Alterations: the hybrid legacies of Gordon Matta-Clark

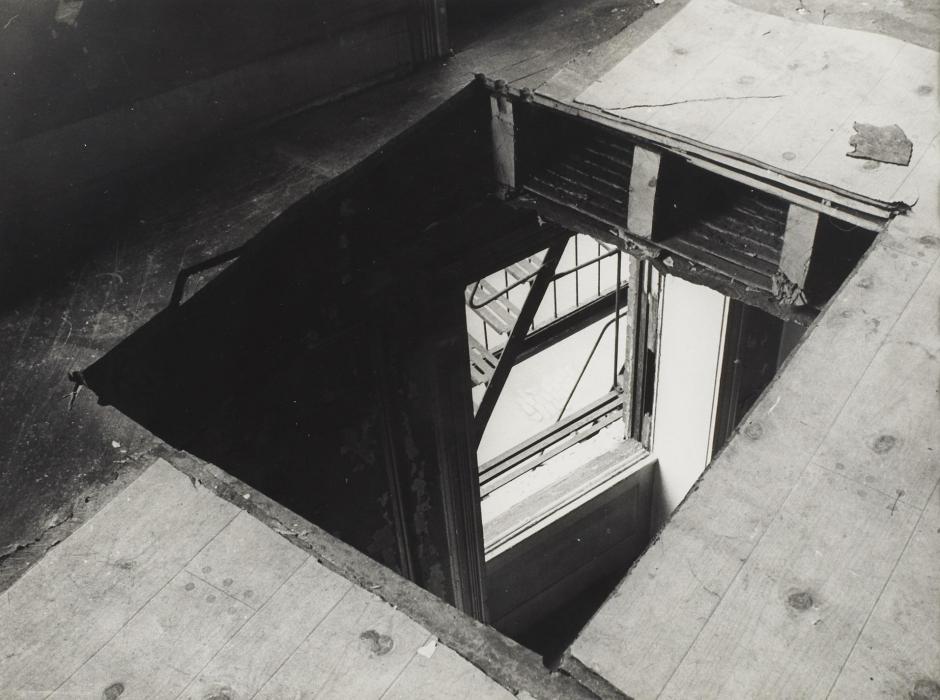

Sited atop a low-rise office block overlooking the bustling Flanders seaport of Antwerp, the American artist Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-78) and his assistants are industriously sawing a pair of circular holes from the building’s roof. To passers-by on the street below the men could pass for labourers. This inconspicuous appearance belies, however, the bold ambition of their project, now known as Office Baroque (1977), and documented in the film of the same name, which was to create what Matta-Clark describes in the film as ‘a layered drawing that the viewer participates in’—an intricate series of intersecting cuts and voids across multiple storeys today recognised as one of the artist’s most spatially complex building dissections.

Currently screening as part of Ecstasy: Baroque and Beyond, an exhibition at The University of Queensland Art Museum curated by UQ Renaissance scholar Andrea Bubenik, Office Baroque is presented among an eclectic display taking as its starting point the intensity of feeling embodied in Bernini’s iconic sculpture, The Ecstasy of St Teresa of Avila (1647-52). From the divine light of the Italian baroque dome ceilings photographed by David Stephenson to the sumptuous chiaroscuro interiors of Bill Henson’s triptych, Untitled (1983-84), the exhibition effectively sites Matta-Clark in a continuum of artists whose work exemplifies the passionate desire to surpass and overturn the limits of ordinary experience that defines the baroque sensibility.

Its inclusion also points to the expanded context in which Matta-Clark’s practice now circulates nearly four decades since the artist’s passing in 1978 from cancer at just 35 years of age. As the fortieth anniversary of his death approaches, it is pertinent to consider just what it is, precisely, about Matta-Clark’s deconstructed oeuvre that continues to hold the interest of subsequent generations. How is it that the very absence of a body of work that once troubled his earlier critics has given way to so much speculation, a site of reimagining that sees the artist continually remade in keeping with both historical and contemporary preoccupations?

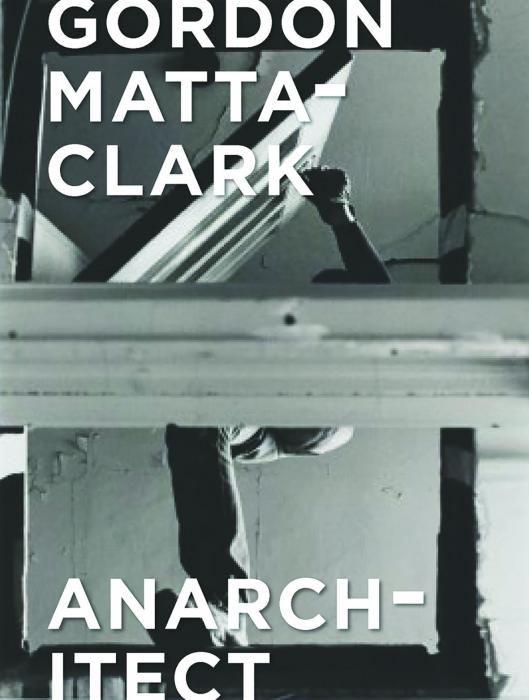

A new book published by Yale University Press to coincide with an exhibition of the same name at The Bronx Museum of the Arts in New York, titled Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect, typifies what is perhaps the key shift in the reception of his work in recent years. Where art history scholars were once principally concerned to redress the omission of Matta-Clark from the canon of 1970s minimalism, conceptual art and site-specific strategies (1), contemporary interest focuses on the artist’s inherently critical relationship to architecture and the ongoing relevance of his interventions to the urban politics of the present day. At the heart of this reappraisal is a significant détournement (turning around) in the understanding of the controversial role played by destruction in the artist’s work.

When Matta-Clark took a chainsaw to a two-storey home in suburban New Jersey, cleanly incising it down the middle for his first major building cut, Splitting (1974), the destructive methods of his practice were largely cast in negative terms. From accusations that his New Jersey cutting represented ‘out and out rape’ of a house (2) to the filing of charges against the artist for his unauthorised cuts into an abandoned Hudson pier warehouse for Day’s End (1975)—the building cuts were construed as an assault on architecture, and Matta-Clark cast as a fugitive producer of a distinctly anti-modernist and violent form of anti-architecture.

By contrast, Matta-Clark himself sought to emphasise the inherently transformative intent of the cuts, seeing them as ‘a special stage in perpetual metamorphosis,’ (3). The essays presented in Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect reflect the extent to which current responses are concerned to recoup the productive tensions of the cuts and, as such, offer more sympathetic readings of Matta-Clark’s relationship to destruction. At the forefront is a distinct emphasis on the socially conscious nature of his project and the backdrop of radical social upheaval against which it unfolded. In keeping with the affective turn in critical theory rooted in the rhizomatic thinking of Deleuze and Guattari, the building cuts are similarly recast as generative in so far as they sought to actively alter the visitor’s bodily relation and sensed perception of built space whilst setting in motion a critique of the processes of urban renewal. If it’s been noted with some ambivalence that Matta-Clark is frequently ‘made into the artist who satisfies the needs of the person who is writing the book,’ in the words of peer Richard Nonas (4), the diversity of responses presented in this volume point to the malleable and shape-shifting quality of Matta-Clark’s oeuvre that nonetheless warrants acknowledgement as one of its strengths.

Furthermore, the book’s focus on anarchitecture enables a valuable line-of-flight from well-rehearsed biographical details. The term ‘anarchitecture’ is an unstable and open-ended signifier, as readily implying an-architecture and anarchy-tecture as anti-architecture, and now readily adopted as a catch-all description for Matta-Clark’s practice. It is important to acknowledge, however, the term’s collective origins. Over the course of a year from 1974 to 1975, a dozen or so artists from the downtown scene met regularly to workshop anarchitectural ideas. Crafting proposals, manifestos and speculative-poetic texts that experimented with alternative approaches to the built environment, the rubric of anarchitecture became a way for the group to think about the city’s ‘metaphoric voids, gaps, left-over spaces, places that were not developed,’ Matta-Clark explained (5).

In Matta-Clark’s era, the South Bronx neighbourhood where he lived and worked was undergoing such severe urban blight that the artist’s pulling apart of abandoned or disused structures arose from an ethos of repurposing and recycling. Since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, there is renewed concern on the part of artists to work with architecture at the scale achieved by Matta-Clark as in the interventions of Australian artist Ian Strange, for instance, who has cut and overpainted foreclosed houses in the rust-belt of the USA. More broadly, the deterritorialising spirit of anarchitecture finds contemporary parallels in the proliferation of experimental design bureaus around the world. It can take the form of actions as in such projects as Letters to the Mayor (2014) and the reimagined building icons of Souvenirs (2017) presented by the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York. Closer to home, the bio-architectural practice of the Laboratory for Visionary Architecture (LAVA) and the porosity projects of Richard Goodwin, which break apart readymade ‘small architectures’ like tents, cars, pushbikes and rowing sculls to make porous the interface between private and public space, test new possibilities for urban metamorphosis.

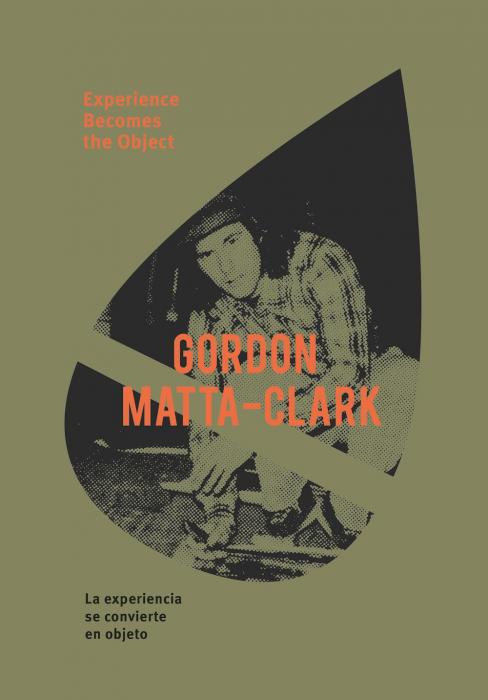

If Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect strives to bring new critical perspectives to bear on the artist’s practice, another recent monograph titled Gordon Matta-Clark: Experience Becomes the Object, presents a more personal point of view, drawing widely on the testimonies of friends, relatives, collaborators and peers with a view to documenting the inherently collegial nature of his work. Published in association with an exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Santiago, Chile, where Matta-Clark made a small-scale intervention into one of the building’s corners in 1971, the book is deliberately partisan in its approach. For as one contributor notes, ‘We cannot nor should not expect the objectivity of a scholar from those who were actually part of the action’ (6).

The transcript of a talk by the American artist Gerry Hovagimyan recounting his time assisting Matta-Clark on the major projects Day’s End (1975) and Conical Intersect (1975), is especially revealing of the extent to which the cuts relied on the contributions and good will of others. At the same time, Hovagimyan brings to life the remarkable physicality and technical improvisation of the cuttings. In Paris, where Matta-Clark was provided with a pair of soon to be demolished 17th Century townhouses to cut for the 1975 Biennale, the buildings were without electricity meaning the artists tunnelled the telescopic conical cut with hand tools and brute force. Typically, such anecdotal evidence sits uneasily with the rigour expected of conventional scholarship. In the case of Matta-Clark, however, the testimony of participants, collaborators and visitors provides an important counter-narrative to the myth of the heroic individual. It is also a means through which to resist the commodification of the traces and documents that have come to stand in for the bodily experience of modified space that constituted the work.

In reading the many words penned on Matta-Clark’s life and work, there is no doubt an aura of romanticism shrouding this fleeting period in history when it seemed possible to actualise the avant-garde imperative to overcome the distinctions between art and everyday life. Yet as the astute presentation of Office Baroque in Ecstasy: Baroque and Beyond demonstrates, the value in reconstituting Matta-Clark is not to reify a life and time already past. Rather its worth lies in the taking up of an unfinished project that still speaks to the concern of present generations to destroy the limits of building, not for destruction’s own sake, but to elevate architecture beyond the status of mere real estate, placing it at the service of altering and expanding the possibilities of the real itself.

Ecstasy: Baroque and Beyond, The University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, 16 September - 25 February 2018.

Antonio Sergio Bessa and Jessamyn Fiore (eds), Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect, New Haven: Yale University Press and The Bronx Museum of the Arts, 2017.

Pedro Donoso (ed), Gordon Matta-Clark: Experience Becomes the Object, Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafia, 2016.

Notes

(1) For the foundational work of art historical scholarship on Matta-Clark see Pamela M. Lee’s doctoral thesis turned full-length monograph, Object to be Destroyed: the work of Gordon Matta-Clark, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000.

(2) Artist interview transcribed in Gordon Matta-Clark exhibition catalogue from 1977. Quoted in Lee, Object to be Destroyed, p. 21.

(3) Gordon Matta-Clark typewritten statement (undated), reprinted in Gloria Moure (ed), Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings, Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa, 2006, p.132.

(4) Richard Nonas, ‘Gordon did a Dance with Life,’ in Pedro Donoso (ed), Gordon Matta-Clark: Experience Becomes the Object, Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafia, 2016, pp.166-67.

(5) Artist interview with Liza Béar first published in Avalanche, December 1974. Reprinted in Moure (ed), Works and Collected Writings, p.166.

(6) Gwendolyn Owens, ‘From Multiple Perspectives Comes Understanding: Gordon Matta-Clark, Circus, and the Truth,’ in Donoso (ed), Experience Becomes the Object, p.93.