Protest Tautohetohe: Objects of Resistance, Persistence and Defiance

Text excerpt and images reprinted from the chapter 'Anti-Nuclear Protest' in Stephanie Gibson, Matariki Williams and Puawai Cairns, Protest Tautohetohe: Objects of Resistance, Persistence and Defiance,Te Papa Press, November 2019.

(with permission from Te Papa Press)

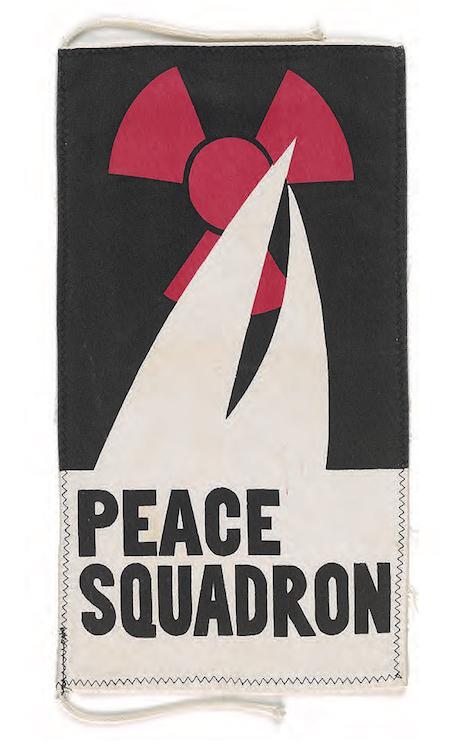

Port protests

This pennant at right, with its sails moving across the international radiation warning symbol, flew from the masts of the Peace Squadron, set up by Anglican minister the Reverend George Armstrong in October 1975 to meet all nuclear-powered and/or-armed warships visiting New Zealand ports. Squadrons in Auckland, Wellington and Lyttelton featured all manner of seagoing vessels – powerboats, sailboats, dinghies, canoes, kayaks and surf sailers. Many dramatic scenes played out in harbours around New Zealand until the Labour government banned all visits by nuclear vessels in 1984.

Armstrong recalled that ‘bobbing around on the ocean you’ve got a lot of opportunities’ for protest action.[1] Even though there were risks in getting too close to the huge naval vessels, Armstrong said he was never as scared as he was during the Springbok tour protests in 1981.

Artist Pat Hanly painted several ‘No Nuclear Ships’ banners in his back garden like the one overleaf; they flew from Peace Squadron masts during port visits by the United States Navy in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

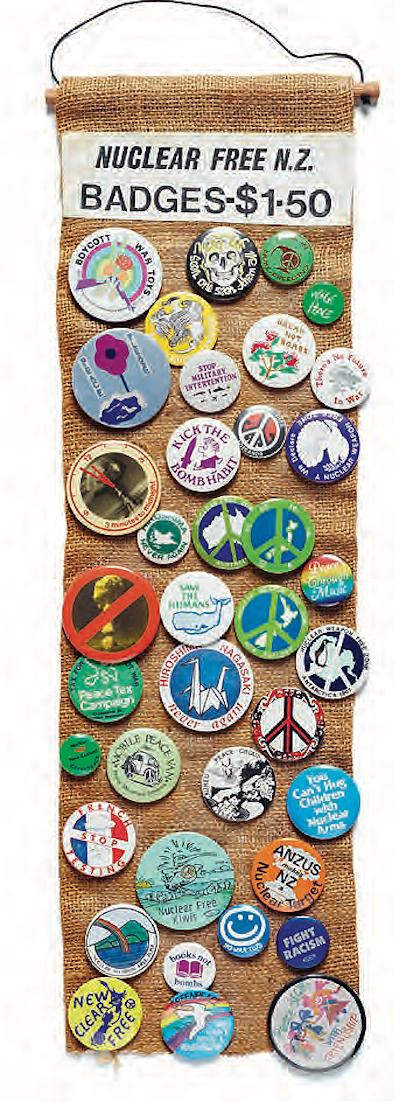

Peace badges

This strip of badges pinned to hessian shows how the New Zealand Peace Foundation sold protest and peace badges in New Zealand during the 1980s and 1990s. Thousands of such badges were made and shared by anti-nuclear and peace movements around the world.

Badges play an important role in protest culture – they are cheap to make, easy to distribute and sell, and wearable on any article of clothing. They are small enough to be relatively unthreatening, and can slip beyond dramatic protests into everyday life more easily than larger objects.

Badges transmit ideas and causes, and help people create their own protest identities. Their symbols and slogans can be powerful reminders of issues and concerns in society. When Ken Thomas gave his large collection of protest and peace badges to Te Papa, he felt that badges were the ‘best way to keep memory alive’.[2]

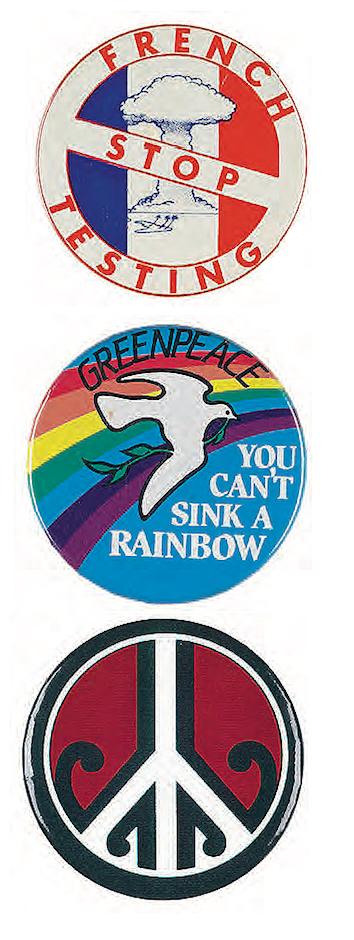

Design on peace

Greenpeace made the badge at top right to protest against French nuclear weapon testing. The image rewards close inspection: it combines the French flag, and its patriotic colours of blue, white and red, with a mushroom cloud blasting the palm trees of a Pacific atoll – usually an alluring holiday scene of paradise.

Although they are among the smallest of protest objects, badges can be powerful and effective in delivering good design and concise messaging. For example, ‘You can’t sink a rainbow’ (middle right) effectively combines a rainbow as a symbol of the anti-nuclear movement and the dove of peace with the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior, along with the impossible idea of actually sinking a rainbow.

Localised versions of the iconic Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament symbol were created, and in the design at the bottom right Gavin Patterson reinterpreted the peace symbol with miha fern fronds uncurling inside a CND symbol, symbolising hope and growth. It won him a national CND competition in 1985 for best design.

The badge at right suggests that New Zealand’s obligations as a member of the ANZUS treaty could bring the threat of nuclear catastrophe to its shores through visits by American nuclear- powered and/or -armed vessels.

The logo of the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement features on the badge below. The movement was formed in 1980 to widen the struggle against nuclear testing in the Pacific to include independence from colonial powers. As in many protest images at this time, the clichéd symbols of the Pacific (sun, sea, beach and palm trees) are repurposed to stand for what could be lost.

‘ANZUS makes NZ a Nuclear Target’ badge, early 1980s. Produced by the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone Committee. Gift of Anne Else, 2004. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH014499).

‘For a Nuclear-Free Pacific’ badge, 1980s. Produced by the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement. Gift of the Estate of Ron and Carmen Smith, 2015. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH024469).

'Boycott French Products' badge, 1985. Maker unknown. Gift of Mark Strange, 1989. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH003650/21).

'If it's safe' badge, 1980s. Maker unknown. Gift of Ken Thomas, 2008. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH011827).

'Nuclear Weapon Free Zone' badge, 1981. Designed by Lawrence Ross, New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone Committee. Gift of Ken Thomas, 2008. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH011812).

'We declare a nuclear weapon free zone' badge, 1982. Produced by Lawrence Ross, New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone Committee. Gift of the Estate of Ron and Carmen Smith, 2015. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH024475).

Badge (CND symbol), 1980s. Maker unknown. Gift of the Estate of Ron and Carmen Smith, 2015. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH024470).

'Keep New Zealand Nuclear Free' badge, 1990s. Produced by Lawrence Ross, New Zealand Nuclear-Free Peacemaking Association. Gift of Ken Thomas, 2008. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH011813).

'New Clear Free' badge, 1980s. Produced by the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone Committee. Gift of the Estate of Ron and Carmen Smith, 2015. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH024476).

'You can't cuddle children with nuclear arms!' badge, 1980s. Maker unknown. Gift of Anne Else, 2004. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH014497).

Badge (kiwi), 1980s. Maker unknown. Gift of Ken Thomas, 2008. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH011853).

'Remember Hiroshima Nagasaki' badge, 1980s. Manufactured by EYP Ltd. Gift of the Estate of Ron and Carmen Smith, 2015. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH024473).

'Nuclear Free Pacific' badge, 1980s. Manufactured by EYP Ltd. Gift of Anne Else, 2004. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH014498).

'Out of ANZUS' badge, early 1980s. Maker unknown. Gift of the Estate of Ron and Carmen Smith, 2015. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (GH024505).

Protest fashion

This dramatic outfit was successful in terms of both fashion and anti-nuclear protest. Lisa McEwan created La Bombe for the 1988 Benson & Hedges Fashion Design Awards, New Zealand’s premier fashion design event. It was highly commended in the ‘After Five’ section.

McEwan effectively channelled contemporary political and environmental concerns through a show-stopping and memorable garment. She combined the fashionable female silhouette of the late 1980s with an evocation of the terrible seductive beauty of a mushroom cloud sweeping up the body and acid rain diamantes falling down the tulle cape. McEwan recalls: ‘La Bombe, came out as the finale piece for the 1988 B&H Awards. The silhouette was of an atomic cloud, with black veiling used to give an air of mourning and foreboding, while diamantes signified acid rain … It was extremely well received by the audience … However, true to what I had been told, it was too extreme to win at the B&H.’ [3]

La Bombe channelled the anger many felt after the bombing of the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior in Auckland. It also celebrated the passing of the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act in 1987. McEwan recalls: ‘I had always been politically aware, being very involved in the Springbok tour protests and other human-rights campaigns of that era. By the time of the Rainbow Warrior bombing in 1985, I was a young parent, deeply concerned about the nuclear threat and incensed that a foreign power could inflict this act of terrorism in New Zealand waters. Many artists got behind the anti-nuclear movement in the following years, but I remember the Topp Twins being challenged as to whether singing a protest song could actually do anything to facilitate change. They simply replied that writing songs and performing was what they did, so they were going to use those skills and that platform to add weight to the campaign.’[4]

World Court Project quilt

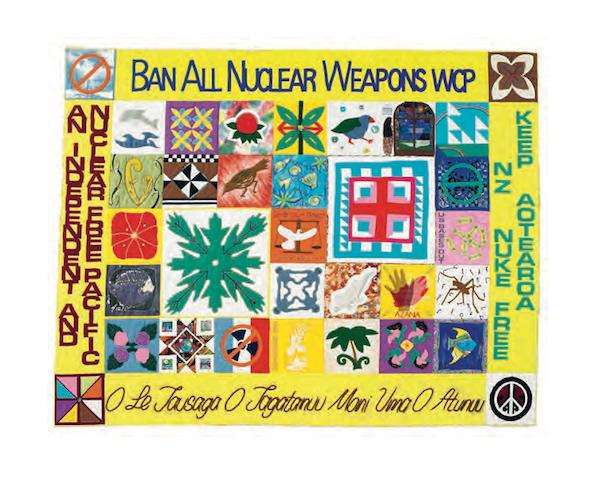

This protest quilt, designed by Joanne Bains for the World Court Project in 1994, calls for a ban on all nuclear weapons, and an ‘Independent and Nuclear Free Pacific’. The project was initiated by New Zealanders who took the issue of whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons was legal to the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion.

The panels depict a range of Pacific and New Zealand plants, animals and nuclear issues. The Rainbow Warrior is acknowledged top right. Other issues are included in the quilt, including apartheid, United States military bases, pollution and extinction. The two largest central blocks are tivaevae (patchwork and applique quilts) made by Cook Islands women in New Zealand. Secondary school art students also helped make some of the panels. The Sāmoan language inscription on the lower border translates as ‘International Year of World’s Indigenous People’, which had taken place the previous year.

The soft, tactile, colourful and visual qualities of quilts can make them non-threatening but effective protest objects, translatable across cultures. This quilt was toured nationally and internationally. Thousands of cards depicting it were sold to fundraise for the World Court Project. In October 1995 it was displayed at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, when New Zealand’s ‘Declarations of Public Conscience’ were presented.

On 8 July 1996, the International Court of Justice delivered its finding that the ‘threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law’.[5]

[1]. Reverend George Armstrong, interviewed by author Stephanie Gibson, 2007.

[2]. Ken Thomas, personal communication with author Stephanie Gibson, 30 October 2007.

[3]. Lisa McEwan, unpublished statement, 2011.

[4]. Lisa McEwan, unpublished statement, 2011.

[5]. International Court of Justice, 'Legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons', Advisory Opinion of 8 July 1996, www.icj-cij.org, accessed 13 October 2017.