Inside out: an artist’s view of documenta 14

Tessa: We've had radically different experiences of documenta 14. As an exhibiting artist, you visited both sites several times before the exhibition. This seems both diligent and luxurious! As a viewer on a limited time schedule, I rushed around Athens and Kassel, missing key works and in particular, public events. While I cursed the often opaque signage and printed material for not delivering me a quick glance ‘hit list’, I cursed myself more for not allowing the time for the important ideas to unfold. Nevertheless, there were still key concepts, and points of connection, that made themselves felt. I wonder if together, we could unpack some of what documenta 14 meant, or at the very least, what it meant to us? And to start us off, I wondered if you could talk about your experience of being invited to participate. How did it come about, and what was involved in all the stages between the invitation and exhibiting?

In January, 2016, I received a call from Josh Milani, my gallerist in Brisbane, to tell me I’d been selected to represent Australia in documenta 14 by Hendrik Folkerts who chose the Australian artists, one of a team of seven curators. Some weeks later I received a letter from Adam Szymczyk, Artistic Director, formally inviting me to participate, along with 163 other artists. Hendrik selected my artwork because of, he wrote, its rigour and its socio-political content. He appreciated my forensic deployment of field research, investigating, witnessing on the ground evidence of the conceptual premises underlying my artworks.

Adam invited me to come to Athens and Kassel in April, 2016 to meet the documenta team and familiarise myself with the contexts of the two cities to inform my practice. He planned a multi-vocal, global event addressing current political situations. After my first research trip there, environmental issues emerged as the theme for Athens. The evolving outcome, Plastikus Progressus, addresses the pollution of the trans-ecology of water with plastic litter. The trauma of war evolved as the conceptual focus for Kassel with the installation, Interior Decoration. The two artworks were related to each other and to both cities, plus Sydney, under the thematic title, Momento Mori.

Plastikus Progressus is a complex installation mimicking a natural history museum display set in 2054. It’s composed of a touch screen, photographs, sound, works on paper and sculptures. The sculptures are made of litter and discarded vacuum cleaners to represent hybrid creatures, genetically engineered to consume plastic for food, and in the process, cleaning up our mess in the streets, rivers and oceans. It’s a futuristic parody.

The installation Interior Decoration, referring to the decoration of soldiers for bravery, was re-contextualised from previous iterations to refer closely to contemporary as well as historical events and issues related to trauma. On Hendrik’s suggestion, I documented memorials, artefacts, public artworks and sites around Kassel pertaining to war, and drew upon my archive of photographs of trauma and atrocities. I documented Australian war memorials and the 2017 Anzac Day March in Sydney. The imagery was collaged into a decorative dado to surround the sculptural elements—a Vickers machine gun, a watchtower and trench, the last two based on military installations documented in Israel when I followed my father’s 1941, WW2 tour of duty there. The sculptures are made from my parents’ bedroom furniture; the ‘machine gun’ is made from my mother’s Singer sewing machine and bobby pins.

When you were making field trips to Athens and Kassel, were you in close contact with any of the other artists? What was the feeling like between the participants? In particular, did you forge a relationship with the other Australian artists?

At both Athens and Kassel in April 2016 there were formal tours for the artists during the day, and lectures about the cultures, histories and politics of both cities, and a program of artists’ presentations in the evening that introduced the artists to each other. In Athens the venue was the Polytechnic where famously in 1973, the dissidents’ uprising against the military junta was centred. In 2016, accommodation previously used by dissidents at the Polytechnic was occupied by Syrian refugee families. Police are barred entry onto the grounds of the Polytechnic, a restriction dating back to the overthrow of the junta.

I’m a bit of a loner and I don’t drink alcohol, so I guess I wasn’t as engaged in socialising as much as other artists may have been. But the feeling between the participants was great—very supportive and interested in each other’s practices and ideas. The artists’ presentations and lectures about Kassel were held in the Palais Bellevue (in the room where I was to install Interior Decoration). I attended tours around the city for the artists and organised personal guided tours for my own research: Sababerg Forest to document a pristine natural environment; a tour of the Kassel Waste Water Plant; walks along the river Fulda and nearby canals and tributaries; phosphate mining— a trip to a huge mullock heap named Mont Kali near the village, Heringen, on the Werra River, a tributary of the Fulda. Also, many walks around the river, its canals, tributary, streets, parks, much like in Athens, documenting, documenting.

Gordon Hookey came along to my excursion to the Sababerg Forest which was fun. I know Gordon well because I taught him (BFA at COFA) and we catch up when I show at Milani Gallery in Brisbane, where he lives now. Gordon also shows with Milani, as does Dale Harding, the other Oz artist. Dale and I became acquainted when we met for the first time, exhibiting in Kassel.

In September 2016 a Public Program organised by documenta in Athens was held in the Parko Eleftherias, a gallery and museum at the premises of the Military Junta headquarters (1967–1974) where dissidents were imprisoned, interrogated, tortured and executed. The venue had been redesigned for documenta’s Public Program, changing the gallery into an open space filled with large, movable, oblong blocks for seating. There were great talks and presentations related to documenta’s political and cultural themes, including my workshop, State Violence / Domestic Violence: The Inter-generational Affects of PTSD as an Outcome of War. This time they were aimed at the public, not just the artists.

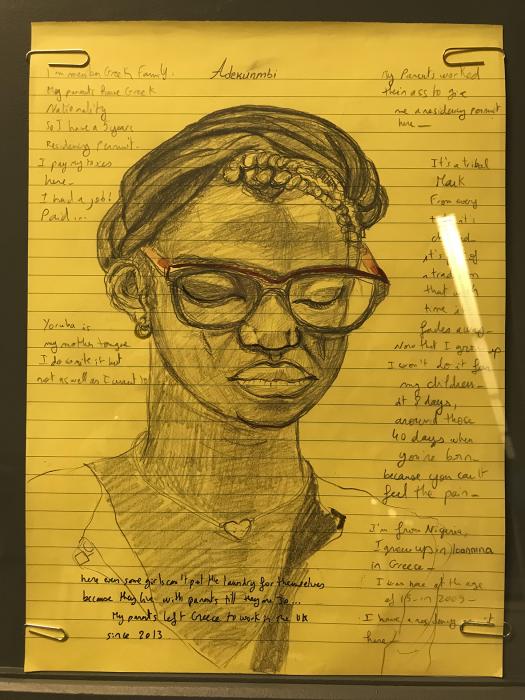

Later that month in Kassel I met up with Lebanese artist, Manoura Al Solh, who was in town researching, and she was going to be exhibiting in the space next to mine in the Palais Bellevue. Our artworks related—she was interviewing and drawing portraits of refugees from Syria and other countries who’d settled in Kassel. I was showing Interior Decoration. We kept in touch and she was one of the artists I got to know well. In the end, it turned out she exhibited elsewhere in Kassel.

I researched and documented monuments, public artworks and venues related to war, such as the Death Museum (yes there is such a thing), and the cemetery, for the dado around Interior Decoration, and returned to the Sababerg forest to photograph it in Autumn, plus plastics pollution around the Fulda River and surrounding parklands.

What was the atmosphere like among the documenta working groups and communities in the two different cities? Did you get a sense of any of the tensions surrounding the show, particularly in relation to the Athenian art community?

The documenta teams in Athens and Kassel were very efficient, friendly, very busy, but accessible. Nothing was too much trouble. There was a very focused, industrious atmosphere in the offices and on the ground—they got on well together as a team and socially.

Regarding the tensions in Athens towards documenta, in April 2016 there was talk of resentment at one end of the spectrum, and rumours of boycotts at the other extreme. A conversation with my first taxi driver went like this: the economic downturn/crisis in Greece was the fault of the EU, and now properties and businesses were selling off cheap to foreigners who were moving in, taking over. No mention of tax evasion. I, personally, was always treated with generosity, friendliness and great hospitality in Athens.

I figured Athens could only gain from documenta with the increase in tourism during the event, and Germany’s investments in the city’s cultural infrastructure, including the National Museum of Contemporary Art, which, in April 2016 hadn’t yet opened. It was an empty, cavernous series of ‘white boxes’, unused because of the economic downturn. Plus the international publicity Athens would receive as a contemporary art destination would have ongoing impact on the city’s identity. This couldn’t be a bad thing.

A program of public events leading up to documenta’s opening engaged many Greek intellectuals, academics, artists and interested public. Initially I heard the Art School was not engaged, but that changed. By the time documenta began, students were employed and gained vocational experience volunteering, plus they met and saw the work of great artists. What’s not to like? I exhibited in the Athens College of Fine Arts Gallery, which was fitted out beautifully by documenta, and the cafés on site had a never-ending stream of customers during the install and event. To a significant degree the ‘tensions’ were a beat up in the media and online.

I agree. I met some Athenian artists who were overjoyed that documenta was taking place in Athens, who were making the most of the international art traffic that otherwise simply wouldn’t have come to their city (all the more important since they couldn’t afford to travel). Of course, documenta was incredibly self-conscious and self-critical about the German-Greek dynamic, this permeated both iterations of the show. But despite the best of intentions, many Greeks continued to feel disenfranchised. Once you had installed your work, and been able to see the exhibition as a whole, what were your overarching impressions, not just of the inter-European dynamics, but of other themes, other agendas?

I did a survey from the Day Book (catalogue) of the nationalities and gender of the artists, and it seemed that approximately one in three artists were women, with a similar rate of inclusion of non-‘first world’ artists. Surprisingly, given the complaints that Greek contemporary art was not given oxygen in documenta 14, I counted 10 Greek artists versus 4 German artists.

In terms of over-arching impressions, I confess I was rather overwhelmed because my head was so full from my own art making, it was hard to come in fresh to see the other artists’ works. I couldn’t connect well with works that required lots of reading of fine detail but loved the variety and scope in the galleries, and enjoyed exploring Athens and Kassel, finding site specific works—though I didn’t get to them all.

My impression was, the curatorial thematic focused on a multifaceted investigation of ‘now’ in terms of current political, cultural and environmental awakenings, problematics, aiming for an international perspective, ‘delving into’ rather than surveying. I felt the curators were looking for artists whose practice added detail to our knowledge and perceptions of the 21st Century, not necessarily ‘stars’ as, perhaps, in previous documentas. Unlike other documentas there seemed to be fewer large-scale artworks in public spaces with some spectacular exceptions in Kassel, such as Hiwa K’s When We Were Exhaling Images (2017): steel tubes filled with personal objects, cots, lamps and books; Antonio Vega Macotela’s The Mill of Blood (2017), a giant wooden machine for making coins; and Marta Minujín’s Parthenon of Books (2017), the monolithic installation outside the Fridericianum featuring banned books donated by the public.

Did certain themes become apparent to you? Did you have favourite works?

The theme, Learning from Athens, slipped out of obscurity and into focus in relation to many of the artworks given the contexts of Greek cultural and political history in both cities. In Athens I went to the Archeological Museum, Museum of Islamic Art, the Byzantine and Christian Museum, the Acropolis and the Acropolis Museum amongst others—all great. The origins of democracy, humanism, rationalist philosophy compared to Greece’s immediate past political history—wars, invasions, dictatorships, its present economic uncertainties, gender issues, its proximity to Syria and the influx of refugees; Athens was a very provocative context for many of the works.

As an indication of how the West has ‘learnt from Athens’, Kassel is full of art and architecture derived from Classical Greek culture—marble sculptures of Greek gods line a promenade in the park along the river; a Baroque bath house is full of imagery and motifs derived from Greek art; a statue of Hercules presides over Kassel atop a water folly up on the hills above the town, et cetera.

Apart from environmental themes of which my work Plastikus Progressus was one, war and displacement, post colonialism, political protest and critique, inequalities, Indigenous rights, the aftermath of war, cultural identity, traditional knowledges, critiques of hegemonic histories, the celebration and performance of cultural riches and social mores, were themes threading through the exhibitions.

I had so many favourite works. In Athens, Mounira Al Solh’s work Spervira in the Museum of Islamic Art was very affecting—the embroidered, personal stories of Syrian refugees inside a tent, also embroidered by Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Placed within the Museum’s rich Islamic artefacts, this work was a personal insight into the devastation of war in the Middle East currently, and the huge intellectual and cultural contributions to world knowledge of Islamic countries.

On a similar theme, Indigenous Canadian artist Rebecca Belmore’s Biinjiya'iing Onji (From inside), is a site specific, beautifully carved marble tent placed near the Hill of the Muses, overlooking the Acropolis with obvious implications—stunningly intimate and corporeal, it isn’t as over determined conceptually as one might think.

Australian Indigenous artist Dale Harding’s floppy black, rubbery Aboriginal weapons and tools—boomerangs, spears, digging sticks, etc.—droop over the edge of large, stark white gallery plinths. These phallic forms are a powerfully complex expression of displacement, disempowerment, and impotence.

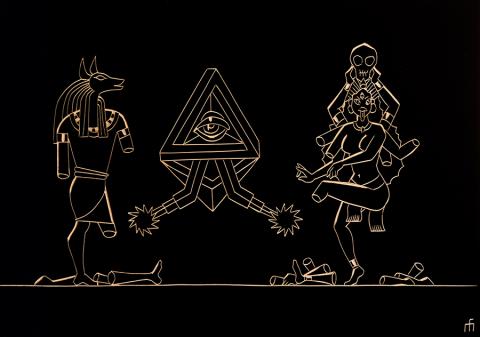

Perhaps most importantly I saw Haitian choreographer, Kettly Noel’s performance and installation, Zombification, a poetic evocation of slavery and all that implies. The installation’s components are clumps of bamboo poles surrounded by rocks, from which long, skinny puppets hang. Performer/dancers in mechanical motion enact cruel manipulations of the puppets and female performers who are persecuted, tortured. The indoctrination of the perpetrators is powerfully represented with percussive shouting and mechanical body movement. Viewers were astounded, immobilised, mesmerised.

Prinz Gholam (Wolfgang Prinz and Michel Gholam) performed at the Temple of Olympian Zeus. Beside beautiful Corinthian columns they brought memories of the statues of ancient Greece into the present. Dressed in unremarkable clothes, lying on the ground or standing, they shifted their bodies through a series of ‘frozen in motion’ poses adjacent to the temple’s grandeur, directly drawing our ordinary contemporary bodies into relationship with Greek antiquity’s idealised, conceptual inscription of the human form.

Again, in Kassel, I had so many favourite works. Algerian artist Narimane Mari’s film, Le Fort des Fous addresses the propagandist, unrealised promises of European colonization. It is shown in Ballhaus, an aristocratic residence in the hills outside Kassel, and follows the interactions of a wandering band of people who form a utopian society that gradually degenerates.

Indian film maker Amar Kanwar’s Such a Morning in the Neue Gallery, poetically explores an elderly man’s changing perceptions, his memories, realities, when he leaves his esteemed professional life and seeks the calm and intense introversion of solitude. Romanian artist Daniel Knorr’s smoking tower on the Fridericianum seemed a one liner at first, but in the context of Kassel and my research of the city’s Nazi history, it brought to mind the destruction of learning alluded to in the theme ‘Learning from Athens’, such as humanist principles, logic and order, represented by the Classical architectural style and status of the museum.

Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama’s draping of the gateway into Kassel with recycled, abject jute bags used to transport goods all over the world, resonant of labour, trade and capitalism, was spectacular and provocative. Titled Check Point Sekondi Loco, the jute bags cover the Torwache on one side of the broad avenue leading into the city centre, a heritage building now a court house for refugee appeals, and the Hessisches Landesmuseum (the local district’s history museum) on the other side.

American collaborators, Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens, took people on walks around Kassel’s parkland introducing the concept of ecosex—nature as lover—most amusing and thought provoking.

Some of the wonderful, stand out works for me in the Palais Bellevue were Lala Meredith-Vula’s photographs of sculptural haystacks in Sarajevo, relating them to the country’s history of war and repression; Roee Rosen’s hilarious video, The Dust Channel—vacuum cleaners as sex objects; Regina José Galindo’s La Sombra (The shadow) where she’s pursued by a military tank—obvious but riveting; Olaf Holzapfel’s beautiful compositions using straw titled Zaun (Fence) contextualised by traditional embroidery.

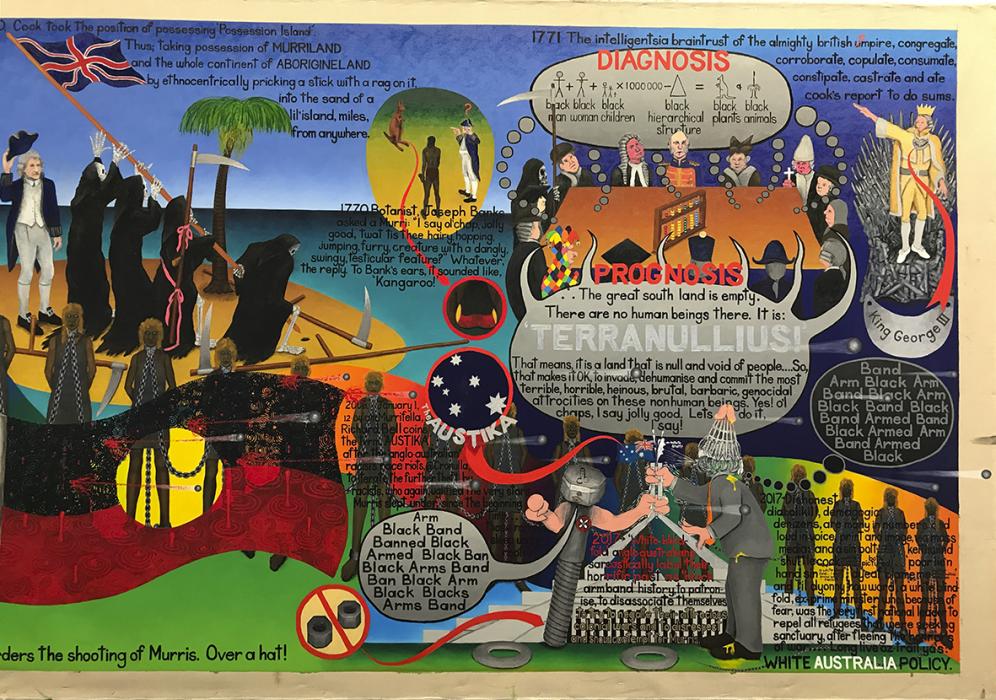

In the huge industrial complex, Neue Neue Gallery (it was Kassel’s main post office and mail sorting centre) I loved Gordon Hookey’s very witty retelling of the history of Queensland, MURRILAND! where, using text and image, the Indigenous people defeat the British invaders. Around the back of his large mural is an equally huge video installation by Theo Eshetu titled Atlas Fractured, where iconic, totemic images transform magically into contemporary people’s faces, drawing kinship with the mythical past into the present. Superb.

Sami artist Joar Nango’s collaborative performative installation, Documentation of European Everything is reminiscent of Fluxus Happenings. He and his friends drove from Athens to Kassel in an ancient bus that became part of the installation along with objects related to Sami cultural practices, such as animal pelts. In the evening performances of Sami music were held in the installation, and outside more metal objects were made using recycled material and a makeshift blacksmith’s forge.

Finally, Nigerian artist Olu Oguibe’s monumental obelisk in Königsplatz, Das Fremdlinge und Flüchtlinge Monument (Monument for strangers and refugees), on which is inscribed ‘I was a stranger and you took me in’ certainly will remind people of the history of wars, invasions and the ongoing movement of displaced peoples around the world, their (cruel) reception in the countries in which they seek refuge, and the ideal of humanitarian ethics. Good one for Australia.

How did your perspectives on the show chime with, or differ from, what you were hearing in the media? In particular, what did you think of Australian responses, whether via media or conversation?

The online media had varying responses to documenta 14, but mainly positive. In Australia I have heard ZIP, apart from John MacDonald in the Sydney Morning Herald, and I’m guessing he didn’t like it much: ‘politically constipated, incoherent offerings in Kassel’. He goes on: It’s staggering to contrast the commercial buzz of Art Basel with the arrogance and complacency that distinguished Documenta 14. The show felt like a throwback to the utopian fantasies of ’60s counter-culture at a time when such ideas have never seemed more inadequate.

So what’s your take on this response? And, why do you think that, apart from John MacDonald’s vitriol, Australian media didn’t pay much attention to documenta 14, not even celebrating the work of the Australian artists represented there?

For me the accumulative impact of documenta 14’s two iterations is mixed. First, the exhibitions were very engaging because the themes and approaches were so varied, experimental, reflective, and often provocative. Historical works in the mix introduced artists unknown to me whose culturally specific works were the avant garde of their time, adding dimensions to my knowledge of modernist and contemporary art, and contextualising the contemporary work. However, large exhibitions in diverse, often site specific venues, need practical instructions, clear maps and informative publications and labelling. As an exhibitor I found the documenta publications perversely opaque, their design missing all the fundamentals of clear communication.

There has been little attention in Australia given to documenta 14, which is surprising given its reputation as a most significant international art festival, but Rebecca Gallo’s review in Art Guide Australia is an informative overview, whereas Alice L. Hutchison is less generous in A+A Online, where the iteration in Athens is portrayed as condescending. John McDonald’s review in the SMH illustrates his disdain for all but conservative, ‘aesthetic’, contemporary art. In his view political art is inept, art and politics being antithetical—art doesn’t change anything. So, the art in documenta 14? Pathetic.

As an exhibitor, I feel documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel is a testament, expressed in experimental multimedia languages, to the insightful engagement of artists all over the world in the concerns of our times.

_0-itok=deLwj_af.jpg)