The State of Painting

It was a rare treat to see three contemporary (mainly Australian) painting exhibitions in the space of a week in Melbourne and Geelong with the closing stages of 2016: Painting. More Painting at ACCA, the NGV International’s Shut up and paint and the Geelong Contemporary Art Prize (GCAP) 2016.

Works by Jenny Watson, Karen Black, Juan Davila, Louise Hearman, Ry David Bradley, Moya McKenna and Angela Brennan were included in both Melbourne shows while David Jolly, John Nixon and Huseyin Sami were also in those as well as the GCAP 2016 (which was won by Kate Beynon) selected from the 30 finalists.

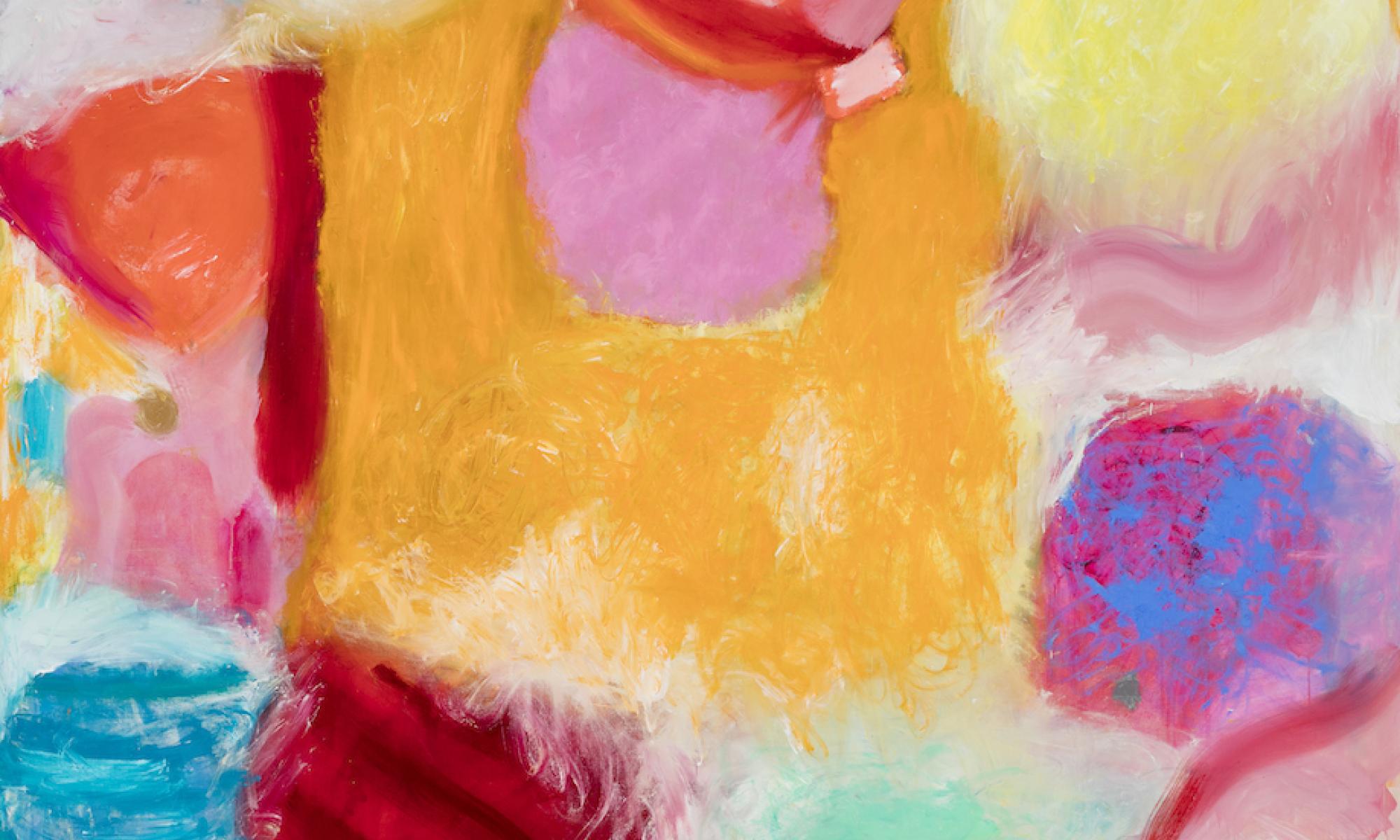

The Melbourne-based painter Angela Brennan wrote in an email to Jan Bryant in 2016 for her Painting. More Painting catalogue interview/essay:

There is inbuilt architecture to the painting. Anything can happen if you are plugged into this. But you only get to that state when you are immersed, engaged and right into it. That’s when the paint speaks. Not the look or the image but how the paint is acting. As such, a painting paints itself. I’m never sure what is going to happen next, but the painting knows. If I knew then the painting could not exist. (1)

Brennan touches here on a notable character of the contemporary works in all three exhibitions. The paintings and painted or ‘made-of-paint’ objects are generally not heroic, make no grand gestures, nor are they in any way part of an art world end game. Rather, there is in evidence an almost domestically iterative process of making, with lots of trial and error. There appears to be little pre-defined logic in many of the paintings observed, but rather an emergence of structure in the making. This emergent form is particularly evident in Brennan’s Trees, bodies, sky and water (2016) and Irene Hanenbergh’s small yet dramatic self-described ‘portal’, Hank (2014) shown in Painting. More Painting and in Julia Gorman’s Warm you up (2015) at GCAP 2016. This is not to deny the rigorous series of choices which also give Brennan, Hanenbergh and Gorman’s highly diverse paintings visual complexity, which rewards what the Filipino painter Manuel Ocampo has called ‘a slow read’.

Time-based art forms are the dominant cultural product of the moment. Interestingly, painting is not temporally ‘framed in the key of crisis’ like ‘everything else’ now as Jan Verwoert asserts, but instead, finds its own rhythm.(2) We are more aware of latency in recent painting. The realisation of an artistic idea is not the main game; there is a re-understanding of the temporality of the act of painting.

The canvas, in some artists’ work now, can be the residue of more performative practice, not in the deterministic way of the action painting of the abstract expressionists but as evidence or documentation of what happens elsewhere. Huseyin Sami’s experimental practise using thickly draped and adhered sheets of paint in his Untitled (PWGB) (2016) shown at GCAP 2016, and two ‘paintings’ in Shut up and paint capture the time, action and process of their making. The hybrid painting/sculpture Petal #1 (2015) which consists of pastel pink, blue and green paint sheets stretched over simplified flower wire forms, seen in Shut Up and Paint, emphasises the current blurring of boundaries between disciplines. Robert Andrew’s Family landscape #8 (2015), shown at GCAP is a trace of the artist’s process which combines the traditional media of his indigenous ancestry and contemporary robotic spray painting technology.

Victoria Lynn, a judge for the GCAP 2016, said in a recent interview that ‘painting can no longer be considered a single category, as there are so many different ways in which painting can be understood… post-conceptual… part of an installation… even sculptural’.(3) In that context painting is, in Braco Dimitrijevic’s words ‘no longer a sacred object, an icon that cannot be touched – it is easier to penetrate all layers of meaning of a painting in [an installation] than to recognize the values of the same work when it is simply hanging on the wall’.(4)

In this post-disciplinary world, you also need a set of reasons to curate paintings in a disciplinary-specific way. A well-known painting prize like the GCAP for example needs to ‘compare apples with apples’ to come up with a set of judgement criteria and award the $30,000 prize. Adjacency to the concurrent David Hockney exhibition is the ‘reason’ for Shut up and paint – and to bring an expanded notion of painting found in the NGV collections from the second half of the 20th Century into dialogue with those from the last 15 years, by Australian and international artists. Painting. More Painting seemed to have a curatorial point to make, but perhaps didn’t quite make it. The three curators were very much ‘present’ in the space over the two iterations of the exhibition, especially in the commissioning of a wall mural which made the paintings and audiences ‘work harder’, but seemed somehow in denial about their mediating role in selecting their alphabetical list of artists, and the chosen few who were allowed more than one work in the exhibition series.

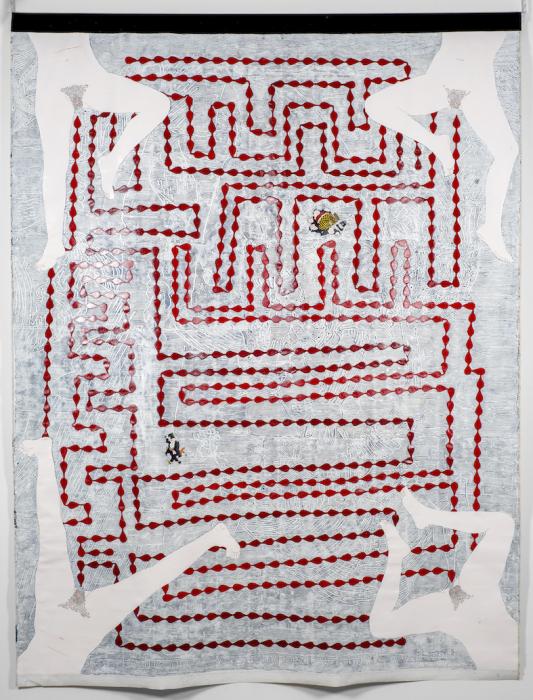

‘Painting’ says Jan Bryant, is interconnected with ‘other processes and histories’.(5) Brisbane-based artist Karen Black’s trajectory exemplifies this idea. Since she shifted into the visual arts from a successful career as a costume designer, her work has included oil paintings on wood which she, in her own words sets up ‘as if they were stage plays… I pit characters against each other’. Guard the opening gate (2013) in Painting. More Painting, for example references the sinking of the boat known as SIEV 221, which resulted in the death of 50 Iraqui and Irani asylum seekers, off the Australian territory of Christmas Island in December 2010. In another material choice, Black has been making painted ceramic works like Crown leg arm and Rooftop at night (both 2016), shown in Shut up and paint.

In artist and writer Helen Johnson’s words, there is something productive in painting’s ‘status as an emblem of bourgeois cultural production, the idea of it as anachronistic, its readiness for commodity status’. She thinks these things are ‘residual in the medium itself and can be used to make meaning’. Painting, she says can ‘offer distance from the established narrative, can change our sense of ourselves in the world’.(6) Johnson’s recent political banner-like works which include History painting (2016) and My word (2016) shown in Painting. More Painting after being exhibited at the Glasgow International earlier in the year, are enriched by their encoded status as objects, and graphically illuminate the historical stories we Australians tell about ourselves.

A reworking of modernism is evident in all three exhibitions, interconnected with the recent ubiquitous re-enactment of 1960s and 70s performance art and restaging of exhibitions, to be seen on a large scale in Melbourne soon with the NGV’s upcoming version of their 1968 exhibition The Field.

Mitch Cairns’ Geranium pots seen in Painting. More Painting is a series of vignettes taken from advertising and everyday life, with an early modern graphic quality, unified by a painted brick wall border. Two younger Melbourne-based artists in the same exhibition, Kirsty Budge in her work Always late to the party (2016) and Josey Kidd-Crowe in Goog boy (2015), reference late modernist works in palettes and motifs. It is an appropriation with a light touch, which seems to be more about acknowledging and referencing historical precedents than post-modern critical questioning of the canon. Styles and ideas from an historical context are made current.

Perhaps this recurring return to modernism is a pushback against the conceptualists’ emphasis on language, and its crucial role in visual experience and understanding, in a Web-based era where the visual dominates. The single picture in a frame calls attention to the multitude of images we view each hour in our smart phone frame. The difference is, however, that painted images have currency and value, as the deluge of digital images does not seem to do. As Boris Groys has noted ‘in reality, the diversity of images circulating in the mass media is highly limited… much more limited than the range of images preserved, for example, in museums or produced by contemporary art’.(7)

The work of some of the younger artists seen in the three exhibitions, most notably Ry David Bradley’s, has been characterised by commentators as ‘post-internet’, a term coined by Los Angeles artist Marisa Olson in 2008 and said by her to be less art on the internet than art after the internet ‘the yield of my own compulsive surfing and downloading’.(8) It has been making its way offline and onto gallery walls. It is work that speaks specifically to our time, to how we perceive depth and dimensions, because of our immersion in the digital and Web 2.0 Graphical User Interfaces.

Kate Tucker, in her Make space (2015) at GCAP 2016 has covered a wooden board with digitally printed cloth, onto which she has built up layers of acrylic emulsion, linen, vinyl paint, acrylic and oil before applying a topcoat of wax varnish.(9) The multiple layers only partially conceal each other, exposing the process of making. Viv Miller’s Enter (2015), also shown at Geelong, is a paradoxical work that uses multiple digitally sourced motifs and grid structures which appears both flattened and overlaid, in a simultaneously compartmentalised and all-over design.

Diena Georgetti’s Armour, History and Raider, all from 2016, seen at ACCA, use unrecognisable fragments of images of artworks sourced online, from diverse genres including 1950s abstraction and Op Art, in assembling her collage-like acrylic marks on canvas. The artist sees her paintings as a performance of the identities of the artists who came before her.

David Jolly emulates the materiality of the screen by painting photo-like images which he sources from photos taken in his own life on the reverse of glass, in a nod to our primary image-viewing mode and as a way of re-enacting his everyday experiences.

Even Juan Davila, formerly a painter of the grotesque, ‘wanting to push the medium of painting towards the ridiculous, to use impropriety and wrongness to open cracks in the ideological system of painting’, in the words of Manuel Ocampo, invokes the digital mediation of our world of the ironically titled abstract painting Being-in-the-world (2015) shown in Painting. More Painting.(10) He does this by placing motifs of a video ‘play’ symbol at the centre and a selfie-stick to one side of the abstract composition. His recent interest in the intersection of landscape and culture is seen in the inclusion of Woman by the river Yarra (2008) in Shut up and paint, a poetic and uncharacteristically harmonious work.

A surprising interest in the surface remains important for many contemporary painters. Some eschew the brush stroke just like American artist Helen Frankenthaler and others of her generation shown alongside the contemporary Australian work in Shut up and paint did. Ry David Bradley, for example, finds other ways to make surfaces look like paintings in the series of double-sided two-panel works NTBD (2015). In these works and in Border Protection 6 & 7 (2015), Bradley openly builds on Sigmar Polke’s technique of ‘machine painting’, in which the German artist tinted and altered images on a computer, then photographically transferred them onto large pieces of fabric.(11)

It is becoming clear that disciplinary categories long used for demarcating art school departments and contemporary museum collection areas and exhibitions are becoming redundant. As Melissa Chiu said at the keynote address of the 2016 AAANZ Conference in Canberra, the artist’s ‘intent’ makes far more sense than discipline, as an organizing principle for contemporary art.

- Jan Bryant, Painting. More Painting, ACCA, Melbourne, 2016, 27.

- Jan Verwoert, ‘Why are Conceptual artists painting again? Because they think “it’s a good idea”’. Keynote speech for the 36th Association of Art Historians Society Conference at the Glasgow School of Art.

- Personal communication with the author.

- Artist’s website, www.bracodimitrijevic.com.

- Bryant, Painting. More Painting, 25.

- Jennifer Higgie, 8 Painters on Painting, Frieze.com feature, 11 January 2013.

- Boris Groys, Art Power, MIT Press, Cambridge Mass., 2013, 18.

- Regine Debatty, “Interview with Marisa Olson” (2008), We Make Money Not Art, http://www.we-make-money-not-art.com/archives/2008/03/how-does-one-become-marisa.php

- Amelia Winata, “Kate Tucker: Tablets”, Daine Singer Gallery, http://www.dainesinger.com/amelia-winata-kate-tucker

- Gina Fairley, “A PIZZA DELIVERY (2011). A Conversation with Manuel Ocampo”. http://plantingrice.com/

- Ry David Bradley, “Novelty and Whatever Comes Next After Contemporary Art”, Pool, http//pool.info, 7 November 2011.