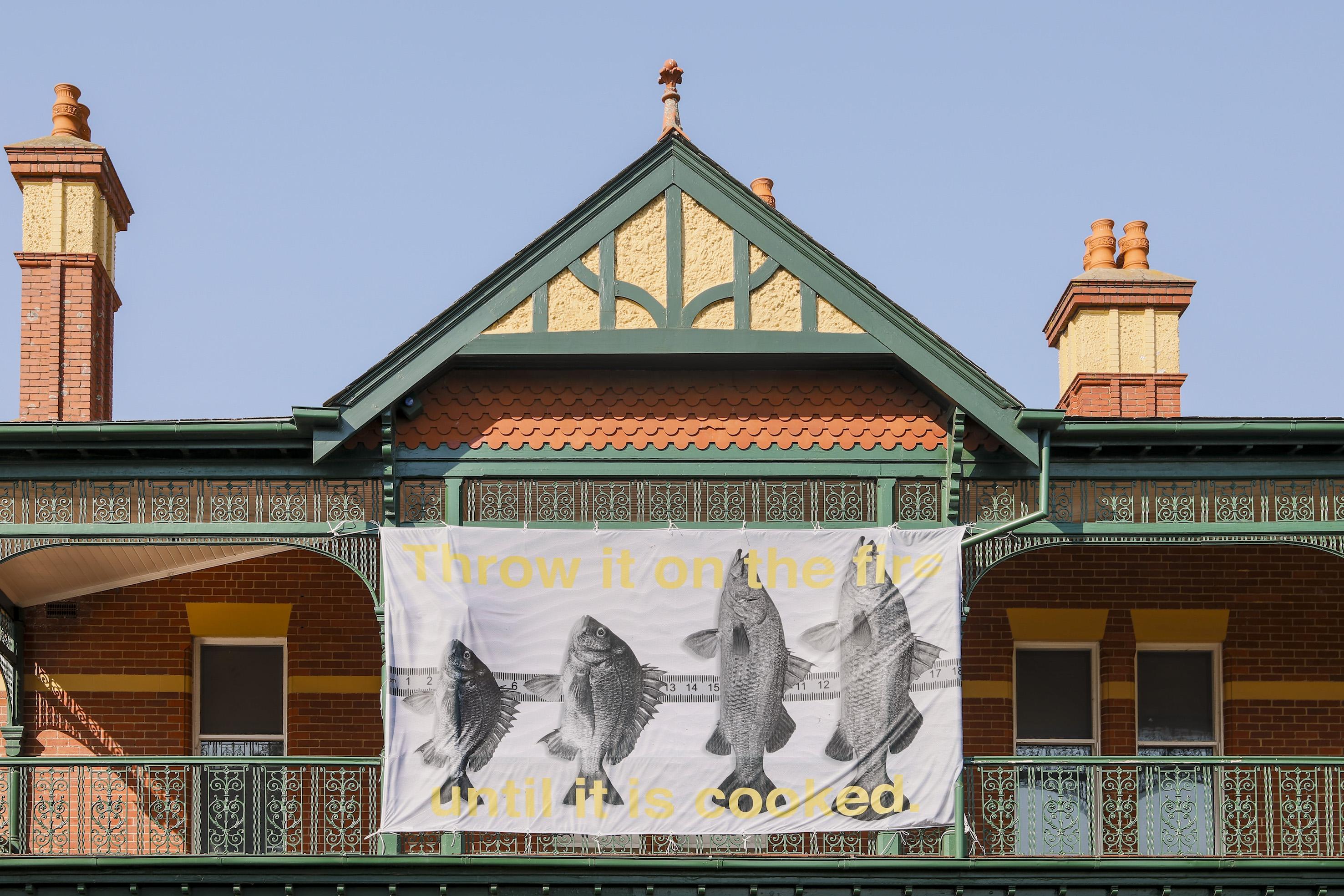

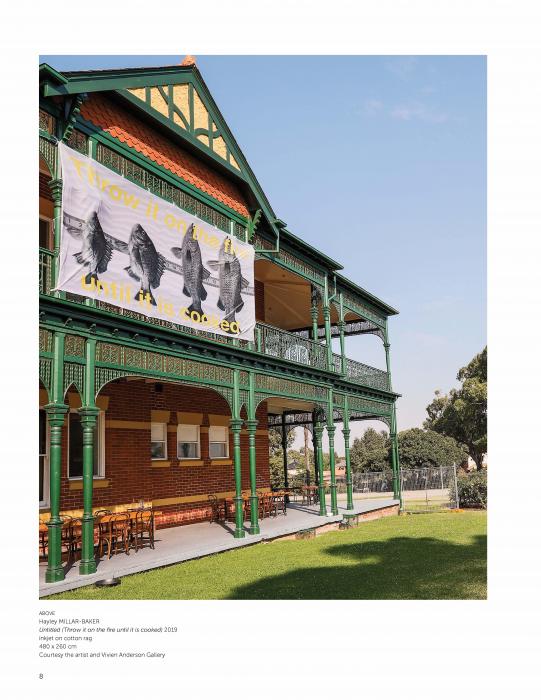

Last year I curated an exhibition called Those Monuments Don’t Know Us in a historic building called Bundoora Homestead Art Centre. [3] It is interesting as a contemporary art space insofar as it can’t hide how much it reeks of white supremacy and the ongoing colonial project. The Homestead is a Queen-Anne style mansion built in 1900 on Wurundjeri country by a British horse racing family. It is a living reminder and memorial of sorts to a dark past that is still here. It is a space where the historical and political links between Australian artistic culture and legacies of white supremacy are collapsed. When you’re not trying to hide the political contexts and structures that we’re working in, it’s easier to have conversations about a future where they’re dismantled.

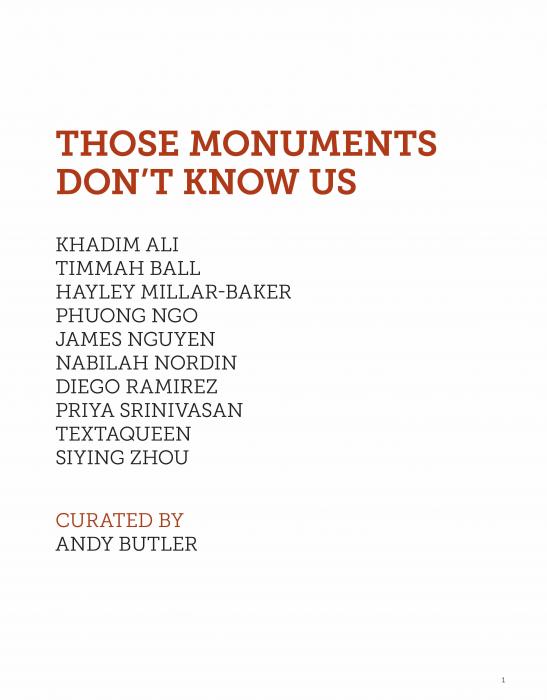

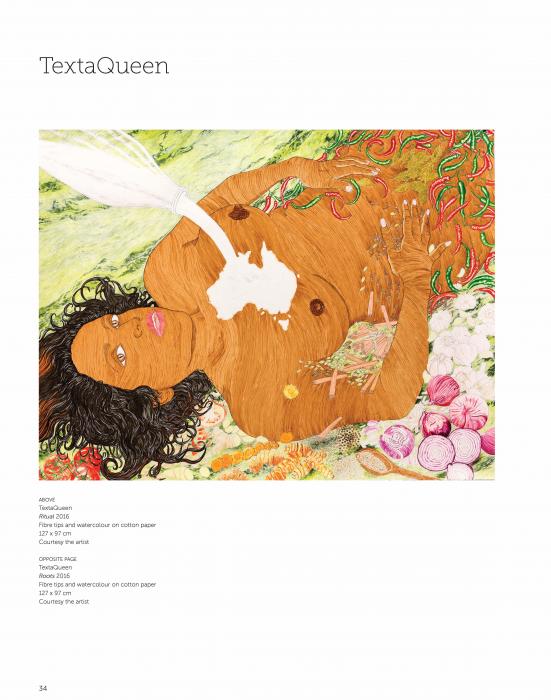

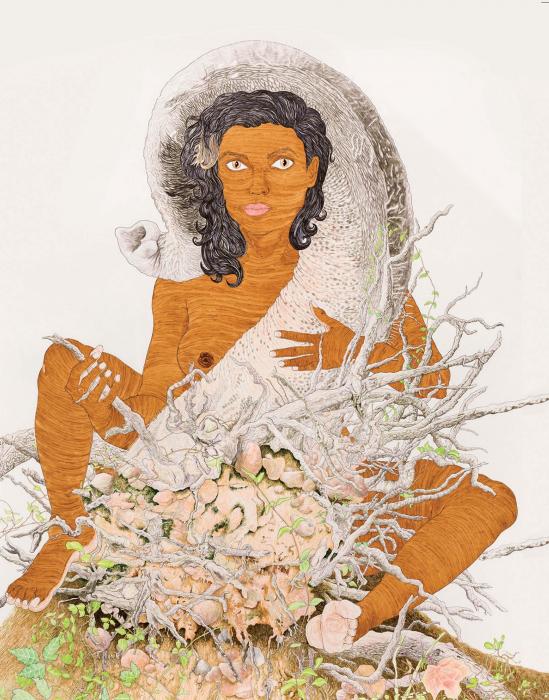

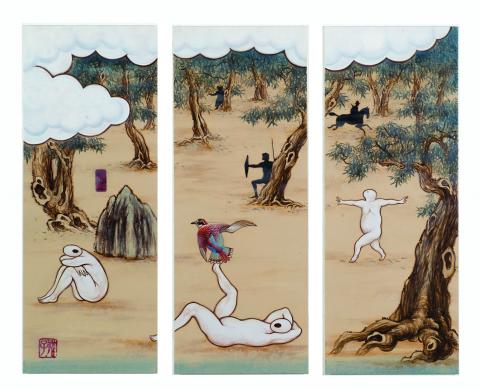

The discussions from non-Bla(c)k PoC that have come to the surface recently reminded me of much of TextaQueen’s work over the past decade. Texta’s work was the impetus for some of the broader ideas that brought together Those Monument’s Don’t Know Us – especially around what Texta describes as ‘complicated forms of empowerment’ of ‘marginalised’ identities.

Since at least Texta’s series Unknown Artist from 2012, they have been considering what it means to make sense of a migrant Indian heritage that is parsed through a white lens. How to connect to a heritage that feels distant, how to make sense of how we navigate the existing on the stolen lands of others as brown migrants from colonised countries.

In the Monuments exhibition, several works were included from their 2015 Rise and Fall series, including “Ritual” and “Bless”, both very explicitly considering the connection between Texta, whiteness, and their life on Wurundjeri country. In a building like Bundoora Homestead, and alongside the works from other artists, this becomes much more than an investigation of cultural heritage or identity, and more a consideration of what it means to navigate structures of a white supremacist history. The forms of ‘empowerment’ that are offered to non-Black PoC are usually founded on a capacity to gravitate closer to white values, to embody a “model minority” narrative, to contort ourselves so that we can be uplifted within a Eurocentric lens. Texta’s work, especially apparent in their 2018 God’s Save the Queen series, acutely draws out the tensions in trying to fight racism and empower marginalised voices through the systems of colonial oppression that lead us here.

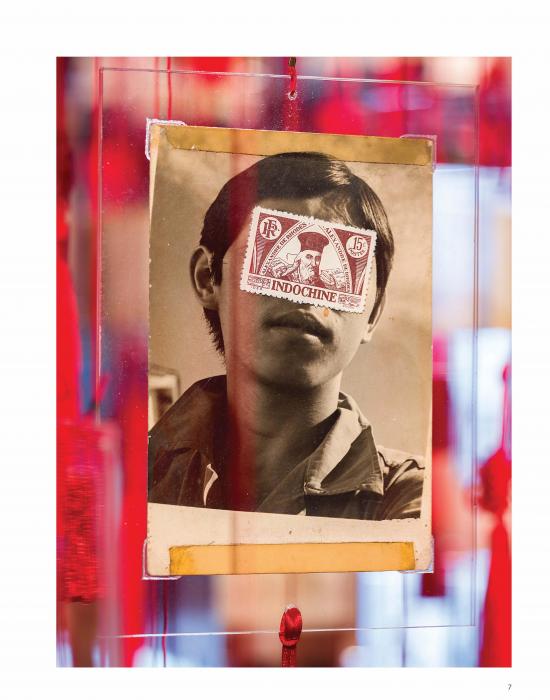

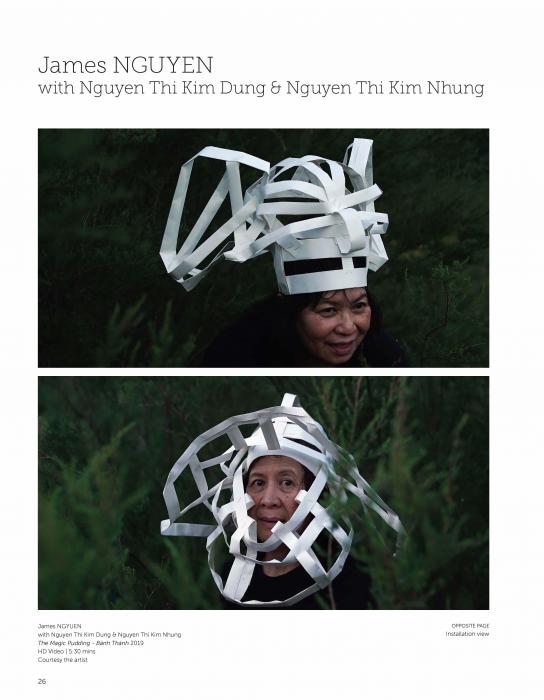

James Nguyen’s Magic Pudding – Bhan Thanh, made with his mother and aunty Nguyễn Thị Kim Dung and Nguyễn Thị Kim Nhung, similarly considers what happens when migrant histories meet white Australian culture. Made in the year of the 100th anniversary of Norman Lindsay’s The Magic Pudding¸ Nguyen works with his family to write a short adaptation of the work to perform in Vietnamese. They take the opportunity of performing the work to speak back to the racist and colonial undertones of the Norman Lindsay’s book, and draw parallels between the colonial histories of Australia and Vietnam.

The tension in the work is that the three performers make their own costumes to perform the roles of anthropomorphic characters who act out a play that mirrors the colonial project in Australia – stealing resources in the form of a never-ending pudding, fighting anyone who gets in their way. Nguyen’s work, including his Portion 53 shown in The National 2019, considers how one navigates a history of dispossession in their country of origin, only to be swept up in another ongoing colonial project.

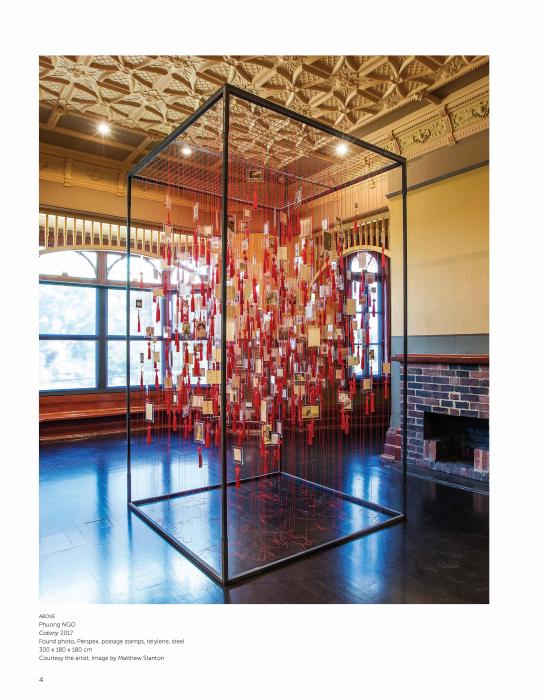

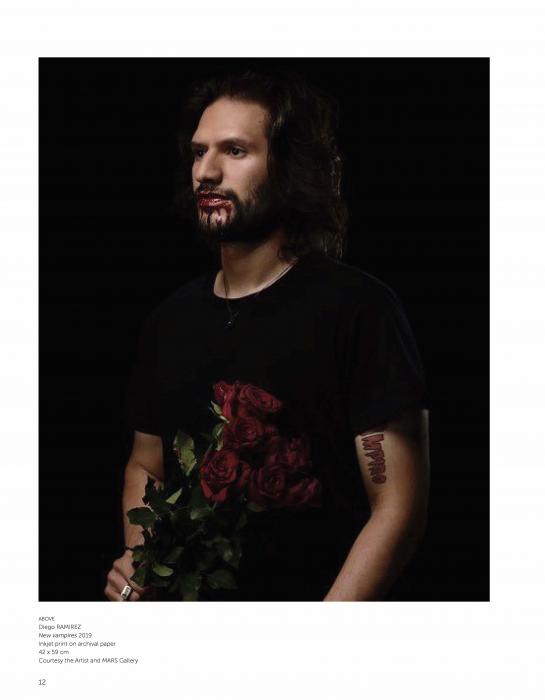

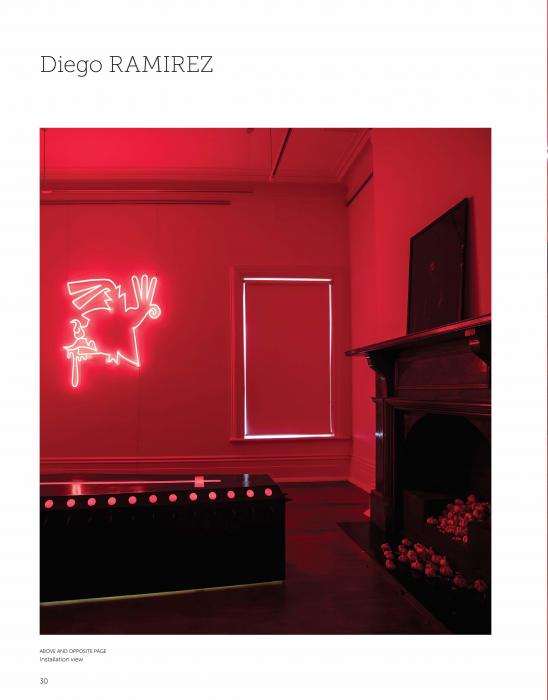

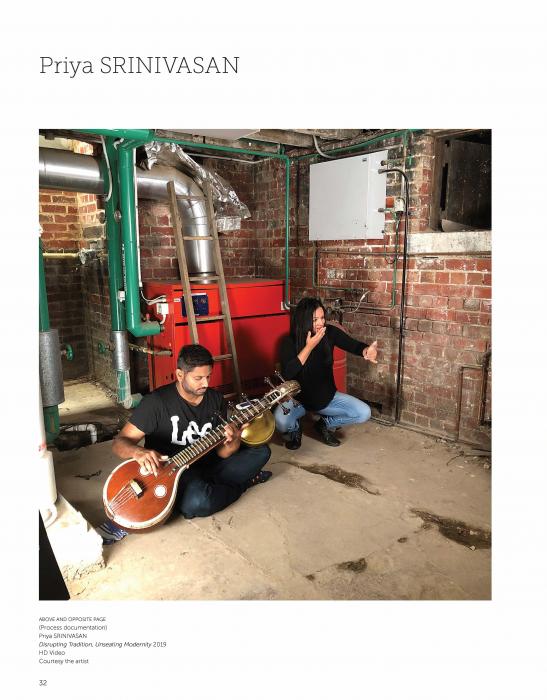

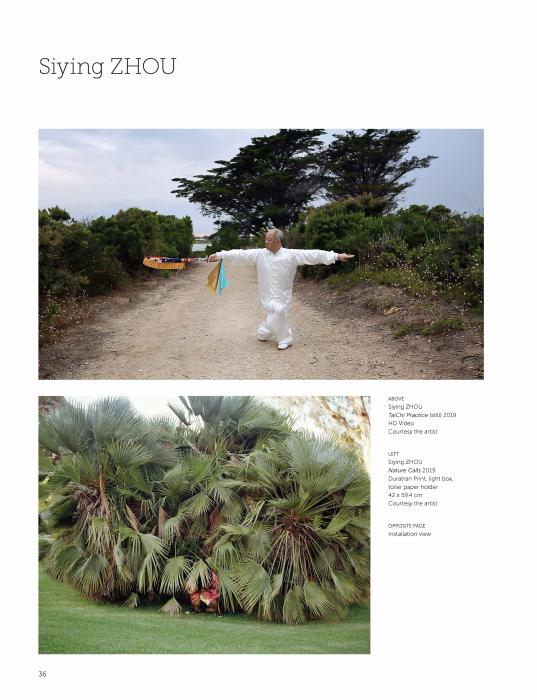

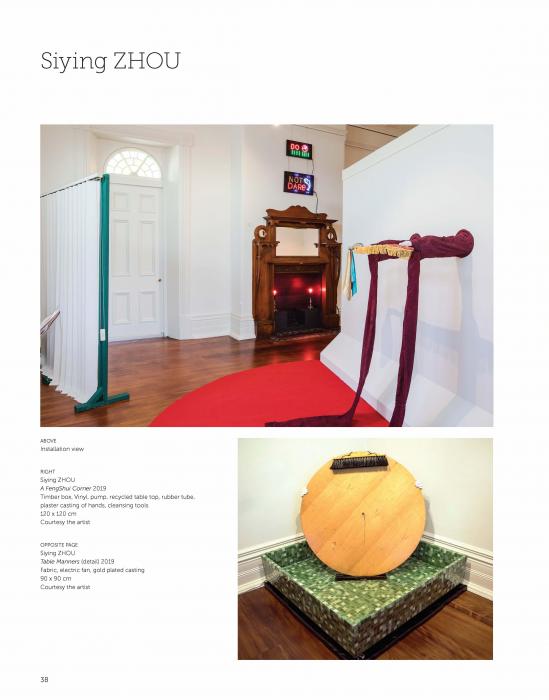

These sorts of ideas and discussions of how we are implicated in the colonial project even though we can feel the blunt force of whiteness permeates many of the other works in the exhibition. Siying Zhou’s We Are Here for Your Happiness used Chinese restaurants in Australia to consider how Chinese culture here has morphed into something all its own according to Western tastes, Diego Ramirez’s Monument to the Night recreated a Vampire’s lair in one of the rooms – as if to be drawn into the colonial project here to be turned into an undead monster, Priya Srinivasan’s Disrupting Tradition, Unseating Modernity, involves her performing a style of classical Indian dance, Bharatanatyam, that makes claims to a thousand year history but is a creation of the British colonisers in India.

Together, the works spoke to different ways that the artists navigate the racialised structures of power that flow from our country’s past into our present. What became clear from the exhibition though, and in the discussions that were had with the artists in trying to making sense of Australia, is that histories of white supremacy affect people differently, its demands on us are different dependent on race, gender, class — even if we’re all non-white.

We need to push back against the flattening of these differences, the obscuring of how many of us experience these structures of power, of how some of us become implicated in them and of how the promise of empowerment and uplift within these systems of power is often dependant on playing into tropes and ideas that will never, also, be able to dismantle them. If we’re clearer on the ways that mainstream arts and culture in Australia is still a living memorial to Eurocentrism, then we can be more clear-eyed on whether the work we’re doing as non-Black PoC is working against the structures of racialized power or just helping to perpetuate them.

[1] See the Instagram post of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, on June 01,2020:

‘Welcome back to the Gallery!

Today we open the Gallery doors to the world for the first time in ten weeks. Our director Michael Brand welcomes you back to our home on Gadigal Land with this special message inspired by an utterly dynamic painting filled with human energy, ‘Breastfeeding’ 2015 by the artist Dana Schutz. We're pleased to report that the Gallery today is also filled with human energy, as visitors return and recharge in the presence of in-real-life art. It is a joy to be able to reconnect, so we hope to see you at the Gallery soon or join us online at the new #TogetherInArt website.

Please see our website for more information about visiting the Gallery including free timed ticketing and the measures we’re implementing in line with NSW Government’s health guidelines to keep visitors safe during COVID-19.

Artwork: Dana Schutz, 'Breastfeeding' 2015, Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the 2015 USA Foundation Tour and the Mollie and Jim Gowing Bequest Fund. © Dana Schutz’

With thanks to Presenting Partner of the Art Gallery of New South Wales Contemporary Galleries @ubsglobalart ’ https://www.instagram.com/tv/CA4F6Xkjech/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link, last accessed 26 June 2020.

[2] See Calvin Tomkins, ‘Why Dana Schutz Painted Emmett Till’, The New Yorker, April 3, 2017

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/10/why-dana-schutz-painted-emmett-till

[3] Andy Butler, Those Monuments Don’t Know Us, March 9, 2019 - May 5, 2019, Bundoora Homestead Art Centre, https://www.bundoorahomestead.com/exhibition/those-monuments-dont-know-us/

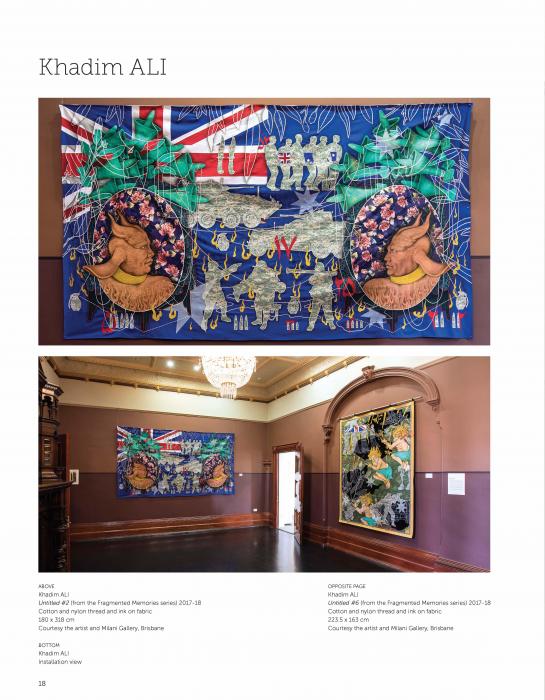

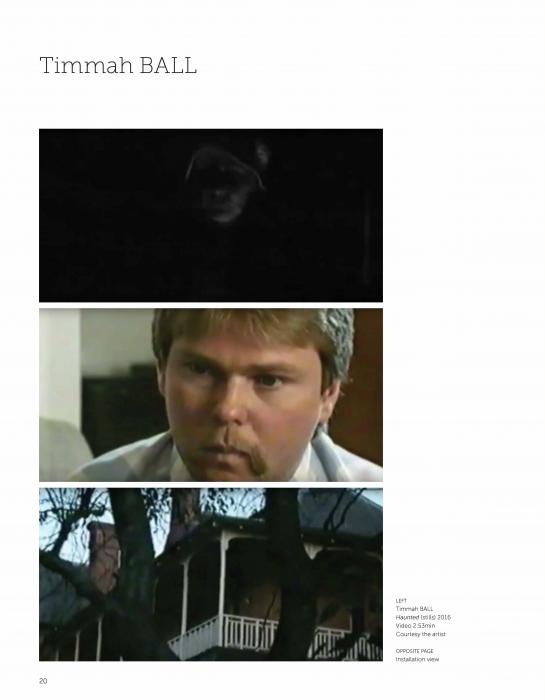

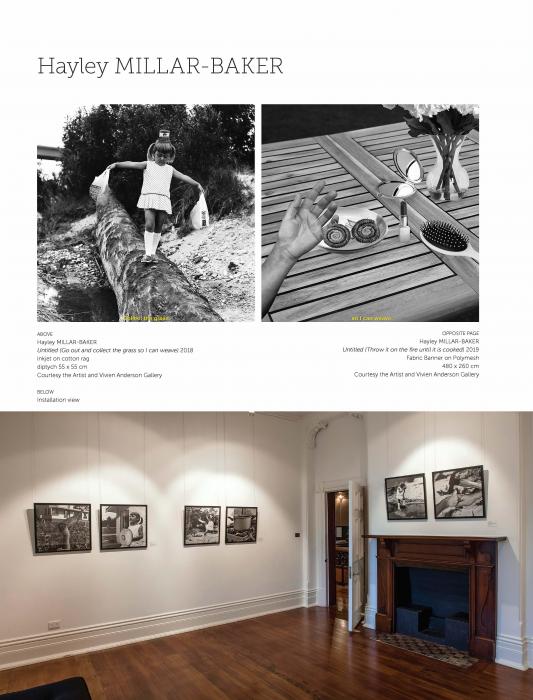

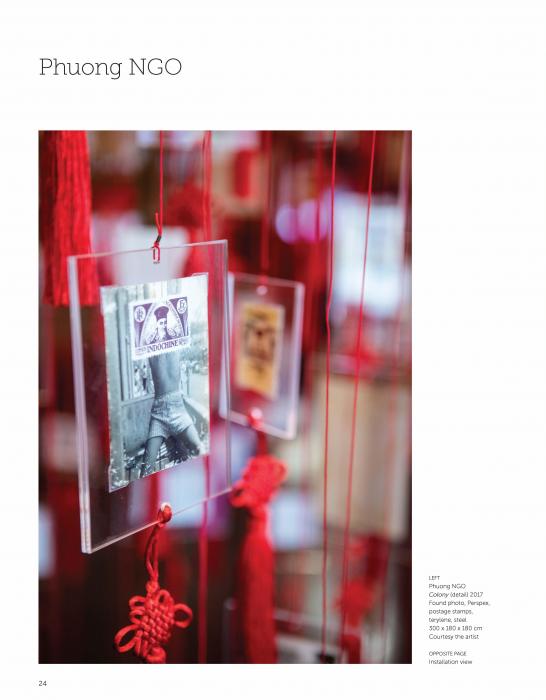

The slider below contains the full catalogue of the exhibition Those Monuments Don’t Know Us, 2019, courtesy of Bundoora Homestead Art Centre and Andy Butler.

(please zoom in to see the images and text in the slider)

,%20fibre%20tips%20and%20watercolour%20on%20cotton%20paper,%20112%20x%2096%20cm%20(44%20%C3%97%2030%20in).jpg)