The Avoca Project 2005 — 2016

Lyndal Jones is an artist who focuses on the politics of context, place and gender through very long-term projects. In 2005 she set up The Avoca Project, an international art project in regional Victoria, centred on Watford House, a pre-fabricated gold-rush residence imported as numbered planks from Scandinavia via Hamburg in 1852. Over its twelve-year life The Avoca Project has engaged with a wide range of art projects, including land works, exhibitions, performances, film showings, concerts and symposia. The following conversation was conducted via email during June and July, 2017. Lyndal was in Europe and Maria in Melbourne.

Maria Miranda: I first encountered The Avoca Project in 2007. At the time the idea of climate change or global warming was certainly a political and environmental concern, but not many artists were engaging with the importance and urgency of climate change. In 2006 Al Gore had just unleashed his film “An Inconvenient Truth”, a year after The Avoca Project began life, and it seemed to me then that the project was very much ahead of its time in both its unusual form – a house – and the issues and ideas that formed its core. It was also right on time – a poetic and visionary response to the times, especially given Gore’s terrifying data sets. Lyndal, I wanted to ask you first about the origin of The Avoca Project. How did it come about? How did you come to have a house at the centre of the project – what were you thinking/planning? Was global warming central to the project from the start? Or were there broader ecological and feminist ideas and visions that instigated it?

Lyndal Jones: Most artists I know have storerooms full of artworks that were expensive to make and that they don’t now know what to do with – that was never the case for me as I make performances that extend into video works. But similarly, because my works have a terrible tendency to become large-scale, I’ve often had the guilty thought that the amount being spent and the materials being used would buy someone a house! On another track, I have also always been somewhat uncomfortable with the mercantile aspect of the art scene that leads to artists establishing a recognisable ‘mark’, becoming a ‘brand’. My sense is that the one thing we, as artists, have going for us is our freedom to engage with the social conditions as we need to, to respond in the most appropriately imaginative way that we can. To do other, to meet a market that we can only imagine because it has already disappeared, is to actively resist our inter-relationship with all other elements of the world around us. So these two concerns, the need to become more sustainable as an artist, along with the need to test myself in a different way, led to this ‘functional-art’/ sculpture-like project.

But that was an undercurrent. It wasn’t the beginning. In 2004, when I started looking for some land, to make I knew not what really, I was told that this decrepit, uninhabited old house that I had known of, and loved, for years, was to be sold. At the same time, I was becoming concerned not only about global warming (‘climate change’ is such a softening euphemism) but also about my realisation that artists didn’t seem to be addressing it at all. I was half way through a long series of video works addressing the lack of demonstration of emotion in western cultures but, given the appearance of the house, my concern to find images beyond polar bears on icebergs to identify climate concerns, and my undercurrent issues with sustainability of materials in the arts, everything coalesced around this very fine old house in a little town in central Victoria.

It helped that the house was declared beyond repair as that meant I could buy it. (Well, actually it meant that my brother’s family lent me some money so that I could rent via the bank!) And, most particularly, it helped that its powerful presence as a grand, double storey edifice overlooking the Avoca River and its extraordinary history (brought by ship as numbered planks from Scandinavia via Hamburg during the Victorian gold rush of 1852,) meant that the project already had, as its central image, a first-generation immigrant. And it had literally arrived by boat.

As another undercurrent, when I started the project, my feminism was so deeply ingrained in my art practice as a fundamental driver of my image-making that I didn’t consciously set up a house as a feminist project. I was more focused, at the project level, on the ways in which many artists had worked with property in the past (Gordon Matta-Clark’s cut buildings, Rachel Whiteread’s use of a house as a removable mould for a sculptural version, Gregor Schneider’s digging out of his own home for his ‘House u r ’ project.) I remember writing at the time that I wanted the house to become an artwork by making it more liveable, rather than less so in specific reaction to these acts of destruction. It’s that sustainability issue again.

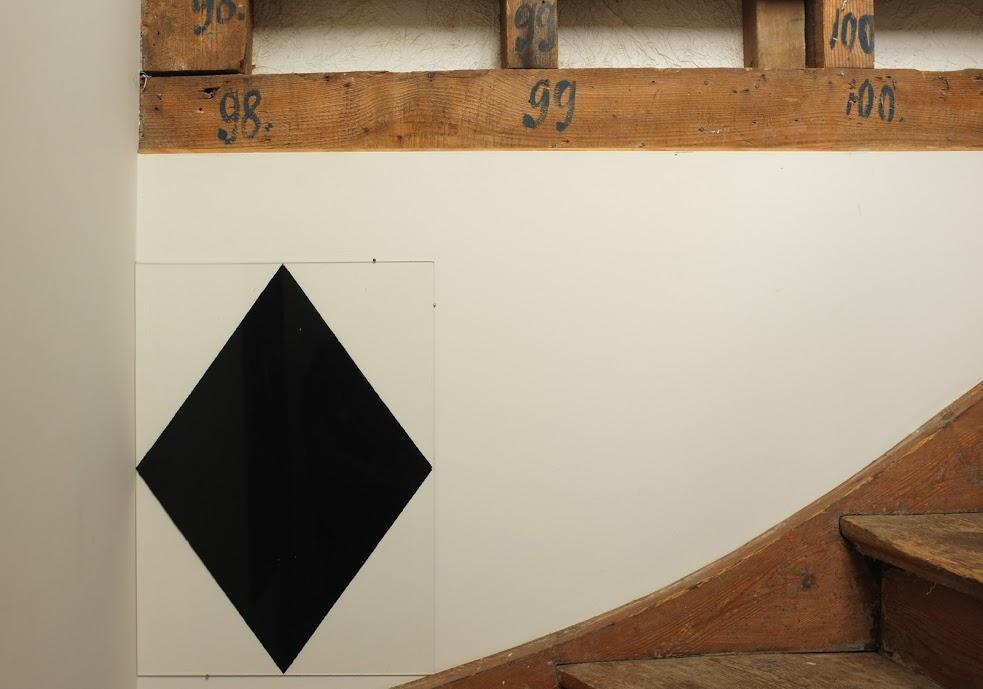

Interestingly, twelve years later, having been invited to create a ‘retrospective’ exhibition of the project for the Wyndham Gallery in Werribee at the end of this August, 2017, I find myself wriggling out of being ‘definitive’ yet again. I am more interested in creating another direct experience through the idea of a sustainable-sculpture project. So I will make a new ‘house’ out of all the bits of the house that are either still waiting to be incorporated or that have been removed.

Thus an over-elaborate portal added by the previous owner that I had removed and some iron lacework panels that once formed a balustrade and were in the shed, along with assorted pieces of timber from the original construction (I guess, as Ikea does, they gave them extras), a huge plaster ceiling rose and two plaster columns, still in their boxes will all, finally, have their moment.

But, beyond finding various opportunities such as this to create more sustainable art, I have found a much deeper relationship with the house and the environment. It arose by accident really as I found myself continually correcting artists’ exhibition invitations when they wrote that the event was to take place at Watford House. This detail made me increasingly uncomfortable until I realised I needed us all to say we were working with Watford House…that, until we realised in a deep way, and acknowledged it through our language and behaviour, that we are the world together in interaction, we would continue to exploit and thus destroy it.

This focus on materiality and relationship is not, of course my idea but one that is now well recognised. It is the world of Félix Guattari’s ‘three ecologies’ the ‘posthuman’ of Rosi Braidotti and the ‘more-than-human’ of Erin Manning. It is the heart of what constitutes the necessary changes to deal with climate change (ie to stop imposing our will on the world around us). However, as I watch artists who come to work with the house (including myself) and others who spend time there all struggling to match this concept in their everyday actions and language, I realise what a difficult proposition it is to enact.

MM: Last year, 2016, The Avoca Project celebrated its twelfth year, and unfurled the evocatively titled exhibition, a wallaby once sat here - small acts of celebration and concern… ecology and the feminine. This project brought together many of the themes, ideas and issues that have run throughout the The Avoca Project’s life – in particular the concern with ecology and the feminine. Being one of the many artists invited to participate in the project I was intrigued by the particular ideas that you brought to these concerns, in particular the notion of ‘waiting’ and ‘generosity.’ Could you explain how the ideas of waiting and generosity work for you, and how they are related to ecology, feminism, the feminine and art practice?

LJ: The business of waiting is at the basis of my learning about creative process. It’s tied to the idea of ‘working with’ rather than ‘working on’ or ‘working at’… that I have mentioned above. I believe ideas continually elaborate through a number of stages as the act of creating is itself one of becoming more differentiated, more aware of what is being offered, and then becoming more skilled materially in response – thus making increasingly rich offers in return. With such a responsivity cycle the more generous the offer, the richer and/or more rigorous the response.

It strikes me that the business of waiting is incredibly well known to those who some philosophers call ‘the other’ i.e. all those who aren’t white, middle-aged, middle-class men. There is something here about refusing a certain kind of patriarchal power ‘over’ others, ‘over’ the environment. The thing though is to not just be able to discuss this but to enact it. Change at this level is really hard, including for those who, while skilled at waiting, see it as a negative act. The act of waiting with an attitude of generosity even towards one’s own failure to engage differently within the world is also therefore really pertinent.

I found a great proverb that I think might apply here. It goes like this…

They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.

MM: I think your idea of ‘working with’ was something that I fully experienced with ‘a wallaby once sat here.’ Too often the experience of being invited to show work can be a thin and stressful experience of ‘installing’ with the greatest speed and then de-installing even more rapidly. Instead, you created a ground for meeting the other artists and engaging with their work that happened gradually over the course of several months through sharing and making meals together and staying at Watford House and in the town of Avoca with locals. It was a very surprising and nourishing experience. The idea of ‘withness’ seems to be central to your project and so important to your practice I wonder if you could elaborate on it?

Lyndal Jones: That’s interesting. I think this is addressing the idea of ‘withness’ from a different angle. My approach with developing group shows is to first recognise that this is an ‘out-of-town’ experience for the artists and for most of the audience. Furthermore, to recognise that, while there is usually a shortage of funding, there is both time and the possibility of creating a community that is usually enriching for the artists and, by creating large exhibitions with a research edge, there is a real reason for people to come a long way to experience the work. Sometimes this backfires. It’s very hard for some people to spend time in such a tough environment, especially with me refusing to ‘lead’ them and insisting on just ‘waiting’. But it works really well when there is a mixture of artists and an exhibition as a final outcome.

Beneath this attitude is one of deep respect for the differences in approach that different artists can bring to projects and, more generally, to each other. I have been really fortunate to have had some wonderful mentors who have taught me this. One was the extraordinary Swiss curator Harald Szeemann. I remember a group of artists from all over the world staying together in a hotel while working on the Kwangju Biennale. Every evening he would be actively interested in what each of us was doing, no matter how well known we might or might not be, and this despite most of us being engaged with other curators’ projects. I had never experienced such deep respect and support for the courage it takes to produce artworks under pressure. Another was Carolee Schneemann who on one occasion, without knowing me well, held an afternoon tea party to introduce me to a group of New York women artists (and their cats) and, on another, walked me through a big Fluxus show at the Whitney showing me where her work had been included only after her public anger at the rewriting of Fluxus history without many of the women who had been part of it. For a young, unknown, woman artist from Australia what powerful mentorship, what a deep learning in both respect for the whole community that constitutes a group that continually needs nourishment and encouragement if we are to continue. And in the constant necessity to speak out when invisibility strikes.

MM: One of the main events during the exhibition was the flower arranging performances that happened over the two weekends that the house was open and in most of the rooms of the house. Could you talk a bit about these intense and popular performances, performed mainly by local women over the course of the open weekends? How did these performances come about? How do you see the performances and their relationship to Watford House? Do they relate to participatory practices?

Lyndal Jones: I used to run a flower stall with various friends at the town market which takes place outside the house on Sundays every month. It was a way of connecting the project with the town. The flowers I sold or gave away were from my own or other people’s gardens but I also offered grasses and weeds I would collect from around the place. And an extended idea of the ‘flower-arrangement’ has always been a part of the decorative element of the house (perhaps as much to hide the amount of work needing to be done to repair the fabric of the interior). So I put an ad in the local paper to see how much interest there would be in a series of flower-arranging workshops and was swamped with enthusiasm. At first I thought I’d bring in someone to teach but there was no money so I did it – not as a way for those attending to become skilled at flower-arranging, but as a way to experiment with flowers as sculptural material. Everyone who had attended at least two workshops was then invited to take part in the performances.

The solo performances took place every hour, each time in a different room. Everyone who was there for the exhibition seemed as mesmerised by watching creative decision-making in progress as I was. What I was most pleased about was the dignity of this contribution to the exhibition. These performances, and their residue, became central to the event. Were they about ‘participatory practices’? I suppose so, although my concern was to work with these women (the oldest was 89, the youngest 14) to create performances that I thought could be transformational for both the performers and the audiences.

MM: On arriving at Watford House, during those two week-ends of the exhibition, one was struck by the sight of a large metal frame covered with netting – as if a bed – sitting alone outside the house, in the middle of the side yard. This was one of your contributions to the show. Could you tell me more about this work?

Lyndal Jones: Yes, there was a simple metal frame outside that I had had fabricated and then covered with netting. It included a futon mattress on the ground offering the possibility of a resting place…

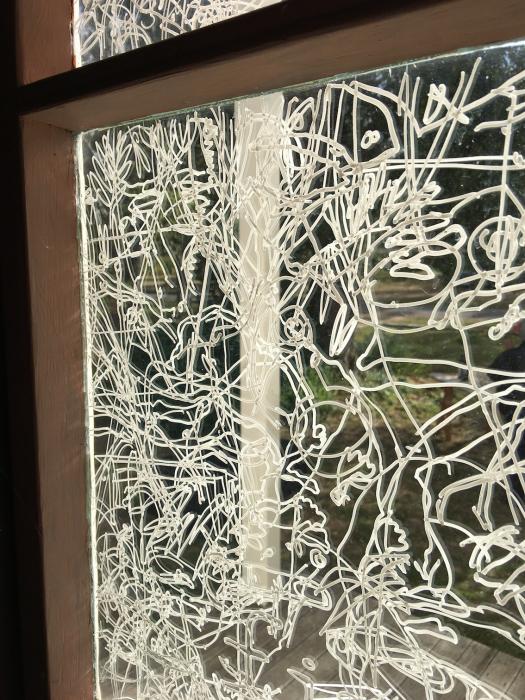

I was interested in the fact that, because there are no screens on the windows of the house, mosquito netting is needed inside. Also, because of the possums and birds predilection for eating all the fruit just as it ripens, many people were ‘netting’ their fruit trees. It’s an interesting relationship of refusal/survival I think. So the little netted pavilion in the yard (and moveable netted coverings in the vegetable garden and a whole netted room upstairs in another bedroom) was a way to ‘de-naturalise’ this aspect of our lives. Along with a huge fish-tank with goldfish that replaced the table in the dining room, these elements were my way of making the house already strange… a way of offering the possibility of the feminine and issues of the ecological to be already in conversation. And I stuck up a sign saying ‘A wallaby once sat here’ outside the kitchen window where I had actually seen one a few months before.