'This is our time'

Dale Harding is a Brisbane based artist and a descendant of the Bidjara, Ghungalu, and Garingbal peoples of Central Queensland. Harding grew up in the Queensland coal mining community of Moranbah—his father a miner and cattle farmer and his mother a skilled artisan. Harding’s painterly and sculptural practice is driven by his deep connection with the experiences and histories of his family—in particular, his matrilineal heritage—and the important stories of what is now known as Carnarvon Gorge, a nearly 20 mile long canyon of sandstone cliffs and remnant rainforest that sits among the headwaters of various river systems in Queensland’s Central Highlands. Harding graduated from the Queensland College of Art in 2013 and since then has exhibited widely, including GOMA Q, Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane (2015); White Collared, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane (2015); the 11th Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju, South Korea (2016); documenta 14, Kassel, Germany and Athens, Greece (2017); the 10th Liverpool Biennial, Liverpool, United Kingdom (2018); and most recently in From Will to Form, the 2018 TarraWarra Biennial at the TarraWarra Museum of Art. In this discussion, Dale Harding talks with Tim Riley Walsh about recent shifts in his practice, reflecting particularly on his ongoing series of wall paintings, as well as discussing future projects at the Institute of Modern Art.

Tim Riley Walsh: I wanted to begin with a reflection on something you said to me in an email recently that I feel touches very strongly on a shift in your practice that began with to cast a bright shadow, your 2017 solo show at Milani Gallery, Brisbane. These seemed to be sentiments that were coalescing around the time of your inclusion the same year in documenta 14—which is not to say it was a reaction to that important show, but rather just a way to place these thoughts in a context. What struck me especially was that you felt that ‘presenting Indigenous suffering had begun to feel like a convention’ to you, ‘beyond historical redress’ and in light of the investigation of ‘urgent histories of abuse and suffering of previous generations in [your earlier] work’ it was time to offer yourself ‘some notes to future bodies of work in to cast a bright shadow.’ Can you talk more about this insight for you with this particular body of work and what impact it had on your practice since that point?

Dale Harding: Well, really, there are many things. I think I also mentioned escaping from the political arenas of contemporary art. I needed some time away from the urgent histories of previous generations. I just needed some time out and at that point, I didn’t quite know what I was doing but I knew it was necessary to do one thing—just to be in the work. When I say the work, the work was an urgent and pressing consolidation on a personal front. What was pressing was digesting and making sense of where I was at. Among that, I was seduced by painting in documenta and in Europe. I’ve used that word since—seduced—as I really was seduced away from my attention to sculptural practices by painting. What was beautiful to me was paint. I saw paintings address for me the same kind of content I was interested in, but the forms of painting I discovered abroad was where it was at. Potent and relevant content was beautiful in paint and poetry.

TRW: Finding your way through beauty: was this shift driven by more of an aesthetic consideration—was this you trying to engage with the viewer in a different way than you had previously?

DH: Prior to to cast a bright shadow, I was making the work on behalf of myself and my family—I had other people to think about in previous motivations for making. But in this new body of work it was just for me, work I wanted to make for myself. I was spending a lot of time at home. Really that body of work came from there—the whole store at home, the library and gathered resources—it all came from my house. It was all there—I just hadn’t seen the forest for the trees. The whole show emerged from that house after I took time to reflect on recent experiences and remember what I always had with me. I’ve learnt and remembered a lot of things that are important to my intents.

TRW: You also described in this same conversation, as you mentioned just before, a ‘longing to return from the political arenas of contemporary art’—what part do you feel politics plays in your art? How does your practice allow for an important, broader articulation of your own selfhood and your family’s cultures?

DH: Politicking had weighed down my making. Performing politicking and creating politics had weighed down my making. And, politics within a cultural format is really necessary, to understand and know these things is key to the continuation of culture. Politics comes from a very necessary place. To develop knowledge and skill within political functions is part of my family’s culture. Maintaining our family and cultural structures means learning how to be amongst process and knowing your own and your collective politics. Politicking is where politics becomes the campaigns and the ego-drives.

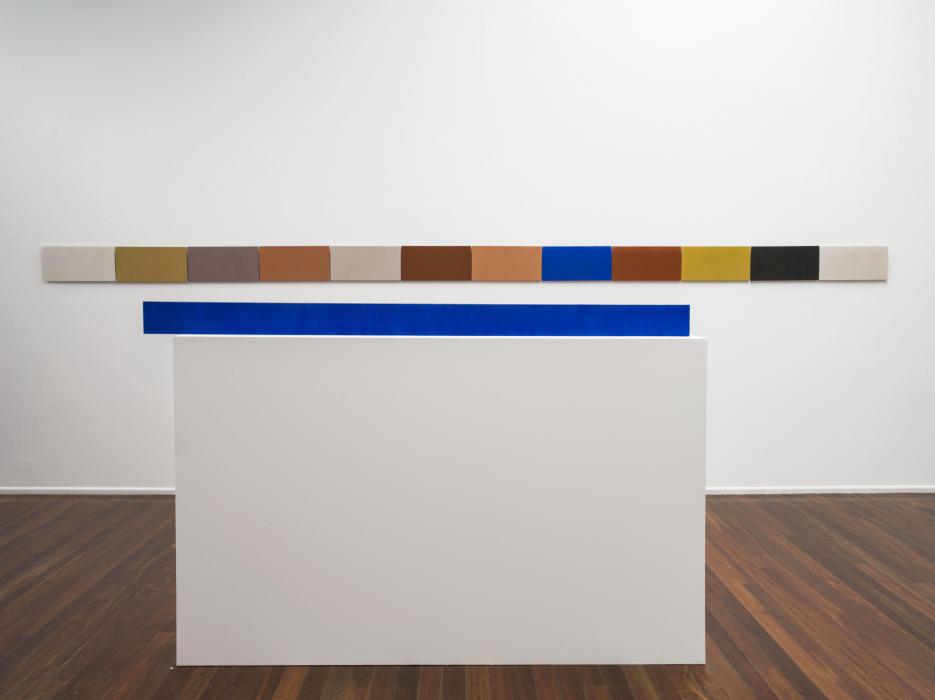

TRW: This maintenance of familial and cultural structures comes across very strongly in your wall paintings. With Wall Compositions from Memory (2018) in the TarraWarra Biennial, you are acknowledging over four years of a series of paintings made by yourself and your extended family in a number of pretty extraordinary places: beginning with black days in the Dawson River country (2014) in Outlaws at the Linden Centre for Contemporary Arts, St Kilda, to the Gwangju Biennale’s Exhibition Hall, Kassel’s Naturkundemuseum im Ottoneum for documenta 14, the Tate Liverpool as part of the Liverpool Biennial, and as a permanent commission in the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art’s recent rehang of their Australian Art collection—amongst other locales. How has this method evolved over time materially and conceptually? What does this contextual shift of space—from sandstone cliff to gallery wall—mean for you and your family?

DH: A tangible, visible evolution of the conceptual process is that now my cousin, Jordan Upkett, and others in my family, are informed and prepared to be able to do this work in their own lives. In addition to Uncle Milton Lawton and Will Lawton in The National: New Australian Art, Sydney (2017), and my mum Kate and I in Gwangju—the depth of understanding on a muscle memory level in my families, across generations, is normal—in ways that weren’t present at the time of the first wall painting in 2014 in Outlaws. With the Liverpool work, the use of plinths as worktops and platforms in the processes of painting says something about how this space was inhabited. I wasn’t looking to critique or subvert the Tate Liverpool, but I didn’t uphold the same careful reverence for the white cube that I held previously. It was the act of being in the space and doing whatever I could to tell stories. What is available to you as a contemporary maker in that locality that is immediately relevant. My environment includes art galleries.

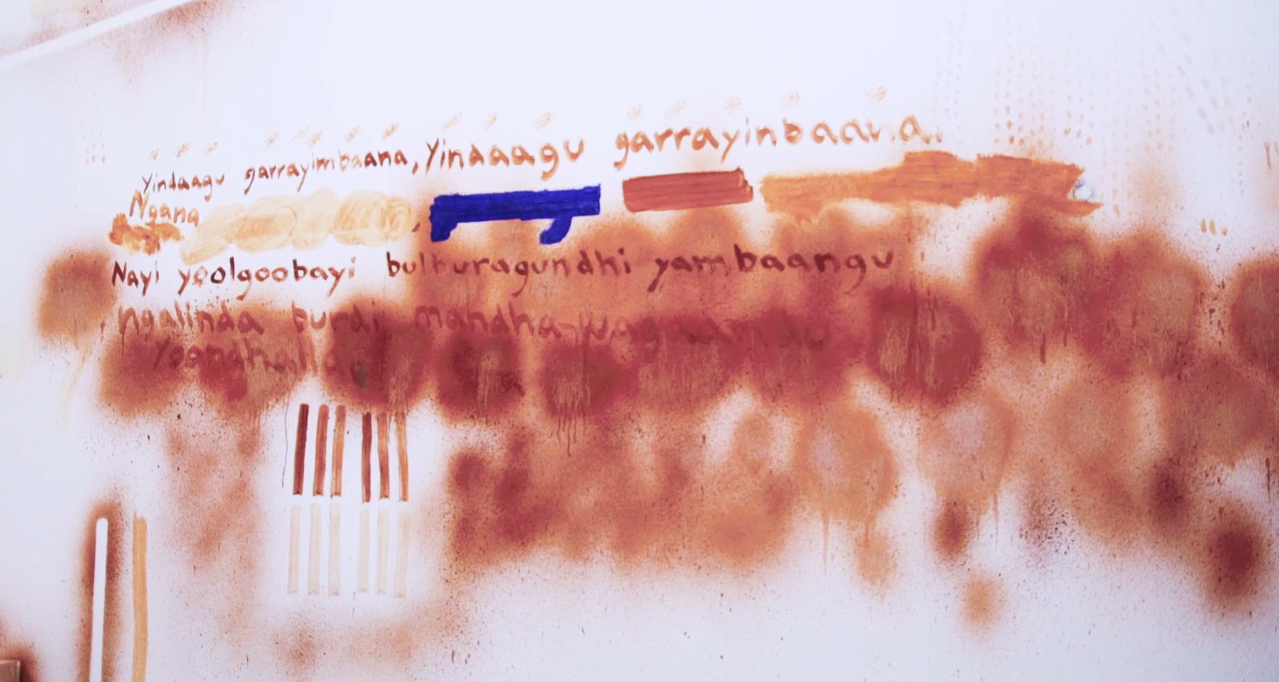

TRW: With the two latest wall paintings at TarraWarra and Liverpool, there seems to be this confident flow that is happening—they feel looser and more liquid. In Wall Compositions from Memory, I see this in those square shapes of rubbed washes of red ochre. In Wall Compositions in Bimbird and Reckitt’s Blue (2018) in Liverpool, it’s in the mingling of that powerful blue and ochre over and amongst each other, the drips and smears. How was the experience of making both of these?

DH: There are very different parts of myself and intent in those two works. In Liverpool, the smears were about the tasks of washing, scrubbing—as well as staining and removing stains simultaneously. It came from The Source (Well head) (2017)—a large work on raw linen where I put Reckitt’s Blue into a calico bag, got on my hands and knees and handwashed the Blue into the fabric to accumulate the image.[1] Ideas of performing that same menial task carried over into the Reckitt’s Blue and the earth pigments used in Liverpool. Using earth pigments and Reckitt’s Blue left traces of working through the histories I was in contact with in that setting. In TarraWarra, there was a different intent. Jordan, who collaborated with me on this work and I were empowered by the histories we were in contact with—in constructive ways. For the Liverpool work, I was trying to make sense of these histories. The TarraWarra work was trying to be in touch with and build what we inherit as Murris. Through remembering our inheritance and looking into our own lives. Sharing the time and space as cultural people is crucial to what remained visible in both ‘artworks’ that make up our contribution to From Will To Form.

TRW: In terms of colour palette, the emergence of your use of bright yellow from your recent time in Stockholm, as part of the Iaspis residency program, also strikes me as important—particularly in the work As I remember it (2018). Can you speak a little about this? Is this something that will be more visible in your third solo show at Milani Gallery in November?

DH: As I remember it is currently a two by seventeen metre painting made on multiple drops of paper which I lined the Iaspis studio with. That yellow was a discounted dry pigment available in bulk in the art supplies store near the studio—it was old stock. I was there to learn and experiment and try things without consequence. The yellow pigment and some yellow Chinese ink were cheap and readily available in the place of ochre here at home. In addition to that, it has great relevance. The Xanthorrhoea family offers particular relevance to golden and yellow tones in previous work, and initial research showed parallels in Scandinavia with a particular lichen used historically for the same colour grouped as Xanthoria. [2] It was a way for me to place my sensibilities among local practice and materials. It comes back to that sense of immediacy and looking at your surroundings. I inherit and believe that Aboriginal peoples tell largely the same story, but the local environment and re The Source (Well head)s inform shifts in expression. The work that I made on residency in Stockholm is central to the install of new work at Milani Gallery in November and to my proposals to future cultural inheritances.

TRW: How does language function in your work—like the text visible in the Liverpool piece—and when you discuss your practice publicly? There is this beautiful consideration and expression in your spoken words, which to me feels like a very important part of your life and practice.

DH: I always like to acknowledge Christian Thompson’s work in keeping visible and growing Bidjara language. It was very important to me to embed language in the work in Liverpool. In my absence, the language of that ochre and those stories could resonate. When speaking or writing about my work publicly—it comes back to getting the story right. That can be applied in many ways. The story of preparing ochre. The story of applying ochre. And then the story of why you did it. I’ve found my work and my personal life have benefitted from consciousness in languages—visual languages, unspoken languages, academic languages, colloquial languages, Murri-way, Migaloo-way. There are multiple languages that I can inhabit to tell a story.

TRW: To conclude, are you able to tell us a little about your upcoming solo show at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane in early 2019? Will this be a survey of sorts or predominantly new work?

DH: The show is about returning to Brisbane and sharing work and conversations I’ve been a part of in other places. To bring them back here, to share them here. There will be new iterations of previous wall paintings and installations, as well as looking to futures in my own practice and our communities. I wrote into the work in Kassel ‘we did not inherit mediocrity; this is our time’ as an urgent reminder to cultural continuum.

At the time of publication of this interview, Dale Harding’s solo show The Drive Home had recently opened at Milani Gallery, Brisbane, running from 3–24 November 2018. Harding’s upcoming survey exhibition Current Iterations at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane will run from 9 February–30 March 2019.

[1] Reckitt’s Blue is a laundry whitening agent developed in the mid-19th century by the British company Reckitt & Colman. It is made from powdered ultramarine and baking soda and comes packaged as a condensed cube. It was used domestically across the colonial frontier. Harding’s grandmother and great-grandmother worked as domestic servants under the auspices of the Queensland Government’s Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act of 1897. This same Blue was also used in some cases by Harding’s matrilineal ancestors to decorate shields.

[2] Xanthorrhoea or ‘grass tree’ resin has been used for tens of thousands of years as a cultural medium on the continent of Australia, and Harding continues this tradition through his use of this golden brown resin in a number of recent works, such as Moonda and The Shame Fella (2018), The boys (2018), and Blackboy (2017). There is also a golden quality to the dried fronds of the tree. The plant’s name is derived from Ancient Greek’s xanthós (yellow, golden), linking the Xanthoria lichen and Xanthorrhoea tree, native to two very different eco-systems, through their shared hue and linguistic connections.

-itok=L1l0FrKV.jpg)

-itok=L94IpeKH.jpg)