THARUNKA to THOR – Journalism, Politics and Art 1970–1973

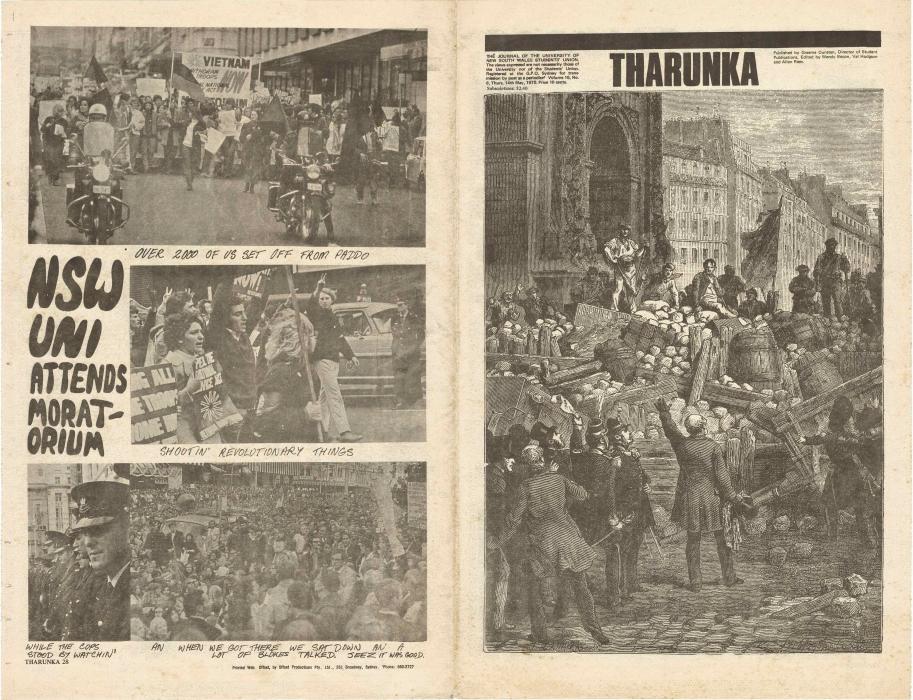

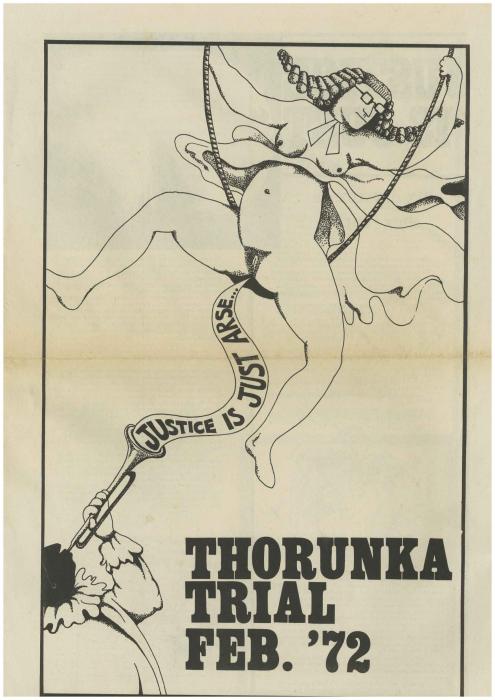

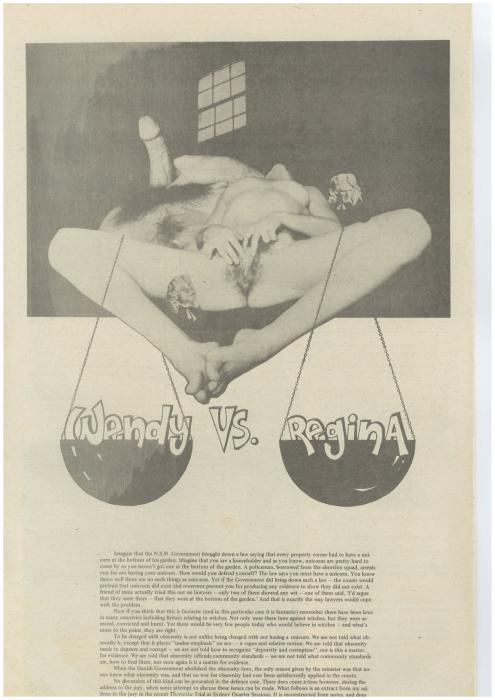

The following conversation with Wendy Bacon and Chris Nash took place on 11th of May 2017 at Frontyard Projects in Marrickville, Sydney. Installed in the windows of the common room of Frontyard Projects—a Not-Only-Artist-Run Initiative and Residency—were a series of excerpts of the UNSW student newspaper THARUNKA and its later underground iterations THORUNKA and THOR printed in black and red ink on sheets of transparent acrylic,—an echo of the transparency for which the publications had called. The prints re-present wide-ranging issues: Aboriginal land rights, the war in Vietnam, women’s and gay liberation and the violence of the criminal justice system. These campaigns and critiques sit alongside images of the body and sex acts, in opposition to the draconian censorship regime in Australia at that time, and to ultimately question why such imagery was deemed obscene when state-sanctioned violence was not. The publications in their varied forms were subject to over 40 summonses between 1970–73, for their allegedly obscene and indecent content. Wendy, together with fellow editor John Cox, was held in prison on remand on two occasions for several weeks as a result. The trial saw a shift in censorship law with most of the charges being dropped.

Wendy continues to be involved in political activism and investigative journalism; she is the contributing editor of New Matilda. Chris is the Foundation Professor of Journalism at Monash University and has recently published a book that discusses the relationship between art and journalism, What is Journalism? The Art and Politics of a Rupture.

After discovering an archive of Tharunka journals in a trunk at their home, Wendy and Chris curated an exhibition at 107 Projects, Redfern and later at Frontyard Projects, Marrickville, along with a series of forums and talks considering the social and political context of the publications and their ongoing significance.

Tilly Glascodine (TG): So there was Thorout, Tharanka, Thoranka and then Thor. How did Thorout first come about as an independent publication?

Wendy Bacon (WB): Yes so there were four different publications with two other single issues, so six in total. In late 1969, a group of students at UNSW, who were a mixture of broadly anarchist and left Labor club people, decided to hold a meeting and debate whether the Student Union Council was a worthwhile institution. This led to a vote and the Council was actually abolished for a short time. From the perspective of today, this idea might seem quite farcical. But you need to see this in the context of the challenge to the way universities were organised at the time. Students were demanding a say in their education. We were influenced at the time by the Situationists, an anti-authoritarian movement in France that were inspired by avant-garde artistic movements including Dadaism and anti-authoritarian critiques of capitalism. Over the decades, much of the detail had dropped away but I dipped back into the newspapers and old papers and quickly remembered our mood and actions more clearly. I could see where we were coming from!

While the Student Council was abolished, we published two independent newspapers called Thorout that we distributed on the campus. Then the Student Council was reinstated and we had so enjoyed putting out the publications that we (Wendy Bacon and fellow editors Val Hodgson and Allan Rees) applied to become editors of the student publication Tharunka. This of course was a big contradiction seeing as we were amongst those who had abolished the Student Union Council! All I can say to this is that we thought if we had a newspaper, we could publish what we wanted which would be a lot of fun and stir up a lot of trouble! Our student group then developed into a broader group of people beyond the university such as those involved with the Sydney libertarian push including artists like Jenny Coopes and writers such as Frank Moorhouse. It was far more of an open situation than you would have today with a student newspaper, and that was because there weren’t the same opportunities for independent publications. There was a huge amount of self-censorship and censorship in Australia and a lot of us were really ready to challenge that.

Amy Parker (AP): How did Tharunka then evolve in Thorunka and later Thor, were these adaptations in response to the summonses and arrests over ‘obscene’ content?

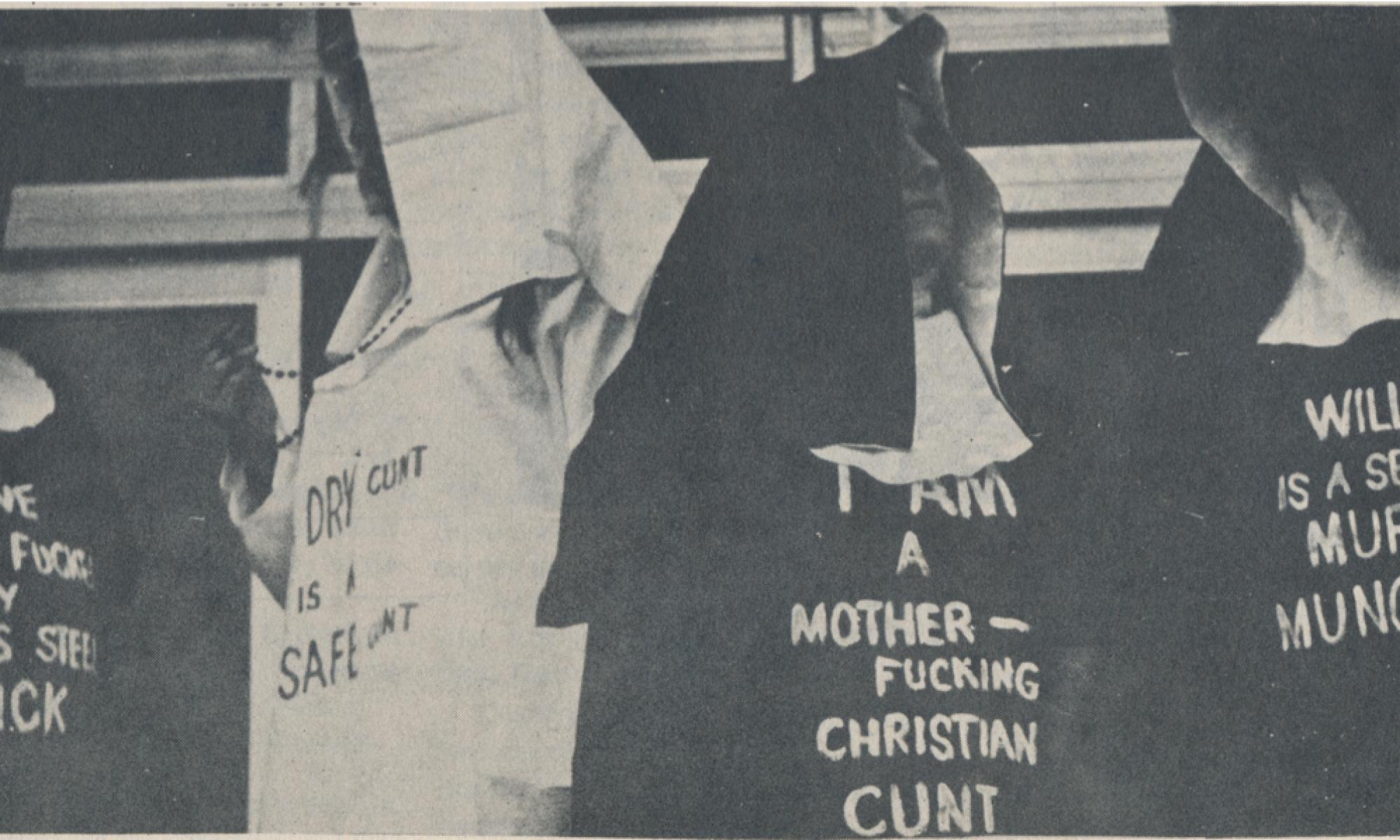

WB: The Tharunka edition that led to the charges was one that had a naked student on a cross on the cover and the poem Cunt is a Christian Word inside. Already conservative politicians and media had been calling for us to be charged. At the time, we were told that sermons were being preached at churches around Sydney pushing the government to act against us. Val and Graeme appeared in court in August 1970. We considered how to respond and decided to scale up our censorship battle by taking the protest right into the heart of the court system. We sewed nun's costumes with slogans from the poem Cunt is a Christian Word disguised by bibs on the front. A group of five of us wore them into the court vestibule and removed the bibs revealing the slogans. We handed out copies of the poem to scores of members of the public waiting inside the court. It was at this stage that I was arrested and charged with exhibiting an obscene publication (the costume with the slogan) and distributing an obscene publication (the pamphlet with the poem).

AP: Which one were you?!

WB: I’m the one on the left hand side with the slogan, ‘I have been fucked by God’s steel prick.’ I think today you might call our protest performance art but given that we hadn't heard of that term then, it would seem a bit pretentious to call it that now. Our protest was meant to show our rejection of the legitimacy of the court's power to decide what was obscene and what was not, what we could or couldn't publish.

AP: Do you know who wrote the poem Cunt is a Christian Word?

WB: To tell you the truth I don't even know. Like a lot of other material, we took it from an underground publication from the United States.

AP: Can you describe how this content circulated amongst aligned publications?

WB: We generated a lot of our own material but also freely selected from international left-wing publications. Copyright didn’t exist for us! We saw our task as to get the information out to as wide an audience as possible. It didn't occur to us to contact the publishers because we assumed they would want the word spread. For example, Youth International Party activist, Jerry Rubin had published a book 'Do It! Scenarios of the Revolution’ that was initially banned in Australia. The book was full of ideas about creative protests and how to resist the state. It was a very full on critique of the capitalist system. So we serialised the whole of that book in four page inserts, first in Tharunka and then in Thorunka.

AP: Back to the two obscenity trials, I’m interested in how you rejected the very legitimacy of these laws and the basis of your defence that resulted in the charges being dropped?

WB: I argued that the legal notion of obscenity was based on ideas about depravity and corruption for which there was no evidence. I was trying to convince the jury that innate notions of evil were a social construct and to some extent I was successful. In that case, the jury acquitted me of handing out the pamphlet and convicted me of publishing the slogan on the front of the nun’s costume. In the first case, I refused to use the defence of literary merit, which was the only one available, because I saw it as elitist. We were not arguing that students or readers of Tharunka were a special group who should gain special access to this material. Rather we wanted everyone to have access. This set our approach apart from that taken by others who argued that artistic work should be treated differently.

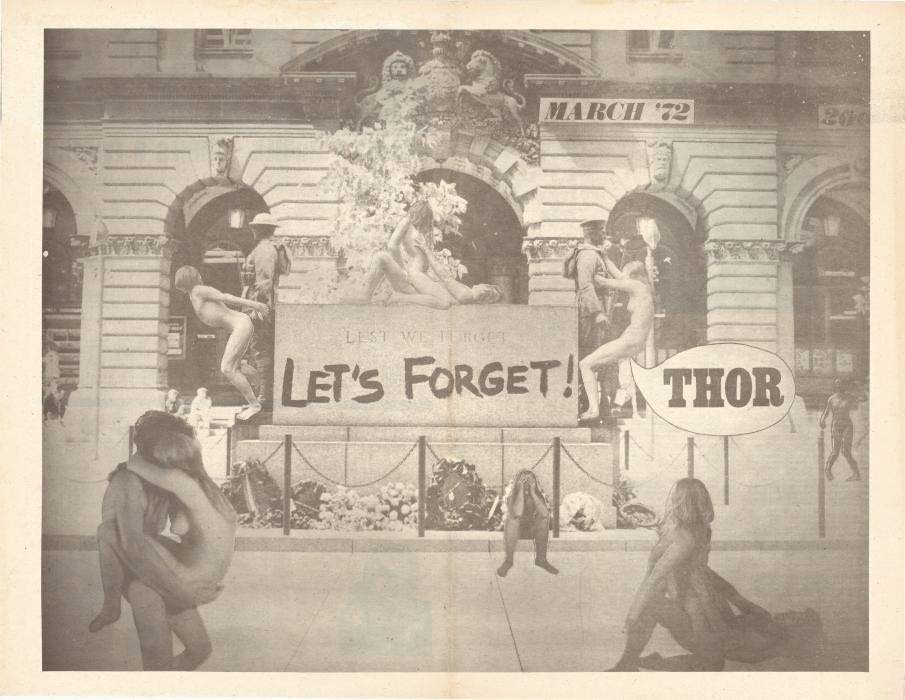

TG: The use of erotic or obscene art was such an important part of the paper and I am interested in how you used the notion of sexual obscenity to juxtapose the very real obscenities of war and oppression that were going on around you at that time. For example, the image of the American soldier holding the body of a dead man positioned next to the naked couple...

WB: We, ourselves, like many thousands then opposing Australia's intervention in the Vietnam War, found the human suffering deeply offensive while the state sanctioned it or covered it up. To explain why one group might find something obscene and another not, we were arguing that you had to unpack the social and political relations rather than to refer to innate notions of morality.

TG: It seems like the government was using the focus of sex and sexuality as obscene as a decoy from everything else that was going on… such as continuing colonisation and war. It’s powerful that you were framing sexuality as this positive, normal thing.

WB: Yes. One of the points that we were making is that obscenity is a subjective notion and laws around censorship are used by governments to impose a certain sort of behaviour or morality onto people. At the same time as those in power wanted to repress the expression of sexuality, they promoted violence and war. Our vision was for a far more cooperative and anti-authoritarian society.

The visual design was a very important part of the publications. We used montage that combined photographed images, images taken from existing publications with ink drawings. For example, we superimposed images of naked bodies in sexual poses onto an image of the War Cenotaph in Martin Place. Key designers were Wallace Randolf who was also a stage set designer and poet, Val Hodgson, who was then an architecture student at UNSW and organised the layout of the newspapers as well as doing many pages herself and Jenny Coopes who designed pages and did black and white ink drawings.

TG: Chris, even though you weren’t directly involved in Tharunka at the time, this show was put on very much as a collaboration between yourself and Wendy. What was the inspiration for putting on this show together almost 40 years later?

Chris Nash (CN): We had a long break [from teaching] and we spent about four or five weeks of that period in North America, with about a week in New York where we happened to visit the Whitney Museum. We walked into the Whitney and on the third floor in their New Acquisitions Gallery was a work by Hans Haacke that consisted of a whole lot of printed pages, which were about the real estate holdings of a man named Shapolsky. He had diagrams with lines connecting different companies and intersecting ownership patterns and indicating where the money was coming from. We discovered that this work had been proposed for an exhibition at the Guggenheim in 1971 and it had been cancelled six days before it started on the basis that then director [Thomas Messer] had said this is not art, this is photojournalism. And we were in agreement, it was journalism, but it was, of course, also art and the Whitney had recognised that long after the event. My question was: Is it also journalism and, if so, what is journalism? Can journalism be art? I was particularly interested, as an academic, in the issue of if journalism can be art, what is journalism as a research discipline and in that context, if journalism is art what are the consequences of that? How do all of these things fit together?

AP: It is interesting how you curated this material into an exhibition format at both Frontyard Projects and previously at 107 Projects. Why did you choose to re-present these publications in an art context? Can you speak to the relationship of art and journalism and why you’ve re-framed the publications within these artist-run spaces?

CN: We decided we would do the exhibition of the Tharunkas and we would do it in an art gallery, because we had come across 107 Projects and we liked what they were doing, however, we would actually draw out the whole theoretical debate about journalism and art and not just do a nostalgia trip. We wanted to try and interpret in the larger context of its time what was happening in the art world in respect to journalism, and then secondly what are the consequences for contemporary issues about journalism and art.

TG: A correlation I notice between Tharunka and Haacke is a kind of comparison of morals. I read about a work of Haacke’s, after you mentioned him Chris, where he shows the inadequacy of art institutions' stance as being ‘moral’ or ‘good’ by positioning the facts surrounding the galleries within them. He did a poll at MoMA where he asked visitors whether they would vote for Governor Rockefeller, who was on the board of MoMA, because of his stance on the Vietnam War—and the clear majority of people who voted said they wouldn’t. It showed how politicians could use their proximity to the gallery as a way of gaining moral capital. I feel like Tharunka took similar action. They both show the hypocrisy of their opponent’s position by doing this really simple gesture of putting contradictory things next to each other.

CN: What Haacke is arguing—and what Tharunka was arguing too, because Tharunka rejected the literary defence for as long as they could (eventually they played it in a very minor way)—was not that there are privileged elite audiences who should be able to read this and they won’t be affected by the sexual content;—they were saying the sexual content should be available to all, and that people can make of it what they will. So it was an anti-elitist position and it was a thoroughly libertarian position, that this content should be available to all and this definition of obscenity is a ridiculous concept of very conservative social forces and we are here to blow it apart, which they did. So that is exactly the same as what Haacke did in the sense, and this is what you’re saying I think, that it’s the banality of fact; we are just putting this out there and it is your reaction to what we’ve done that will going to create the meaning. There were some works by Haacke during the 1970s where he was getting stuck into Mobil, Phillips and British Leyland about their relations with the apartheid regime in South Africa. In several works he quoted statements by company executives from Mobil and other companies, declaring that sponsorship for art is a ‘no brainer’ for corporations because you just buy good will and it’s a business decision, it’s not an art decision, it’s not a cultural decision, it’s not a moral decision. So Haacke had artworks in a show about what was happening in South Africa at the time alongside quoted statements by these guys and actually there is a photograph of the head of Mobil standing next to one of those art works.

So from the point of view of art, the basic argument is that Tharunka, Thor and Thorunka revealed a set of power relations and then actually intervened in those power relations, and the totality of those relations and events is what constitutes the artwork.

TG: And moral relations...

CN: Yes! Social, political moral etc. All of those things, what is good, what is bad, who has the power to determine this etc. That is all revealed in the response. The art object itself is banal.

Art is not an object; it’s a practice. It’s not just an event or a project; it's something that happens, which has consequences, and the consequences are just as important as the object or event, and that’s where the politics lie. And that’s what Haacke and Tharunka, Thor and Thorunka all share in common.