Postcard from Newcastle

The railway line gets dug up & artist impressions

emulate dreams of Copenhagen.

It can’t be sanitary… [1].

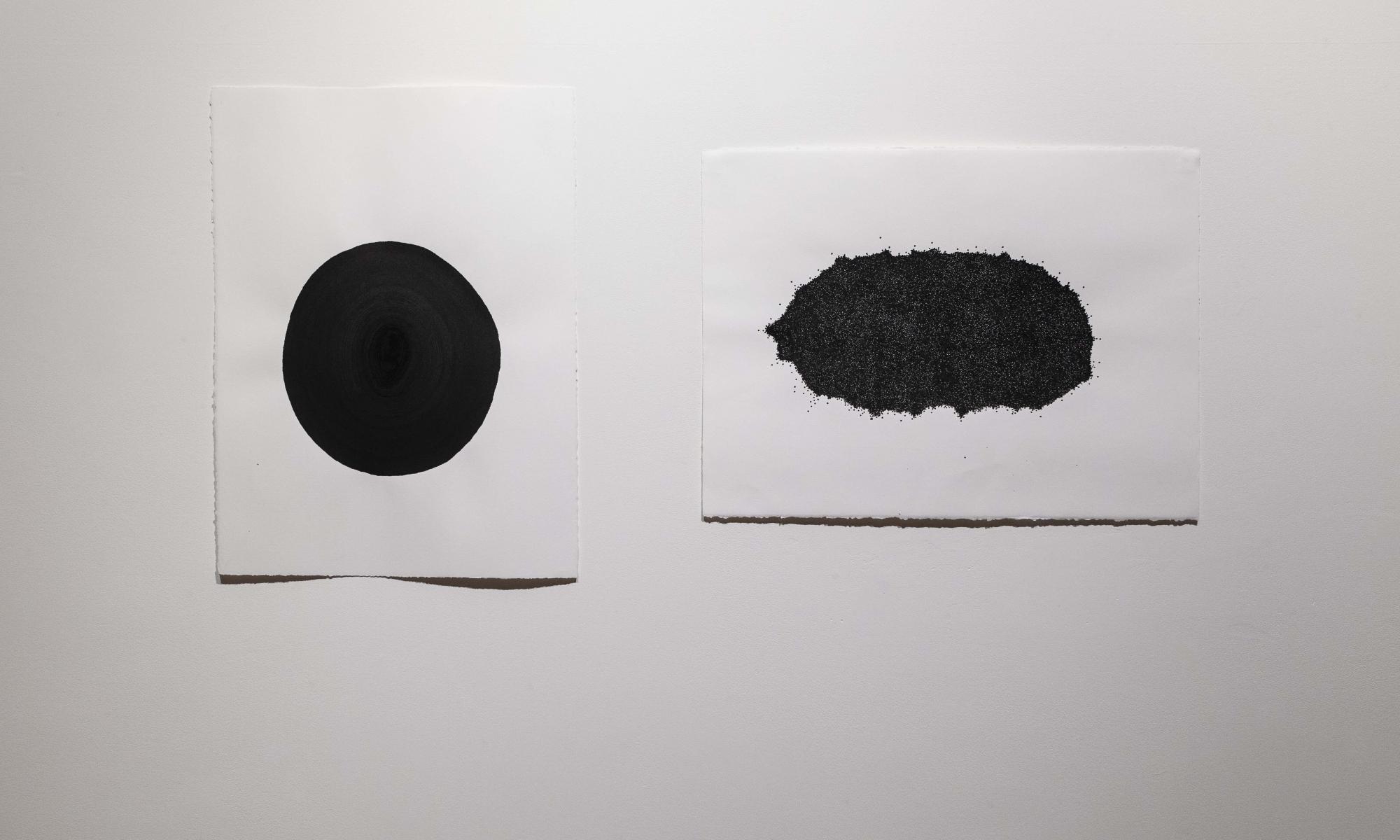

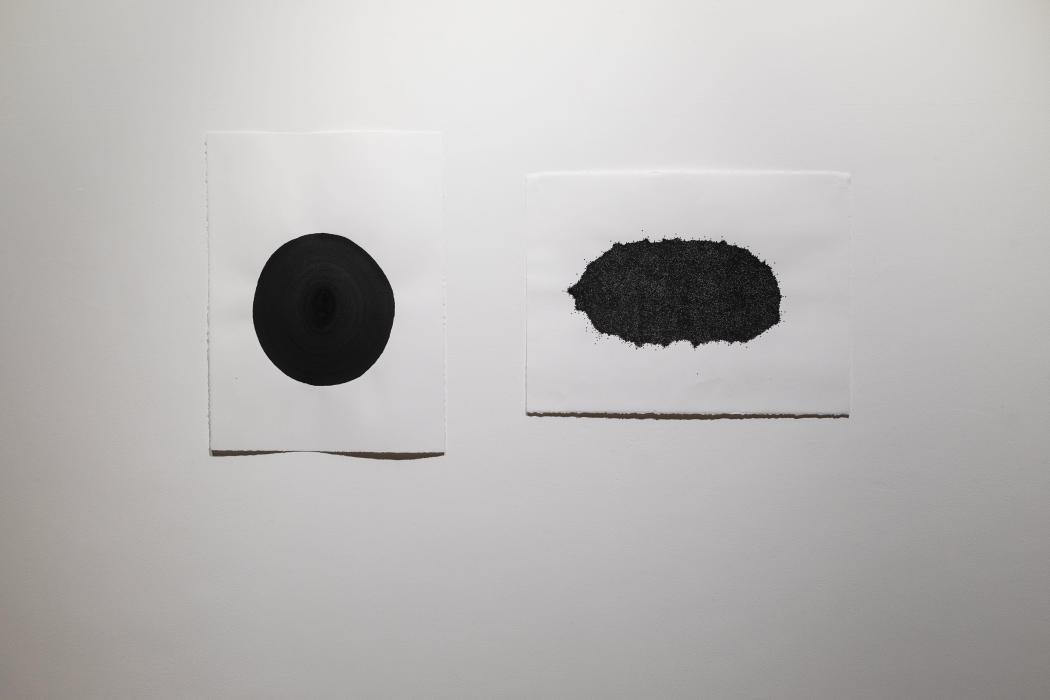

Gravity & Lightness (2018) is a diptych hung in the front room of Newcastle’s Lock-Up. In the left panel is a dense, dark circle that seems to radiate out from its own black centre, marked by ripples of congealed ink. To help you imagine what I mean: it looks like the cross-section of a tree trunk. In the right panel, smaller dots of that same black ink gather into constellation as they close in on the white space of the page. This panel doesn’t really look ‘like’ anything—at a stretch we might say it feels as if the dots have clustered around the centre of the frame like ants around some lump of sugar left on a benchtop. But that’s not really it. Here and elsewhere, perhaps, ‘likeness’ might not cut it as a mode of description.

I haven’t spent more than a Christmas holiday in Newcastle since I was a teenager. Returning as an adult to my smallish hometown, there are senses, simultaneously, of familiarity and alienation. There are senses also of both monumentality and smallness. My friends from Sydney ask me what it’s like, being back. Here, as well, it seems a disservice to say that it feels, or is, ‘like’ anything. Better perhaps to say what it is, what there is around.

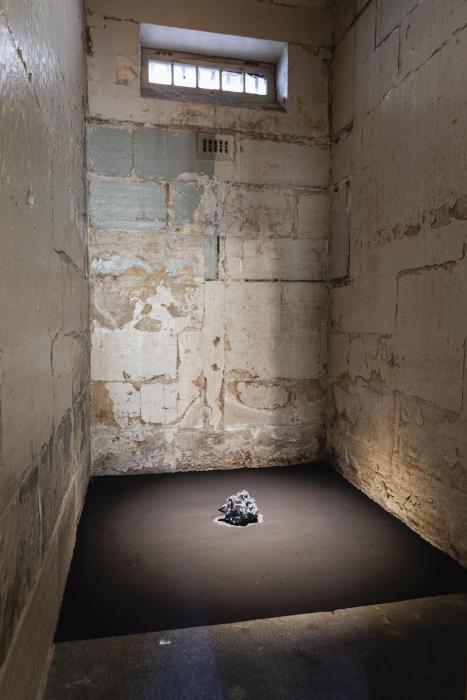

One of the things around in Newcastle is Emma Fielden’s show An Immeasurable Distance at The Lock-Up, in which Gravity & Lightness appears. Like many of the shows that the arts space hosts, Fielden’s work responds thematically and formally to the history of the site. That is, it thinks carefully about the socio-historical specificities it’s embedded in. A former police station and prison, with tags scratched into the walls, and cold, poorly-lit corridors, senses of physical and psychological entrapment still roll around the building. Fielden responds to this with a body of work exploring scientific and philosophical conceptions of the infinite. Delicately, she deals with the infinite as both a centripetal and centrifugal idea. The infinite might, here, refer to the vast reaches of space gestured towards in Distant Orbits (2016-2019), the installation of magnets, thread, and blue-light projection that occupies the main gallery space. It might no less refer to the impossibly minute; that which is ‘so small as not only to be invisible but capable, at a hypothetical level, of never-ending divisibility.’ [2]

I wonder if it’s the enormous or the minuscule sense of the infinite that Fielden posits as the distance between people who (attempt to) know each other more or less intimately in her video We are two molecules floating together in space and our distance is infinite…then the sound of birds (2018). This ambiguity is apposite. How much can we know the particularities of somebody or someplace else? If you ask Martha Nussbuam, whose work I’m reminded of when I see Fielden’s show, the answer is a limited amount. But this finitude makes it only more important, ethically, that we try to pay attention—which is to say, affection—to the stuff and people around us. In Love’s Knowledge, Nussbaum imagines that ‘responsible lucidity can be wrested from the darkness only by….the intense scrutiny of particulars’ (3). Newcastle-born poet Peter Minter, decades ago, wrote it a different way in Afternoon Swim, 22/11/91:

Enamoured by the swallows’ play

I float my face into the boiling sky,

try to show you singularity in difference [4]

The inconceivably big and the dazzlingly small — but also, the particular and the general, the evidence and the law—are treated even-handedly by Fielden. She looks at hypothetical systems through analogy in a way that never loses sight of the analogy itself. Her works are as conspicuously about ink and marble and iron as they are about scientific abstraction.

By comparison, walking around Newcastle again I am struck by the town’s nods to the global social and economic—even technological—system that it sits within. It’s hard to fight the temptation, that is, to not pitch this place as either a part of a larger whole, or as a likeness of something else. The ships on the horizon constantly gesture to distant nations buying and burning the coal that moves through the port. The town hall has been re-surfaced, rebranded, and renamed City Hall. Recently installed out the front of the Gym I go to is a billboard reading ‘London, Paris, Rome, Madrid, New York.’

Ideas of Newcastle as something broader and less specific than itself pop up again at the Newcastle Art Gallery. On the afternoon I go to see the finalists for the Kilgour Prize, I’m distracted by recognition of faces and artists from someplace else. Paul Ryan’s yeah the boyyyyzzz. eureka boys (2019), with its affectionate send-up of masculinity recalls the artist’s work from this year’s Archibald Prize. Tamara Dean, whose tender, contemplative photography I’ve long loved, has a painting here as well in a characteristic pink palette. There are the familiar faces of Jane Caro and Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran on the walls. I’m reminded that the subjects of portraits exist both within the work and somewhere else. They are both themselves and an analogy for themselves.

This doubling—this sense that what happens here isn’t only happening here—is itself doubled down on during a talk given at the Newcastle Art Gallery by Marion Buchloch-Kollerbohm, who directs the cultural mediation program at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo. Buchloch-Kollerbohm speaks about the history of her gallery’s site, emphasising that curators and artists are ‘inspired by the specificities of the architecture’ [5]. Detailing the gallery’s history as one of the earliest concrete buildings in France, originally intended as a gallery and then used as a warehouse for stolen goods in the occupation of WWII, Buchloch-Kollerbohm emphasises the affective duality of the site’s story: ‘it has a very exciting history in terms of history of exhibitions, but also a much darker one; if you go in the building you can feel both sides of the history’ [6]. Listen with faulty attentiveness—with what Nussbaum would call ‘obtuseness and refusal of vision’ [7]—and she could be talking about The Lock-Up. How far out this town’s concentric ripples reach.

During the first few weeks of my being home, Watt Space shows Objectify, this year’s iteration of the annual student art prize attached to Newcastle University. This year, students were tasked with responding to the object, and the idea, of the cocktail umbrella. The space is filled with Miami Vice-type bawdy colours, and uses of the umbrella figuratively, conceptually, materially. Some of the most striking work puns on the object inspiration. Annika Thurbon’s sad phallic sculpture Cock Tail (2019) slumps over the plinth it sits on. There’s both humour and vulnerability in its subject matter, but pushing against this is the athleticism, the ardour, of the sandstone stripes that run across its surface. There’s a productive and exciting tension between the representational and the material elements of the work. It is what it is, and what it is like. It asks us to be attuned—like Fielden’s work, like the Kilgour’s portraiture, and like walking around Newcastle all these years removed—to particulars, as well as potentials. It asks us to be attuned to what poet Keri Glastonbury registers as

the chicanery,

the chiaroscuro

of coal dust and sand (8)

[1] Keri Glastonbury, ‘The Production Hub,’ in Newcastle Sonnets (Sydney: Giramondo, 2018), 22.

[2] Julie Ewington, ‘Emma Fielden: The Whole and Parts of Infinity,’ catalogue essay for An Immeasurable Distance, The Lock-Up, September 2019.

[3] Martha Nussbaum, ‘Finely Aware and Richly Responsible: Literature and the Moral Imagination,’ in Love’s Knowledge: Essays on Philosophy and Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 151.

[4] Peter Minter, ‘Afternoon Swim, 22/11/91,’ in Rhythm in a Dorsal Fin (Parkville: Five Islands Press, 1995).

[5] Marion Buchloch-Kollerbohm, lecture given at the Newcastle Art Gallery, August 29, 2019.

[6] ibid.

[7] Nussbuam, ‘Finely Aware,’ 162.

[8] Keri Glastonbury, ‘Just Quietly Babe,’ in Newcastle Sonnets (Sydney: Giramondo, 2018), 29.