Everywhen, elsewhere

In contemporary art writing and criticism, the recurring figure of the platform underscores themes of structural uncertainty and indeterminacy. The figure of the platform is also regularly put to work in contemporary art exhibitions, with their project-based initiatives, limited time-frames and borrowed spaces. In each instance this notion is designed to evoke the horizontal functionality of a provisional set-up made for a certain moment. But there is also the idea of a zone that is somewhat elevated, apart, and at a remove from things. The title of the exhibition Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia (Harvard Art Museums), curated by Yamatji-Inggardi curator Stephen Gilchrist, situates it as a visitation from somewhere else (Australia), yet also as an event that is now somewhere else again. Already the exhibition poses the question of the relation between the ‘eternal present’ of its title and the time of contemporary art. From the outset, it seems, then, to point to a strange new aesthetic and political terrain where the times and places of art have lost their bearings. What then is this field and where are its limits?

In his recent collection of essays titled In the Flow, Boris Groys writes that contemporary art is no longer concerned with the appeal to eternity that traverses medieval art, nor does it share the orientation toward the future that became a crucial element of modern art. In the same way, according to Groys, contemporary art dispenses with the modern notion that the presence of the present ‘can only be experienced at one moment.’(1) Groys claims that contemporary art leaves behind its traditional function of making art objects. Instead it ‘produces information about art events.’(2)The epoch of contemporaneity comes into its own with digital modes of reproduction and archiving and their unmatched capacity to synchronise disparate moments and histories under the sign of the contemporary. Contemporary art, Groys suggests, is most of all interested in its own conditions of contemporaneity. Yet what is also critical to this oddly circular conception of contemporaneity is, as he notes, its regime of real-time digital surveillance. The quasi-universal gaze of the internet – medium of contemporaneity par excellence – tracks every user, click, and look.

As an example of this digitally supported contemporaneity, Groys refers to the suturing of in situ action and online documentation in the case of Marina Abramovic’s performance The Artist is Present (2010). Abramovic would sit silently and look into the eyes of visitors who came, one by one, to sit at a table with her at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Groys takes the partial staging of Pussy Riot’s iconic Punk Prayer (2012) at the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow as another example of this digitalised contemporaneity. The crew who filmed – and archived – the performance were instrumental to the operation of the work as a contemporary artwork. Groys emphasises that the internet as digital medium is not part of the flow of time that defines contemporary artworks. On the contrary, its role is to bring about a stopping of the flow in order to manage and preserve the event as an artwork while also making episodes in the flow of time available. Analogously, museums today, like websites, serve as platforms that impose spatio-temporal limits on event-based projects in order to make them archivable and accessible. Olafur Eliasson’s iconic Weather Project (2003) at the Tate Modern in London could be seen in these terms as a perfect summation of art’s deepening investment in contemporaneity. Two million visitors visited the simulated outdoor weather conditions in the museum’s Turbine Hall and looked up to contemplate their reflections in the mirrored ceiling. The visitor-participants’ leisurely trajectories in the large interior space of the Turbine Hall embody the principle of flow. Even as the reflection in the Turbine Hall’s high ceiling –part of the installation design – reverses and upends the scene on ground-level, it attests to the fascination that this mode of artistic production has with its own contemporaneity. At the same time, the god’s-eye view of things recalls the sovereign gaze of surveillance. Yet Eliasson’s iconic event plays out a logic that is already operative in the space where it occurs. London’s Tate Modern – aptly enough, a repurposed power station located in the heart of what was once the world’s largest empire – is today the site par excellence of art’s global contemporaneity.

Groys links this dystopian account of contemporaneity to altering conceptions of temporality at different historical moments. Against the grain of most commentaries on the topic, his portrait of contemporary art foregrounds its formulaic qualities. We discover a ‘fluidised’ art hypothetically in sync with the temporal flow, yet perennially in search of validation in the shape of documentation, and thus ultimately captive to the mechanisms of surveillance and administration that shape contemporary life. Groys’s idea of past, present and future as source material for a contemporaneity that continually flips back and forth between flow and capture is compelling. His incisive characterisation of the logic of contemporary international art nonetheless leaves the question of recent forms of artistic production that brush up against this category of the contemporary without yet seeming to belong in it or to it.

Occupying three galleries on the third floor at Harvard Art Museums (formerly the site of the Fogg Art Museum), the small scale of Everywhen brings its guiding concepts into focus, at the same time conveying an understatedness seldom encountered in survey exhibitions of this kind.(3) In Gilchrist’s exhibition, contra Groys, the flow of time does not function as source material to be captured digitally or consigned to oblivion.(4) At least as it presents itself through intermediary concepts such as ‘remembrance,’ ‘transformation’ , ‘performance’ and ‘seasonality’, the exhibition’s time-frames remark time as a subjective and objective condition that is definitively elusive, yet also neverending and ineluctable, like a debt or a gift.

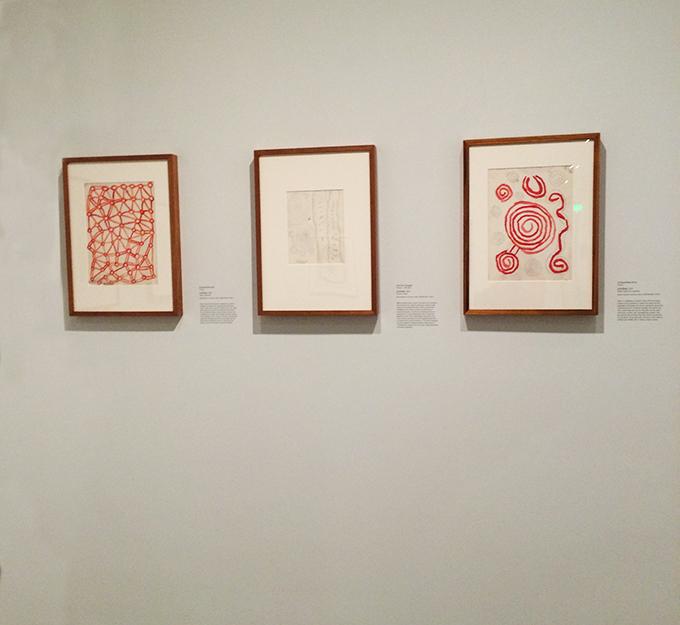

Near the entrance to the show a group of framed works on paper, all modestly-scaled and dating from 1971-1972, hang in a line. [figure 1] For some, their distinctive disposition of spirals, striations, lines, networks and circles may immediately call up traditions of Indigenous inscription in Australia. But here it is not a matter of the materials most often identified with Aboriginal art – natural pigments on bark, or acrylics on linen or canvas, for example. Nor is it a question of media that are unmistakably contemporary. Some works are drawings in pencil. Some, presenting translucent trails of orange, red, and yellow, are watercolors. These works on paper – not a series, but a collection of found notations arising from a singular historical moment – come from Papunya, the small community of Aboriginal people displaced from their territories in Australia’s Northern Territory, later to become renowned as the birthplace of Western Desert Painting. Two drawings are attributed to Pintupi artists Anatjarri Tjakamarra and Uta Uta Tjangala – unknown names outside the locality at the time when they were made. Three watercolors are untitled and assigned to ‘unidentified’ artists. The ostensibly poor (government-issued) materials used take nothing away from the casual, rhythmical precision that runs through each of these works.

These manifestly experimental exercises from the key years of 1971 and 1972 exemplify what Gilchrist calls the ‘radical newness’ of Papunya art. Each is more an improvisation than a finished product. Poised at the threshold of the emergence of Indigenous art as a cultural phenomenon in Australia in the 1970s and 1980s, they are not yet that thing now perhaps too easily labeled ‘Aboriginal Art’. Yet they prefigure what is to come.

The coinage ‘everywhen’ comes from the anthropologist William Stanner, writing in the 1950s. In Stanner’s usage, the word helps to clarify the underlying logic of the Dreaming narratives as they shape Indigenous conceptions of the world. The Dreaming ‘was, and is, everywhen’, Stanner wrote. The everywhen in this way signals a creative enfolding of past, present and future. In this exhibition, the concept fans out in many directions, each inflecting the implications of this plastic, poetic and constructive view of time in a different way. It may be argued that Stanner's characterisation of the Dreaming resembles the mythological framing of time and narrative in many other cultures – we could think, for example, of the epic poems of ancient Greece. What is also important, though, is that Gilchrist’s presentation of the Indigenous ‘everywhen’ hinges upon a delicate balance between subjective and objective apprehensions of time. In this sense Everywhen entails a subtle yet radical inflection of the conceptual framework of 1988’s Dreamings – and, to some extent, that of the later Aratjara (1993). It is no longer a matter of the lure of an arcane religion or cosmology, or of Westerners’ fantasies of forms of exotic spirituality. Particularly in this international – and extraterritorial – frame, the notion of the everywhen invites audiences to encounter the conceptual world of certain artworks while maintaining a sense of their difference and reserve. Analogously, one could recall Kant’s thinking of time as at once empirically real and transcendentally ideal. Time here acts as a form of experience that is mysterious yet real to all those who are subject to it.(5) In this way Gilchrist’s reworking of the ‘everywhen’ dramatises its uncanny and ungraspable character.

Taking up themes of repetition, difference and disjunction, the first half of Everywhen (with two sections, ‘Seasonality’ and ‘Transformation’) deals with time as an inescapable reality. The second half of the exhibition (‘Remembrance’ and ‘Performance’) turns to subjective views of time. ‘Performance’ concerns subjective processes of continuance and perpetuation; ‘Remembrance’ examines collisions between competing Aboriginal and colonialist conceptions of time, yet also the fragile interval between memory and forgetting.

Ecological rhythms of renewal and decay are the focus of the first section of the show, ‘Seasonality’.(6) Seasonality appears here in the form of the intricate, lace-like lineaments of the yam vine in Djirrirra Wunungmurra’s almost monochrome ochre-on-bark titled Yukuwa [figure 2]. It appears again in the ‘subtle transitions’ of the pinks, roses, whites, and yellows of Emily Kngwarray’s Angwelarr agnerr (1996).(7) In this epic painting, where diagonals and chromatic contrasts suggest an intense energy, these transitions seems tumultuous, even perilous [figure 3]. ‘Knowing how to live with the seasons is a matter of life and death’, Gilchrist comments with reference to Kngwarray’s evocation of her Alhalkere locality.(8) This presentation of seasonality might be read as a reflection on more general questions of global warming and environmental politics.

The second section of the exhibition, ‘Transformation,’ focuses on acts of translation undertaken by artists at Papunya and elsewhere when they took the radical step of remarking what had been ceremonial forms of painting for public spaces and new audiences, using new materials including acrylics, and linen or canvas. Ronnie Tjampitjimpa’s famous Two Women Dreaming (1990) throws the play of revelation and concealment that is at work in these acts of encryption, reinscription and transmission into high relief. Situated in the vicinity of Tjampitjimpa’s painting, coolamons (or baskets) borrowed from Harvard’s Peabody Museum (and other sources) and dating back to the turn of the twentieth century, provide a sobering counterpoint. The presence of these objects reanimates a sense of their aesthetic efficacy while highlighting their formal continuities with Western Desert acrylic painting and thus posing the question of their relation to art that is considered to be contemporary. Their presence, along with the inclusion of other objects borrowed from ethnographic collections, underscores the shortcomings of a purism, or an historical amnesia, of the contemporary. The exhibition in this way implicates itself in art history’s narratives.

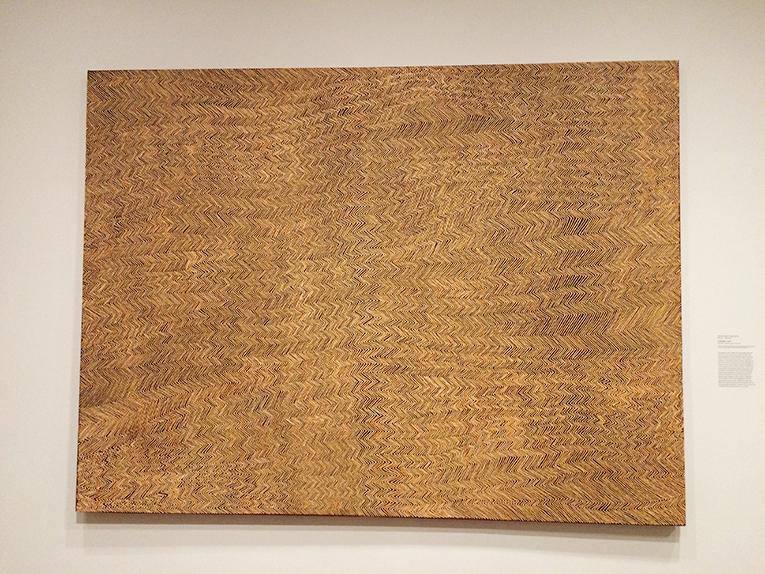

Subjective aspects of the apprehension of time and the intertwining of temporalities are themes taken up in the last two parts of the exhibition. Counter-intuitively, perhaps, the section of Everywhen titled ‘Performance’ is mostly taken up with paintings. The tiny dots in an untitled painting by the late Pintupi artist Doreen Reid Nakamarra do not just evoke the hazy endlessness of the Western Desert [figure 4]. The performance in this case surely consists in the patience that the painting demands. As Gilchrist notes, Nakamarra’s sublime painting entails an ‘intense repetition’, an active perpetuation of ‘ceremonial time’, as if conjuring the future into being.(9)

A more familiar contemporary form of performance has a part to play in ‘Remembrance’, the fourth section of the exhibition. In a photoseries commissioned by Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum titled We Bury Our Own, Christian Thompson reflects on photographs of Indigenous people from its archives in a paradoxical way. He photographs things, as well as himself, arrayed with fake votive paraphernalia: a garland, a model ship, a funerary veil, butterflies, a frame [figure 5]. In effect, Thompson imagines a new mourning ritual that rises above the expropriative precedents of empires – a tragicomic practice of ‘spiritual repatriation’, to use his phrase. Here acts of memory seem to pick up where acts of restitution fail. With its attention to trauma and the work of mourning in the wake of European colonization, ‘Remembrance’ provides a counterpoint to the more affirmative presentation of Indigenous engagements with other histories and traditions in the part of the exhibition titled ‘Transformation’. One artwork moves in another direction, however. Nyapanyapa Yunupingu’s screen-based digital animation Light Painting (2010-2011) hinges on the relation between drawing and the play of memory [figure 6]. A two-part installation combining acetate drawings on part with procedures of digital inscription, Light Painting lingers on the ellipses that ineluctably interfere with systems of marking time. In a mesmerizing sequence, a screen displays more than a hundred digitized white-on-blue acetate drawings, figurative and non-figurative, imperceptibly disappearing into one another. The drawings – the raw material for the animation – are presented in a grid configuration on an adjacent wall. According to the wall text next to the installation, Yunupingu’s work ‘has jokingly been referred to as mayilimiriw (meaningless) within the community where it is created.’ Yet here, precisely because it gives its audience so little to hold onto, the hiatus between the drawings and the animation turns into a lyrical meditation on time’s ungraspability. In a way Yunupingu’s Light Painting distills the logic of time at the heart of Everywhen. (Interestingly, in this case the digital appears to reverse the operation of digital imaging in Groys’s account of art’s contemporaneity. Here, in effect, it fails to stop or hold back the passage of time.)

Whether in the shape of Yunupingu’s exercises in translation across media or the laconic works on paper made at Papunya in the early 1970s, drawing is pivotal all through this exhibition. If drawing is a gesture that opens a form, Everywhen, too, behaves like a drawing. It presents a way of seeing certain works of Aboriginal art that fully assumes its debt to the thinking of time and becoming that Stanner called the ‘everywhen’. The image of time that the exhibition supposes, implying a layering and quasi-simultaneity of past, present and future, correlates with a logic that is already at work in many of the works shown. From this perspective, the violent incursion of a naïve temporality of conquest in the name of historical progress is not just palpable but painfully present. The exhibition in this sense accents the violent asymmetry of perspectives between apprehensions of time and space premised of storage, capture, and retrieval and those that start from notions of time and space as always in some way extraterrritorial or strange. Proposing an untimely contemporaneity made from enigmatic passages across temporalities, Everywhen perhaps imagines a way out of the currently ascendant shape of contemporaneity described by Groys.

It should not be forgotten that in the widely circulated year-by-year history Art Since 1900 (2004), authored by Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, and others, Aboriginal art is consigned to a forlorn text-box marooned in a commentary about the year 1989. Foster locates so-called ‘Dreamtime art’ between the poles of ‘“archaism” and “assimilation” in contemporary global culture’.(10) It is also interesting to think of the distinctive use of materials and media that characterise many of the artworks in Everywhen – notably, the attention it gives to the improbable uptake of acrylic painting on linen in communities like Papunya in the 1970s – in proximity to Rosalind Krauss’s influential description of the presumptively ‘post-medium condition’ of contemporary art, precisely to see how the exhibition flies in the face of her historicist account.(11) Closer to home and in a different vein, Australian curator and art historian Charles Green has sought to discount ‘spiritual’ readings of Western Desert art in the name of an overarching postmodernism. Green argues that the iconic works made in the Western Desert in 1971-1972 emerged from a two-fold engagement with land rights and specific problems in art practices in the early 1970s. These artworks are, Green argues, emphatically of their time.(12) From a different standpoint again, in the account of contemporary art proposed by Terry Smith, Aboriginal art is aligned with post-colonial art, and post-colonial art, in turn, sits alongside retro-modernism, sensationalism, and relational art, all of which are understood as parallel tendencies constituting contemporary art as a global phenomenon.(13) What is interesting here is how radically the ‘everywhen’ of Gilchrist’s exhibition eludes these categorizations with its deployment of a new conception of Indigenous art that recurrently moves between the singular and the universal. Gilchrist’s ‘everywhen’ brings poetry into communication with conceptual art and vice versa. It paradoxically highlights new modes of mythic utterance. Anachronistically or otherwise, it attests to singular alignments of subjectivity vis-à-vis duration in painting. Everywhen’s extraterritoriality has to do with how it escapes what are by now relatively familiar framings of Aboriginal art vis-à-vis contemporary art, particularly through the differential understanding of the excess of time that informs its presentation. The point is not simply to assert the contemporaneity of Indigenous art, but to show how it might alter our notions of what contemporaneity is.

How, finally, does this notion of the everywhen, and the artworks that bear witness to it, communicate with questions of territory and displacement? And what is an exhibition like this doing in the privileged locale of Harvard University? Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a long way from Papunya, Brisbane, or Bedford Downs. Extraterritoriality perhaps operates in two ways here. One has to do with Harvard University’s degree of extraterritoriality with regard to American life and in an international frame. Its founding in 1636 precedes that of the United States as an independent and sovereign state – and the British occupation of Indigenous lands – by a long margin. Its academic prestige likewise situates it as a cosmopolitan institution whose establishment precedes any assertion of national sovereignty. In practical terms, it also functions as a king-making instrument that is paradigmatically global in reach. As is regularly noted, Harvard’s vast endowment is comparable to the gross domestic product of national economies outside the United States, somewhere in the middle of the global scale. If there is a political force in this real-time, real-world recognition – artistic and political – between the art of Indigenous people in Australia and the quasi-sovereign world of Harvard, perhaps it stems from the disjunctive singularity of this liaison of real and still problematic or unacknowledged forms of authority and sovereignty. When I visited, I was struck by a placard inscribed with the word ‘Trump’, posted on a window across the road from Renzo Piano’s elegantly refashioned art museum complex. The sign was an oddity in the serene, low-key milieu of Prescott Street, Cambridge. Yet in a way it was also an indicator of the great oddity, for all its posture of understatedness, of that milieu [figure 7]. In this outward-looking sense, the event of Everywhen seems closer in character to other more overtly political events in the history of Aboriginal politics – for example, the radically interruptive appearance of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy outside Parliament House, Canberra, in 1972 – than to comparable exhibitions of Aboriginal art in other locations. As with the Tent Embassy, the asymmetry between one political voice and another – and their improbable face-off – is not incidental to the structure of the encounter.(14) There is even a certain poetic justice in the exhibition’s location. In this unlikely location, Everywhen stands in for a sovereign or quasi-sovereign presence that – as it also shows us – is radically missing.

Another way that the uncanny force of extraterritoriality makes itself felt in this exhibition lies in its attention to the multiplication of time-images. Everywhen’s time-images mark their difference from the prevailing logic of contemporaneity in part through their ‘radical newness’ (to recall Gilchrist’s description) and their appeal to the ungraspable gift of time as a liminal form that remains even in the wake of ‘territory’, in a situation of catastrophe, exclusion, and loss. Everywhen invites its visitors to share in this sense of the ultimate contingency of conditions of space, territory, and even time. As the unnamed narrator remembers in another story of platforms and time-zones, Chris Marker’s film La Jetée (1962): ‘This was the aim of the experiments: to send emissaries into Time, to summon the Past and Future to the aid of the Present.’

(1) Boris Groys, In the Flow, Verso, London, 2016, p. 142.

(2) In the Flow, p. 4.

(3) Everywhen ran from 5 February to 18 September, 2016. My account of the exhibition here draws in part on a forthcoming review for caa.reviews. I would like to thank Eddie Vazquez for his comments on an earlier draft and staff at caa.reviews for their permission to draw on parts of the text of the review in this essay.

(4) Harvard Art Museum’s website for Everywhen situates it as a survey of ‘contemporary Indigenous art from Australia’ even if much of the work in the exhibition does not self-evidently fit this description. (See http://www.harvardartmuseums.org/visit/exhibitions/4983/everywhen-the-et... ). The exhibition catalogue uses the phrase ‘the eternal present’ rather than the word ‘contemporary’. Yet here Gilchrist also writes that museums must reactivate connections with Indigenous peoples and transform the archive by ‘transporting it into the realm of contemporary art’ (Stephen Gilchrist, ed., Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Australian Art from Australia, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2016, p. 23). This is almost a reversal of the relation between the archive and the logic of contemporaneity outlined by Groys.

(5) For historical analogies between Indigenous conceptual systems and those of Europeans, including Kantian philosophy, see Fred Myers, ‘Doublings’, in Gilchrist, Everywhen, p. 53.

(6) This account follows roughly the path suggested to me by the installation of the exhibition at Harvard. The catalogue adopts a different sequence, beginning with ‘Transformation’, followed by ‘Performance’, ‘Seasonality’, and finally ‘Remembrance’.

(7) Gilchrist, Everywhen, p. 26.

(8) Gilchrist, p. 26.

(9) Gilchrist, pp. 24-5.

(10) Hal Foster, ‘Aboriginal art’, in Hal Foster , Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, and David Joselit, Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism, vol. 2, Thames and Hudson, New York, 2004, 662.

(11) See, in particular, Rosalind Krauss, ‘”A Voyage on the North Sea”: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition’, Thames and Hudson, London, 2000.

(12) See Charles Green, ‘The discursive field: Home is where the heart is’, in Fieldwork: Australian Art 1968-2002, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2002, and Ian McLean, ‘Aboriginal art and the artworld’, in McLean (ed.) How Aborigines Invented the Idea of Contemporary Art, IMA/Power Publications, Brisbane, 2011, 67-68.

(13) See, for example, Terry Smith, What is Contemporary Art, Chicago University Press, Chicago, 2009, in particular Parts II and III.

(14) On this, see, for example, Oliver Feltham, ‘Singularity happening in politics: the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Canberra 1972’, Communication and Cognition, vol. 37, no. 1, 2004, 225-245.