An Island

Terror

What is yet to come was revealed in a terror of images to John, the Revelator. I could repeat to you some of those images, but you can read the revelation, for yourself.[1] It was written to be read. Some of the things that John imagines are impossible to visualise. Other visions are deeply inscribed, like the things with wings, popping with uncountable eyes that (John doesn’t say but I believe) can’t blink and which must slip and slide over themselves, chastening each other, when the wings fold against the body.

The revelation was given to John in a cave on Patmos where he was exiled by an emperor who feared what the Christians would do. I take a ferry to Patmos, which is dry and rocky and covered in eucalyptus and pine. I go to the cave. A priest sits to the left of the entrance, his black gown draped between his knees and his head resting on his hand, monitoring the impious and imperfectly pious. There are few of us. I don’t know the Greek Orthodox form of the religion, so I look.

Adoration

Everywhere there are surfaces for kissing. I know this from watching the other visitors who walk down the carpet, cross themselves and kiss the icons. They kiss in a way I have never seen before. Their faces come close, and lie oblique, mouth and ear and eye all equal to the icon, and for a moment they look like they are waiting for something, and then quick kisses, more than one. Then they withdraw and move sidelong, to the next.

They are not desiring kisses. And I cannot see how you could approach a person like that. It’s more like a mouth—the opening which everything necessary for life goes in and out of—is brought closer to another opening. Perhaps the mouth is not quite sure where that opening is, except that it is somewhere on this surface. It seems to me that the icon waits for those kisses. It waits for adoration.

Which I am not able to give. Whatever these visitors come face to face with in the cave of terrors, it does not appear to me just because I am here in front of the painting. And I don’t appear to it—we are blind to each other. I don’t see God and God does not see me.

Denial

I see these painted surfaces as opaque because I was taught to believe that it should be transparent, a window, a one-way window. The gaze passes straight through it to what is real. The real doesn’t look back.

Instead, a picture is like the snake in the original garden, who made false representations, and brought about our alienation from God, so that all contact in the future, until the end of time, had to be mediated. The icon was one solution to that. The other is denial: a picture might redeem itself, but only by being invisible, its surface denied.

Perhaps because there can be no window on God, the image makers and seekers turned to Nature, becoming empiricists.

Empiricism. The basic idea is that a person, a seeing subject, sees the world for herself, with her own eyes, and knows the truth, which is projected on to the surfaces of her mind, or her brain. It is the perfect image. And an impossible one.

Formation

We still talk about science as being empirical, but it is not. Scientists deal with information and probabilities and categories. They don’t create knowledge, they create discourse, which others then interpret.

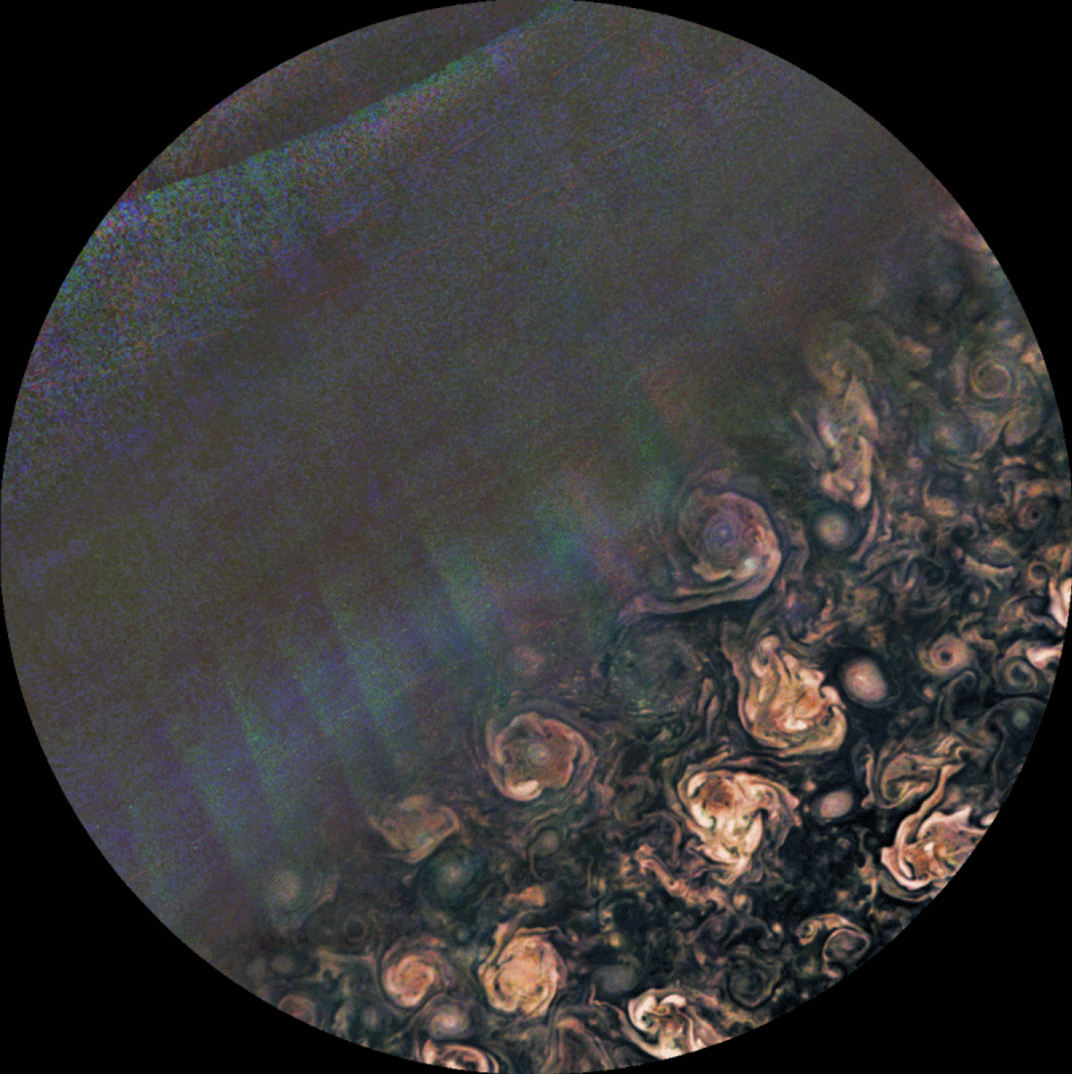

Here is a picture created by Gerald Eichstädt using data from NASA’s spacecraft Juno.[2]

The pixels in this picture have a precise relation to data, a quantification of types of information, which has been gathered with an instrument, a camera. So, now, we look at a form of information.

We use these formations to make claims about the existence of things, and about things to come. The visual form that formation takes is determined by our purposes (a very pure pragmatism).

This is a very different type of image from all the ones before. I think there is no surface anymore between two worlds. Instead, it looks like a phase change, a physical change from one state to another.

In the infinite darkness, Juno turns her eye to Jupiter. A data set is produced. Eichstädt used this data to make a movie. 41 frames. They are subtle images. I don’t know how to interpret them. I can only look. What I see is something coiling, something like many mouths, or something like the uncountable eyes. I see a wing lifting and folding, over and over again.

The island of the dead

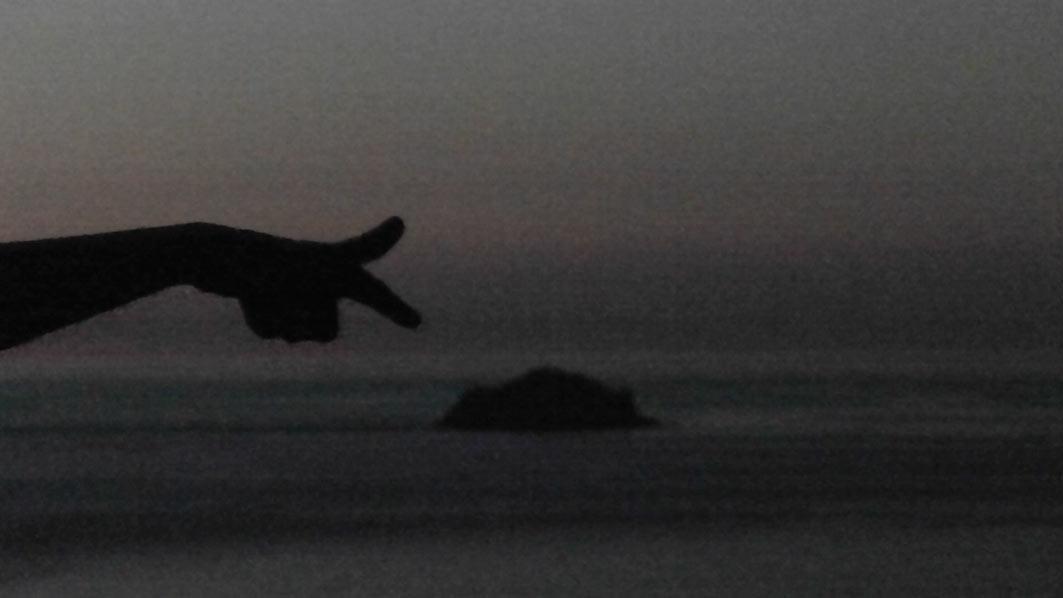

In The Island of the Dead (2014) Beth Collar appears to point, urgently and persistently, again and again.[3] She points, so there must be something there because that is what pointing is: it is the sign that tells you that something is there.

It is an island.[4]

It pulses as the auto-focus hunts for the edge. She appears in the frame and asks me (directs me, because she plays with the ambiguity of the grammar, but she also calls for my attention through pitch and intonation) to ‘Look at that rock over there’, then she leaves. She gets out of the way so that I can see.

Perhaps she is on an island, near an island, but I get the strong sense that I am looking at an image of an image, rather than a picture of a rock in the round. The picture is flat and coarse. Her finger hunts, like the camera, for its target. She is imagining herself as an image. She stands between that image and the island. She is pointing.

But not at the island. That hand is pointing. But not at the island.

So, this sign—which seems the most transparent and so basic that you don’t even have to learn it—is, after all, not a reliable sign of the existence of something.

I will never see where she is pointing, for myself, with my own eyes, because I can never see it—and we can devise no images to compensate for that. There is no terror, adoration, or denial of the image in The Island of the Dead, no surface and no separation into worlds. There is also no act of formation.

In the end, she tells me ‘when I die, I’m going to that rock, that rock in the sea. That’s where all the dead people go.’

Surfaces, a universe, islands

Terror, adoration and denial are attitudes to the unseen—and yet to be seen. They hold in them the belief that everything can be seen, and that we can make do with the surface until we can experience true reality, directly, on the other side.

But if the image is a formation then there is no other side. We are in a universe. We can get at what it is—if that is what we want—with images, which are ways of imagining, but this shouldn’t be confused with seeing what exists. The universe is not seeable. Its images are.

So, instead of two worlds separated by a surface, we have one world, in constant (trans)formation, some of it intentional, some of it not.

In The Island of the Dead the artist points at something that is not just unseen, it is unseeable, but not for the same reasons as the stuff of the universe is unseeable. No matter how much we need or want, we will not be able to devise an image or a way of making images, that shows us everything that is so that we can know it. It is a blind spot. If we try to fill it, it just wanders off to another sea or nestles under another wing.

[1] One translation of the Book of Revelation can be found at https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Revelation+1&version=NIV

[2] ‘Amateur’ processing of JunoCam’s image data are published at junocam.pictures. This link will take you to the video of 41 frames, referred to in the text http://junocam.pictures/gerald/uploads/20170424/anim/jnc_pj05_N_089_to_105_blend4_enh.html

[3] Beth Collar’s Island of the Dead is published on her vimeo page at https://vimeo.com/98592174

[4] The island of the Dead was part of an exhibition, Secret Surface, curated by Ellen Blumenstein, for KW Institute in Berlin in 2016. Terror, adoration and denial hummed constantly in the background or blared like the telephone in Hollis Frampton’s Surface Tension. In Trisha Baga’s work, I saw a leaky interface between one world and another. Auto Italia showed me how my skin is at war with a world of data (both inside and out). Art, conventionalised to some degree, chaotic in other ways, might secrete other possibilities of the image in its surfaces.