A Persian Letter

The poster is divided in half by a long blue Facebook ‘f’. On the right lower edge, the letter has been serrated, making it resemble a saw. The results of its actions can be seen in the house that has been cut in two, with husband and wife walking off in different directions.

This is a series of posters I found in the endless Mashhad bazaar, hanging over the shops selling turquoise and saffron, the staple of the region since the Silk Road. Other posters featured satellite dishes on top of tanks festooned with US and Israeli flags.

As a modern occidental, I'm inclined to read these symbols as propaganda imposed upon a hapless populace, itching to embrace the delights of Western freedoms. But my darker self finds some delight in them. I don't want the world to be one. Financial sanctions mean that international credit cards don't work in Iran. No Netflix, Amazon, Uber, Airbnb—the whole wave of placeless services has avoided this country. There's so much to enjoy in Iran that is but a distant memory in Melbourne.

There are flowers everywhere. The parks are full of families and friends. People look you in the eye, intently. And, especially, they believe in art, deeply, not just as a driver of an innovation economy.

Before making an important decision, it is custom to consult the Divan of Hafiz, the national poet. Opening the book at random, the poem reveals a way forward (naturally, there’s an app for that, now.)

I asked a weaver friend living in Tehran to do this for me, as a guide to putting together a special issue of Garland magazine about Iran. She came back with Ghazal #83. Hafiz is notoriously difficult to translate, but in its florid way it seemed to advise an acceptance of the past and a willingness to ‘move on’.

If your musk scented curls committed a sin—it’s gone;

and if your hindu mole has wrought havoc—it’s gone!

It turns out to be a serendipitous message for a country that is moving out of the shadow of the Axis of Evil, where both sides still have historical grievances, but recognise the potential for collaboration.

How might this unfold in art? I'm curious about the absence of modernism in Iranian culture. There seems little interest in stripping away the surface to reveal an immanent reality. While we seek to return nature to its pre-colonial truth, in native grasses and wetlands, Iranian gardens are all about visual splendour in intense colour.

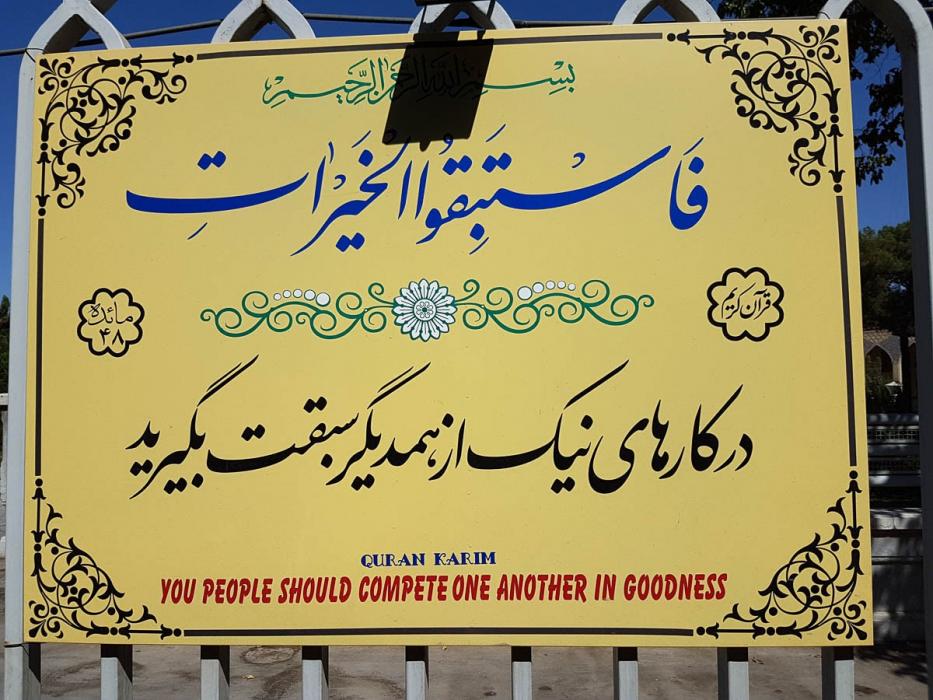

To think further about this, the theme for Garland's online exhibition is embellishment. One unifying element in Iranian art and craft is to adorn with intricate patterns. Sometimes it is the birds and flowers pattern (golvamor) from the Zandi period, other times it is the complex geometry of Islamic design. There seems no truth to materials here.

A thought may be developing in your mind as you read this. What about the repression of human rights? Am I just a gullible antipodean charmed by this faux aristocratic culture? Thanks to stories of refugees, we are familiar with terrible consequences of those who do not fit into the system in Iran. But in solidarity with their suffering, we are perhaps unwittingly complicit in a Western stereotype of Iran as an oriental backwater. Nothing is quite as it seems.

In Mashhad I visited the studio of an artist couple specialising in miniatures. Much of it was interlocking calligraphy, transforming meaning into pattern. As often happens, they insisted on my taking one of their works as a gift. I asked its meaning. Of course, it was Hafiz again. And the meaning? The husband with the curled moustache smiled, ‘The material world is nothing.’

Strange that a culture that does not believe in this world, invests so much in making it beautiful. Like.