The tough guy of pop: An interview with Peter Phillips

Reclusiveness has always played a part in Peter Phillips' life and work.

A pop artist with a cool detachment from the social trappings of that particular scene in London and New York in the 1960s; a Brit who left the country in his twenties to live in America, Spain, Switzerland, Costa Rica and now subtropical Australia and who has always held artistic 'centres' at a deliberate arm's length; a creative practitioner who, despite the pop art label and critical alignment with artists ranging from Duchamp to Rauschenberg and Johns, has always held an immediately recognisable and highly original visual style, reflecting a mind that delights in the peripheries; Phillips has managed the singular trick of being seminal, without being all that social.

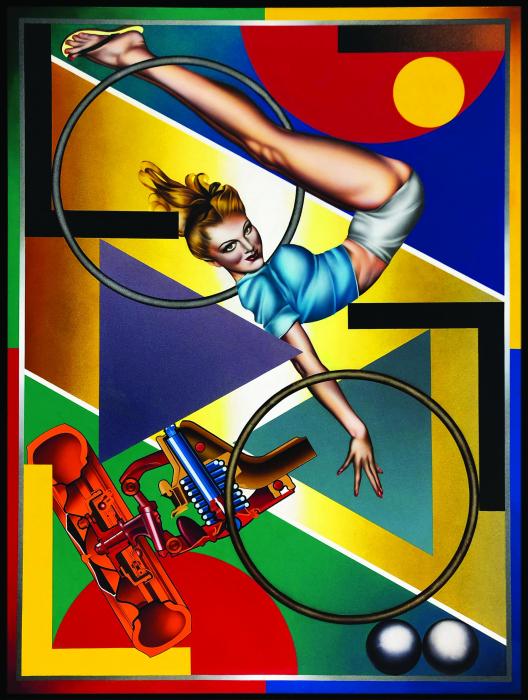

Not that his current home in Tinbeerwah, Queensland is particularly remote: Noosa is only a 15-minute drive away and Brisbane less than two hours. Phillips, just turned 80, lives here with his daughter, Zoe Phillips-Price, her husband Read Price, and their three-year-old daughter. Living in Australia as a result of a Distinguished Talent visa, Phillips works out of a home studio that houses many of his most famous pieces—including Art-O-Matic Riding High (1973-4) and the Star Card Table works (1962/2015), as well as paintings of the 1980s and 90s, such as Blue Study (1989), which beg obvious comparison with Joan Miro's collagism.

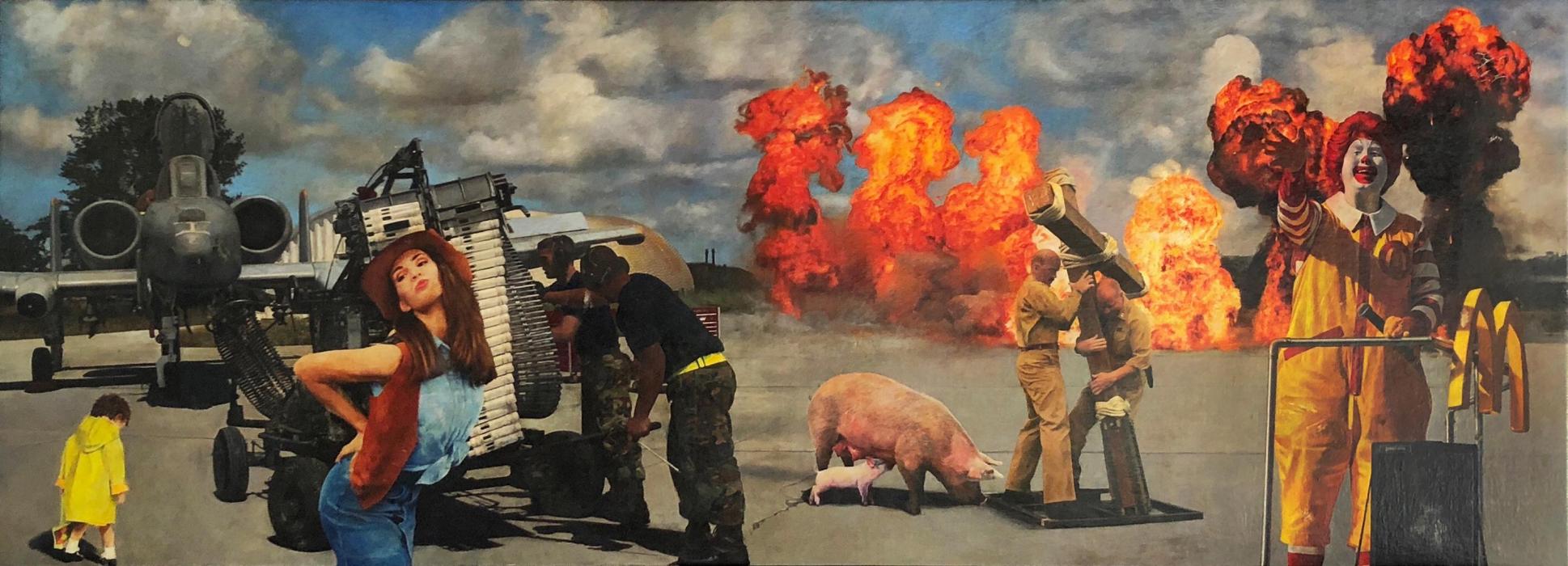

Other pieces include Feeding (2007-12), with its undertones of social comment and condemnation of American foreign policy, and the coruscating Rape of Australia (2012-14). Phillips has, however, long insisted that his work makes no political statement and should not be interpreted as such. One might, however, interpret as a political gesture his appropriation of commercial and 'everyday' imagery for his signature 1960s paintings, in keeping with the well-documented view that pop art utilised the optical language of marketing, movies and pop culture to make a statement of dissent. It's hard to argue this was ever Phillips's intention: as he tells me, his use of commercial imagery came about simply because it was at hand, and it stood out visually and colourfully. It is, after all, the intention of advertisers to catch the eye; they certainly caught Phillips', and his manipulation of adverts found in magazines and newspapers is neither a celebration nor denouncement of them. If anything, he is bringing an accessibility and sense of play to art—a counter to the dour traditionalism that Phillips and his contemporaries (such as Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and David Hockney) were force-fed at the Royal College of Art in London.

Marcel Duchamp once said, ‘I was interested in ideas—not merely in visual products.’ The exact opposite of that might apply to Phillips.

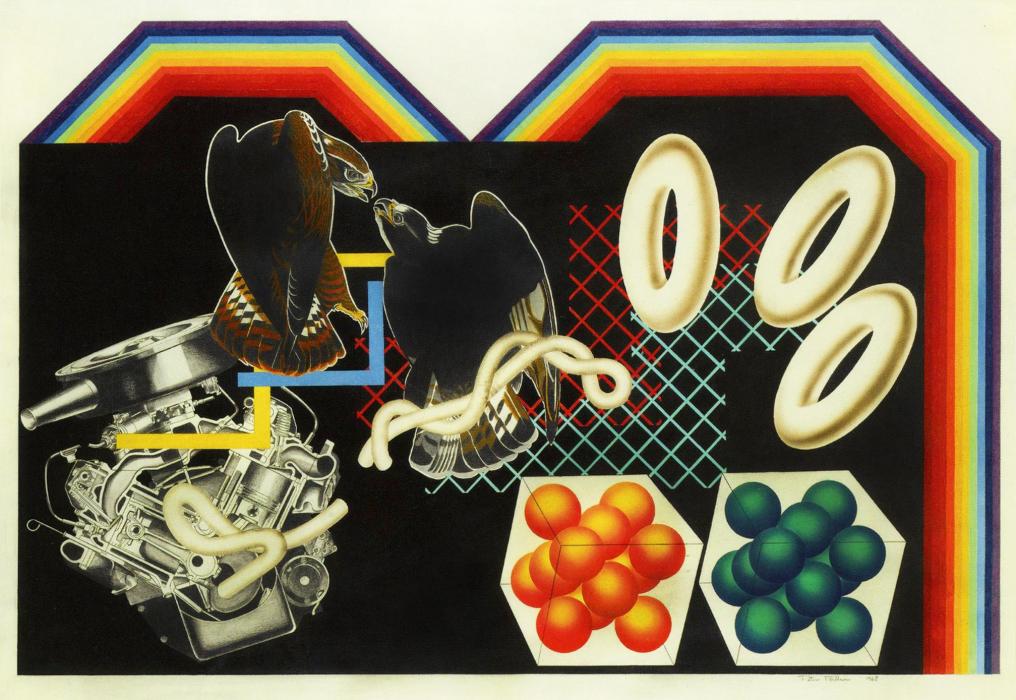

Phillips is currently working on a reimagining of his work Hybrid, originally created in 1966. This project saw Phillips, in partnership with Gerald Laing, interview the general public about their preferences in art, before working with a computer scientist at IBM to analyse the results. A large sculpture emerged from this collaborative project back then. Hybrid 2.0, in its early stages, promises to be quite a feat, producing algorithms through digital means, with its eventual presentation and medium yet to be decided.

This interview took place at the Tinbeerwah property with Zoe and Read also participating. Phillips, a reluctant interviewee for his entire career, remained a reserved presence, although still capable of a succinct turn of phrase.

‘It's fun to paint,’ he says, ‘You get a new experience every minute as you're slopping the paint on one way or another.'

Barnaby: I wanted to start by listing some of the cities you’ve lived in over the years, for you to comment on your fondest memories, the art community and overall impressions of each. Firstly, Zurich.

Peter: Is Zurich trendy? Zurichers think it's trendy, but I don't. I went there because of my wife and my dealer Bruno Bischofberger. It was a good place. The art scene was alright.

Zoe: You did a lot of partying in Zurich.

Barnaby: You were born in Birmingham [in 1939]. What did your parents do?

Peter: My father was a carpenter and a builder. My mother worked at Cadbury's. Birmingham was fine when I was young. I went to school at Moseley Road Art School, got my diploma in art at Birmingham School of Art, then went to the Royal College of Art in London.

Read: You grew up in a planned community called Bournville, which was created by the Cadbury family, a Quaker family who set this community up on Quaker ideals.

Peter: Good guys, Quakers.

Read: When you were at Moseley Road Art School you won a scholarship that allowed you to backpack around Italy, so suddenly you were seeing all this art. In terms of the formative things that made you who you are, you’ve always spoken of Moseley Road, backpacking around Europe and going to Florence for the first time and seeing real art.

Peter: I filled my backpack with Murano glassware as presents for my mother and father. I had a backpack full of glass when I came home. It was a big step for a kid from Birmingham to be given money to go and look at real art. They had real art in Birmingham too, but they didn't cultivate it very well. After all, all the Pre-Raphaelites were from there.

Barnaby: And London?

Peter: Well London's a big place isn't it? So what can you say about London? One has a good time in London. I was living in a house on Holland Road. All the people who lived around me were students and crooks and it was great. I could work. And everyone thought I was a nutcase.

Barnaby: And while living in New York on a Harkness Scholarship in 1964, you drove across America with Allen Jones.

Peter: I took him with me. I had the money and the car.

Barnaby: You stayed with Dennis Hopper on that trip. What did you get up to with him?

Peter: I didn't get up to anything with Dennis Hopper, thank you very much! We met a lot of people, and we went to the places people went in those days. Crazy people. Certainly crazier in Los Angeles than they were in New York—and it was the real Los Angeles in those days. I think Harkness had other ideas in mind rather than me visiting crazy Dennis Hopper in Los Angeles.

Zoe: You always speak fondly of New York, because the artists were more open than they were in England.

Peter: Roy Lichtenstein was a good friend there. People were friendly in the arts scene, though it's probably different now.

Barnaby: Another Harkness recipient was Brett Whiteley, perhaps a couple of years after you. But did you cross paths with him in London beforehand?

Peter: He was always everywhere. He lived round the corner from me in London, but he was Australian and we didn't have that much in common, he was doing his own thing. He had a scholarship from over here and he certainly seemed well off—he had paper I couldn't afford and an apartment I couldn't afford. A typical Aussie with a lot of money. He gets pushed and pushed as if he's the only artist Australia has ever had, but there are thousands who haven’t been pushed. And I don't know why they push Whiteley, to be honest.

Barnaby: You were featured in Ken Russell's famous documentary film Pop Goes The Easel (1962). What did that do for your career?

Peter: I don't know, but it was a lot of fun. Ken Russell was on to pop art very early, he liked to be in front of everything, and he was in front of a lot of things in those days. You don't turn down opportunities like that when you're young and inexperienced. He was a nice guy to work with.

Barnaby: What aesthetics, artistic values, even morals, did you share with the likes of Hockney, Blake, Boshier and others?

Peter: We were just in the same place at the same time, when everybody was shouting at us for being irrelevant when we were at the Royal College, which was very conservative at the time.

Barnaby: You never had a problem with the pop art label?

Peter: Why should I? It didn't bother me, it was what it was. Why make it out to be something else just because everybody thought pop art was not high art? For me it was high art, and much more visual than a lot of high art. I went my own way, which was mixing in with the people who were more real for me, people in books and magazines. David Hockney used to declare 'I am not a pop artist'; he was shouting that at some point.

Barnaby: You two had a good relationship?

Peter: He's the king of the castle. I'm the tough guy.

Barnaby: Politics has always been distasteful to you, hasn’t it?

Peter: I never believed in politics, still don’t. Let's change the subject.

Zoe: He might not admit it, but I think there's a lot of political commentary in his paintings, throughout his career, and especially in the paintings he made during the second war in Iraq. There is a lot of military imagery in that work.

Peter: I was born during the war as the bombs were dropping on Birmingham, which they did occasionally, blowing up houses where people lived. You don't take it lightly, it goes into your body. I get upset even now when I think about it. Anybody who has lived through any part of war will know its horror. So many other people went through it too, so that as so-called pop artists, we were on to a lighter subject.

Barnaby: I understand you are a big fan of science fiction novels. Has that a bearing on your art at all?

Peter: Science fiction writers are really intelligent, and back in the 1950s and 60s it was really original. Comics too: when I was young, my aunty, who lived in South Africa, used to send all these comic books to my other aunties in London. All these rolled up comic strips I still have, they're probably quite valuable now.

Read: Peter is very technically minded, and a focus on technological advancement is obviously prominent in science fiction. To combine that with art is probably not something he did on a conscious level, but it must have been a factor on a subconscious level. Peter has long leveraged technology in a way that very few of his contemporaries have; he was one of the first of his generation to adopt it. Something like Hybrid is a perfect example—to combine art and technology like that in the mid-1960s would have been unheard of. Nowadays you think of it as being quite normal. Since the early 2000s he has been using a Cintiq, a massive Wacom tablet from before the dawn of touchscreen technology. You use it to draw with a special pen. He is self-taught and has always taken to new technology easily.

Peter: Why do it the hard way when there's an easier way? You can sit there and draw and it can take you three days, or you can do it in half an hour on a computer.

Barnaby: How is life in Tinbeerwah generally?

Read: Up until a few months ago Peter smoked two or three packs of cigarettes a day. During the first 60 days of quitting we wouldn't have been doing this interview.

Peter: I'd be killing you.

Read: Peter is notoriously reclusive compared to some of his old peers. We just had an email from Derek Boshier who sent photos of him having dinner with Peter Blake and David Hockney. They still catch up.

Zoe: Even if you lived in London you wouldn't be doing that.

Barnaby: Is living round here conducive to the type of art you make?

Peter: Not at all, but it's peaceful, more or less, and that's what everyone wants.

Thanks to Zoe Phillips-Price and Lauren Burgeson.