Red Pill and the Success of anti-post-internet art

In Matthew Greaves’s Untitled (Secrets of the Female Mind) (2013) a male artist makes a work about a woman talking about how stupid women are. The video was part of Red Pill, the second exhibition at Perth’s Success gallery in early 2016.(1) Red Pill was ostensibly about radical masculinities, a freak show of secret guy stuff. There was a glowing bar fridge full of monster energy drinks and a cherub pissing into a pool that stank of male deodorant. The conceptual core of the show lay in a side-gallery where the pseudonymous Alan Smithee set up a series of televisions installed into changing cubicles. Playing on them were youtube videos of people in gimp suits, urinals and baggy pants. Typical of the video performers was wetsoldier, a dentist from North America who wears outdoor clothes in baths and pools, sensually rubbing himself in his heavy gear.

The main gallery featured a video art take on this kind of online perversion. Jon Rafman’s Still Life (Betamale) (2013) remixes this kind of material into a screen within a screen.(2) But it is the intimacy of the changing cubicles that best simulates the way the internet remakes the distinction between public and private, as one man’s perversion meets the voyeurism of a micro-community of subscribers. In a final cubicle Smithee broke through the back wall to install a white, highly chlorinated pool floating a series of hypercoloured, folded islands, with Google’s Siri reading text from a reddit group about men’s rights overhead. It is as if we have reached Red Pill’s reptilian brain, a psychic picture of the minds of those who both hide behind and expose themselves on the internet.

In many ways, Red Pill’s corridor of perversion distils something of the whole Success phenomena. Its booths were in fact changing rooms left over from the old menswear section of the old Fremantle Myer building where Success, run by a collective of artists and volunteers, installed itself for a year. The booths stood in claustrophobic contrast to the expanse of floorspace that makes up the main gallery, a space that the curators left mostly pitch black. As reviewer Anna Dunhill writes, ‘Spot-lit islands glimmer off the pillars that stretch into the distance… It’s fifty metres of darkness in every direction. SUCCESS is not like any other place I’ve seen.’(3)

The curators built and unbuilt galleries within the space as the year progressed, so that every new instalment of exhibitions needed to be navigated carefully lest one miss a new doorway or a work hidden in the dimness. Just as the eerie space contrasted with the classically bright spaces of a conventional art gallery, the name Success enacted a short-circuit between the relation of established and emerging artists, hopes and dreams. For the gallery installed international artists beside locals and youtubers, as if indifferent to the origins of its own art supply.

To track the precise logic of Success, its parallax of youtube videos and the institutional artworld, it is worth delving into the history of the Red Pill exhibition, an online history of contretemps between Facebook moderators. Smithee drew these weirdly perverse, self-depreciating videos from a Facebook group that he moderated called the BOB DYLAN GLORY HOLE. Yet he would bring about a rupture in the group when he exhibited a selection of them in the Peek-a-Boo Gallery, a single street level window in Northbridge, Perth in 2014.(4) This crossing from a member only Facebook forum into the public sphere, and Smithee from member to moderator to curator, offended Matthew J. Mason enough that he created his own breakaway group, the WOODY GUTHRIE RUB ’N’ TUG.

Mason was already co-moderating one of the most successful Facebook groups in Perth, PL8SPOTTING, that had thousands of members uploading pictures of personalised number plates. This group was something of a Perth in-joke, as personalised plates like PERTHLING and SIC EMO are popular on the streets of the city. But Mason also came to sabotage PL8SPOTTING after people began taking selfies in front of their own personalised plates (like B1G NUT5 in front of her new ute). The in-joke had turned back upon its creator, and become a forum for the kind of self-affirmation that the group had been set up to parody. Mason wanted to maintain a distinction between a micro-community of self-selected ironists and the community at large.

Yet Mason too would succumb to the curatorial temptation, putting on the True and Utter Luxury exhibition at the HQ Gallery later in 2015.(5) This drew inspiration from the youtube star Archie Luxury, installing a shrine to his channel and a series of simulated channel artefacts. Here Mason shifts from one micro-community to another, from a self-selected online crowd to a self-selected artworld, each mimicking each other to create knowing audiences that wink at each other’s knowingness. Such contexts set up a game of sincerity, as nobody knows who is taking the piss out of whom, or whether curators, online stars and audiences are being ironic or not. Perhaps it is more the case that online perverts, internet stars and curators have no more idea of what they are doing than their audiences do. Youtube channels and exhibitions stage an irreconcilable relation to oneself, a theatre within which artists and youtube stars play themselves.

It is tempting to use the term ‘post-internet art’ to describe Red Pill’s mediation of the internet in the gallery.(6) Post-internet art is often used in the pejorative, to describe the way that the installation shot has come to stand for artwork itself, and to condemn the commercialism of the gallery system. Brian Droitcour describes the problem as ‘Walking around the flimsy plinths, which were arranged in rows to suggest a sense of depth that each lacked alone, I felt like I was an intruder on a stage set that would be photographed and rephotographed as soon as I got out of the way.’(7) Instead of Smithson’s distinction between site and non-site, post-internet art makes a distinction between the non-site of the internet and the non-site of the gallery. Instead of Walter Benjamin’s theory of original and copy, we have a theory of copy and copy, work that is designed as a copy that is then copied into the gallery. This is the dissatisfaction of post-internet art: it is made as if it was somewhere else, yet here it is in the gallery.

For Success, however, the internet is more of a tactical necessity than a career strategy. It answers the problems of running a space that cannot afford to ship international art but can download it. In the changing rooms of Red Pill this strategy became duplicitous, in a post-internet cynicism that put work into the gallery that could already be seen online. This duplicity is not quite post-internet, but instead returns to the internet as a kind of bottomless bucket, from which Success mines and dematerialises its artworks.

It is possible to map Success against other Australian galleries that work to navigate the contradiction of a post-internet world, in running a physical space while depending on the online universe to profile artists and exhibitions. Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery is paradigmatic in this sense. Situated in an obscure valley in the expensive suburbs of Sydney, Oxley is difficult to find, but there is also no point in an actual visit, since the gallery’s excellent online site and installation shots bring the exhibition into the browser. Yet in remaining tied to exhibitions and objects, Oxley also illuminates an anti-internet artworld, that does what it must online but also relies on actual artists and objects to promote and sell.

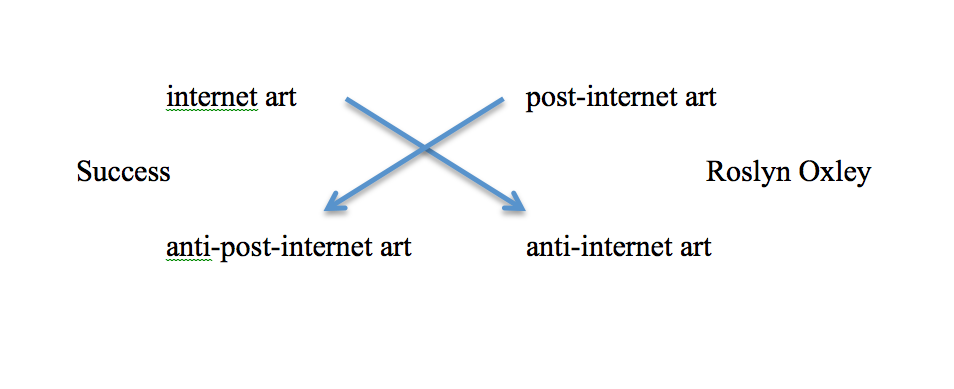

To map the contrary and contradictory responses of Success and Oxley to the post-internet era, it is possible to turn to a semiotic device known as the Greimascian Square. While the horizontal first line of internet and post-internet present unresolvable contraries, these logically generate a second line of contradictions (see images below).

While Oxley represents the tensions of both needing the internet (hence post-internet) and material artworks (hence anti-internet), Success needs the internet (literally internet art) but does not need artworks (in the sense that it does not differentiate between artworks and non-artworks, the object and non-object of an internet video).

The contradiction of being anti-post-internet lies in having a gallery in the first place, as the material labour of installing and running one is unnecessary to art that is already online (internet art). With the advent of the internet, of video art and youtube, art no longer has the guise of labour, of the art as work. Yet this work is also necessary to art, a work necessary to turn wetsoldier’s secretive smile from one of pleasure into a smile at the labour of making art.

(1) Red Pill, Curated by Dale Buckley, Success, Perth, 30 April - 30 May, 2016

(2) See https://vimeo.com/75534042

(3) Anna Dunhill, ‘The number you have reached’, Un Magazine, 10:2, 2016, 120-123. Available from: http://www.unprojects.org.au/magazine/issues/issue-10-2/the-number-you-h...

(4) Lovers, Curated by Alan Smithee, Peek-a-Boo, Perth, 16 - 30 July, 2013

(5) True and utter luxury: A meditation on indulgence in the 21st Century, Curated by Lyndon Blue and Matthew J. Mason, HQ Gallery, Perth, 7 – 21 August, 2015

(6) Another way of thinking about Red Pill is in terms of the legacy of white male identity art that arose in Australian art of the 1990s, by such luminaries as Ricky Swallow and Shaun Gladwell. As Anthony Gardner has argued in his prescient essay, ‘Whither the Postcolonial’, their carvings and videos of baseball caps and skateboards took the strategies of identity art staged by Aboriginal and multicultural artists and applied them to subcultures rather than ethnic and indigenous cultures. There is, however, no street culture for the online exhibitionists of Red Pill to join, and instead their interests must remain cloistered online, sprinkled with abuse from passing trolls. See Anthony Gardner, “Whither the postcolonial”, in Global Studies: Mapping Contemporary Art and Culture, ed. Hans Belting, Jacob Birken, Andrea Buddensieg and Peter Weibel, Oxtfildern, Hatje Cantz, 2011, 142-157.

(7) Brian Droitcour, ‘The perils of post-internet Art’, Art in America, 102:10, November 2014, 110-119 at 118.