Dirty Happy Hippie: Kaftans, mud and colour in Venice

Somehow, I’ve managed to avoid the Venice Biennale, despite over twenty years of thinking and writing about art. Every year it comes around, I’ve been either too busy, too poor, or too dogmatically localist to burn carbon for art. I’ve railed against the disconnect between art tourism and sustainability, and the ongoing hegemony of north over south, of centre versus margins. But this year, the stars aligned and I finally made it to the city that sags with the weight of our collected dreams.

I never expected Venice, in some kind of Baudrillardian twist, to remind me of Las Vegas. Everything is suspiciously diminutive and compact, as with a movie set or some other zone of carefully constructed and controlled artifice. Every shred of artfully flaking paint on every charmingly dilapidated building has been rendered in megapixels by tourists from Beijing to Buenos Aires. So, what better place to stage the art world’s biggest carnival? You can dispense with the masks since everyone is already playing a role anyway.

But I’m being disingenuous, because the city of Venice reminds me I’m a tourist like everybody else – and the locals tell me with their expressions that they’ve had a gutsful of me and every other international interloper who can’t string an Italian sentence together, or who ignorantly squeezes a piece of fruit in a market stall. A word of advice for first time travelers to the sinking city… DON’T TOUCH THE FRUIT! The country that brought you the slow food movement doesn’t take kindly to the amateur caress of their artisanal produce.

If, however, you’re more concerned with art than the artisanal,(1) the Biennale has it by the truckload. I wonder if there’s a technical term for being overwhelmed and underwhelmed at the same time? How, seeing so much of something makes it all matter so much less? Not to mention, this particular constellation of art is the most reported, tweeted, and grammed visual practice in the world. So, how to say anything new, particularly at this late date, when all the problems of Christine Macel’s Viva Arte Viva have been remorselessly picked over? Too hippie-feel-good, not political enough (as if the former wasn’t it’s own political strategy). The show is organised into nine ‘Trans-pavilions’ such as the Pavilion of Joys and Fears, the Pavilion of Time and Infinity, and the Pavilion of the Common, with its emphasis on participatory work. The names alone of some Pavilions made me wobbly with anticipation, like the Pavilion of the Earth, but while everyone raved about the Charles Atlas video featuring sunsets and a drag monologue about the patriarchal abuse of nature, I ended up vibing with Nicolás García Uriburu’s 1970s documentation of dyeing the Venice canals bright green. Perhaps it was the site-specific resonance, or the flatness of the poster aesthetics, or maybe the way lurid green united the images like sentient slime crawling across the wall? Because I was also seeing documenta14 before (Athens) and after (Kassel) the Biennale, elements of that exhibition became provocatively entangled with my Venetian interlude, and in this case, the whole of Uriburu’s oeuvre, and others in The Pavilion of Earth meshed with Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens’ particular brand of ecosexual activism (always a good thing).

The Pavilion of the Shamans seemed promising, presided over by Ernesto Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar (2017), modeled after the sacred spaces of the Huni Kuin for practicing ayahuasca ceremonies. But, to my knowledge, in spite of representatives of Huni Kuin inaugurating the giant psychedelic string tent, there was no ayahuasca to be had, and the macramé big top simply ended up being an opportunity for viewers to drum badly on the handful of instruments scattered around. It’s likely that a deeper engagement with Amerindian ‘cannibal metaphysics’(2) could be had with the late Juan Downey’s video work of his life among the Yanomami, The Circle of Fires Vive (1979) at the entrance of the Pavilion of the Common.

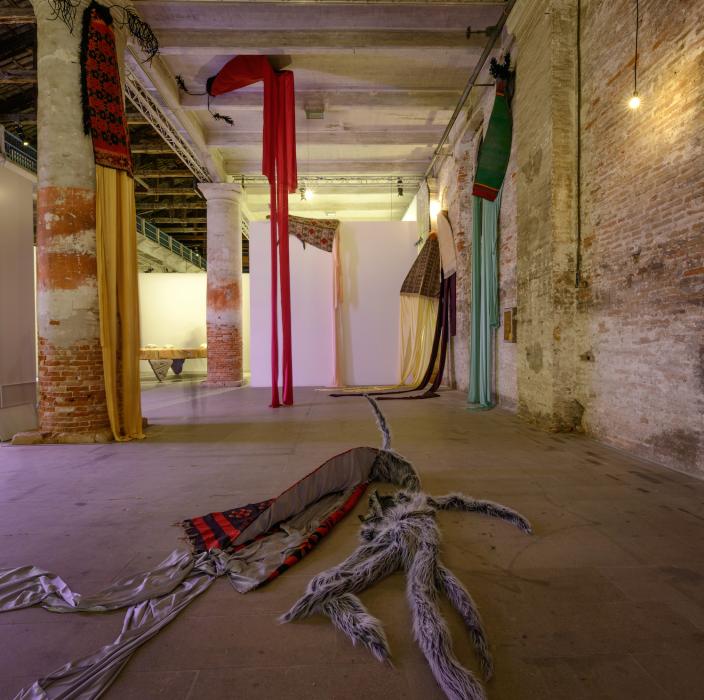

Sheila Hicks was clearly the queen of the Pavilion of Colours, with her giant multihued pompoms wedged against a wall, although, heartbreakingly, signage decreed that, like Venetian fruits, these vibrant orbs were not to be touched. In spite of my reticence to join Neto’s drum circle I would have happily launched myself into these. But my favourite work of all was Petrit Halilaj’s Do you realise there is a rainbow even if it’s night!? (2017) in the Pavilion of Earth. Halilaj made human-size moth costumes, complete with fury bodies and wings made from Kosovan rugs. These thick, colourful woolen geometries literally climbed the walls of the Arsenale, with a metamorphic residue of satiny trains trailing behind. There’s not a lot of animal in Viva Arte Viva, but there are a lot of textiles, so Halilaj’s wooly becomings-moth were all the more gratifying, while Francis Upritchard’s scraggly octopi cast in bronze with a weird, chalky white patina recalled what I had just seen in Athens: Mycenean vases and jewellery covered in those spectacular tentacular creatures.

Upritchard was part of the Pavilion of Traditions, next to Michele Ciacciofera’s found and crafted objects, including an array of books: one of honeycomb, another of handmade paper and caraway seeds spelling out some kind of prayer or invocation, and books made of bound textiles. Of course, these bibliographic objects could easily have been part of the Pavilion of Artists and Books, or of the very bookish documenta.

The Dionysian Pavilion, supposedly a celebration of the female body, featured documentation of Jelili Atiku’s performance Mama Say Make I Dey Go, She Dey My Back, at the Vernissage, during which dozens of women from around the world were recruited to wear satiny pink robes, carry a portable altar with mortar and pestle across Venice, and get ferried around on Gondolas, all the while presided over by the artist as high priest in a giant headdress, distributing amulets. While its meaning seemed somewhat nebulous, the Yoruba-inspired ceremonialism and ritualistic frocking up was infectiously joyful and suitably solemn. (You can see the whole event here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HksbgVJ5KuE).

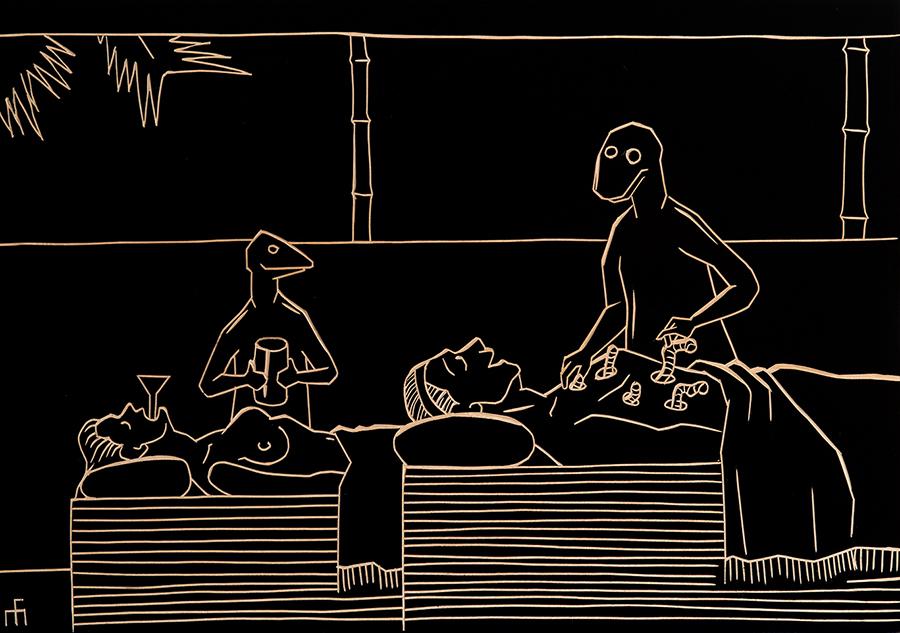

By contrast, many of the National Pavilions were unmemorable, although certain images stuck in my mind, or, in the case of Italy’s pestilent Imitazione di Cristo by Roberto Cuoghi (2017), mildew stuck in my nostrils: this work, made of mouldering Christ effigies, came with its very own spore warning. There was much-needed humour from the Finnish Pavilion’s muppet video conference send-up of cultural export and the intense pressure for artists to perform a nationalist agenda. Meanwhile, the Latvian pavilion simply went gonzo with Miķelis Fišers hilarious carved line drawings of aliens, avatars, and yes, more ayahuasca ceremonies.

While Great Britain’s Phyllida Barlow played games of incredible scale, her sculptural forms were ultimately, frustratingly static, while France’s hipster sound studio by Xavier Veilhan, was too cool for viewer participation. Anne Imhof’s Golden Lion winning German Pavilion, the performative installation Faust (2017), was out of action when I visited – something akin to Pirates of the Caribbean being closed for repairs when you visit Disneyland. (3)

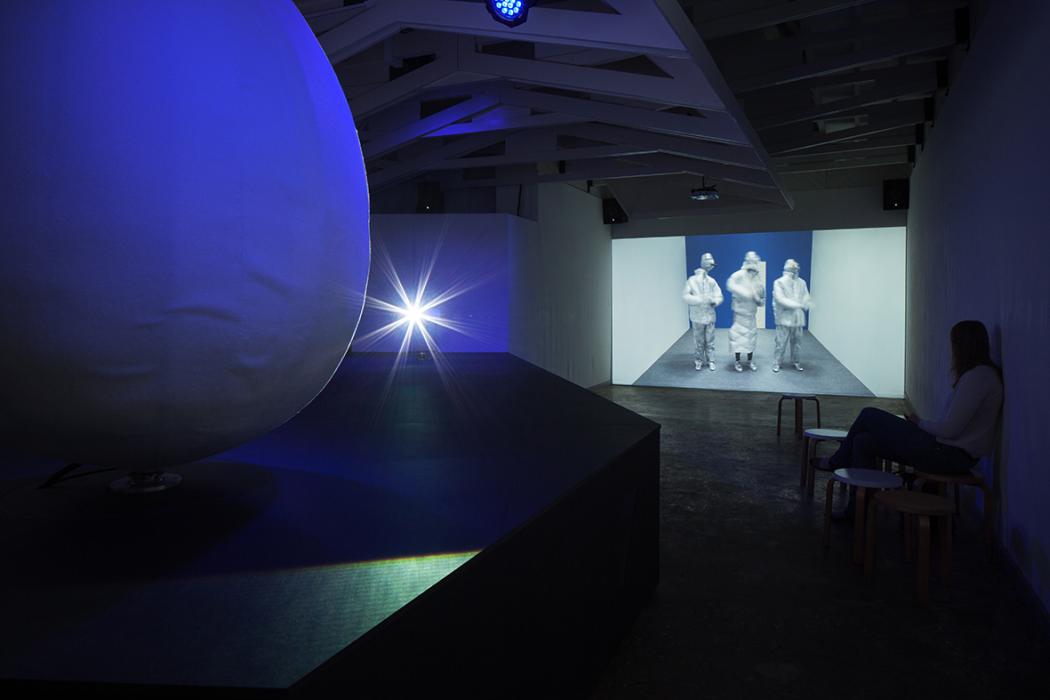

Closer to home, Tracey Moffat’s My Horizon at the Australian Pavilion, with its two photographic suites and two video works, seemed piecemeal and disconnected compared to New Zealand’s tour de force: Lisa Reihana’s Emissaries. After preliminary outings in Auckland, Melbourne and Brisbane, Reihana’s video epic had further additions to its already sweeping narrative arc. For those who haven’t seen the scrolling colonial-style animated wallpaper, in which each vignette is a live-action story, told by contemporary Pasifika performers who – tihei mauri ora! – breathe life into ancestral traditions, it’s difficult to convey the work’s scope and emotional range (made doubly effective and affective by James Pinker’s incredibly poignant soundtrack). In my completely unbiased opinion I’d rate this as the most significant, all-encompassing, de-colonial artwork to date. The only other work which commanded such rapt attention was Moataz Nasr’s multi-channel video The Mountain in the Egyptian Pavilion, a powerful narrative about fear of the unknown, although his audiences, like me, may simply have been avoiding a torrential downpour. Since the floor of the makeshift Egyptian cinema was rather charmingly covered with earth, the sudden rains made for a rather squelchy cinematic experience. What with mud, coloured kaftans and ayahuasca references peppered throughout the Giardini and Arsenale, I started to think that perhaps Viva Arte Viva should have named itself after that somewhat dubious concoction of coffee, chai and chocolate known as a ‘Dirty Happy Hippie’ served at establishments like Lentil as Anything. Of course, documenta 14 and collateral events in Venice such as the mind-bending The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied. at the Prada Foundation got more points for intellectual rigour. Viva Arte Viva never fully delivered on its feel-good proclivities beyond a kind of teasing series of quotations (that is, we never got dirty in the Pavilion of Earth, or lewdly liminal in the Pavilion of Dionysus, and no, we didn’t imbibe anything in Neto’s ayahuasca tent). And while I would have liked to have proclaimed myself mud-soaked and affect-drenched after the Woodstock (rather than Olympics) of art, I came home with my thirst for the extraordinary only partially slaked. Maybe I need a beetroot latte.(4)

(1) Miranda Dempster, a New Zealand designer and long-time resident of Manhattan, moved to Brooklyn and was so knee-deep in the boutique, she was compelled to create ART-IS-ANAL badges, to be worn at Farmers Markets or exhibition openings, you decide.

(2) See Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s Cannibal Metaphysics: for a post-structural anthropology. Trans. Peter Skafish, Minneapolis: Univocal, 2014.

(3) This happened to me on both of my visits to the exemplary establishment, and to Southern Californians is a misfortune akin to being struck by lightning twice.

(4) Yes this is really a thing. Turmeric lattes are so 2016.

_0-itok=deLwj_af.jpg)