Zzzzz, Sleep and the Politics of Sleeplessness

Sleep is liquid and plastic, a permeable medium into which we sink or submerge.

—Valery Podoroga [1]

Zzzzz: Sleep, Somnambulism, Madness, curated by Mark Feary at Gertrude Contemporary, explored some of the gaps and movements between sleep and work, inertia and activity, dream and reality through key international and Australian works. Ideas of norms and fringes are used to emphasise alternative modes of communication through altered states. The exhibition presents a contemporary take on the body as an aesthetic object that is rooted in the representation of the sleeping figure in art history since antiquity—a body often depicted as a collapsed female body. However, the representation of sleep only provides a limited reading of the exhibition, as it further considers how the sleeping figure has become a site for broader socio-political concerns.

Sleep is political, as much as the body itself is political; as Jonathan Crary argued in his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the End of Sleep (2014), sleep is the last barrier to capitalism in a 24/7 economy. Insomnia affects one in three Australians and has become a governmental priority worldwide because of its effects on the economy and public health.[2] While Crary and others argue in favour of sleep as resistance, I think that sleeplessness can be good—as insomnia has ties to knowledge as ‘the sight of insight’, and as an ethical alarm bell—insomnia and other sleep ‘disorders’ need to be seen as resistance beyond established rhythms and dichotomies.[3]

Coming out of a club recently, I discovered how to capture my trouble with sleep. As I walked up Queen Street with the rising sun, I listened to music that I usually listen to when I want to fall asleep.[4] Through this slightly counterintuitive but simple experience, I realised that the sounds that bridge day and night have the power to take us from night to day with the same continuity—for awakening. This continuous cycle follows the natural flow of sunlight, and signals a major discrepancy with the generally accepted dichotomies of night and day, sleep and wakefulness, rest and work, activities of the underground and business operating hours… There is much to be gained from finding a more fluid equilibrium between those worlds for understanding the politics of sleep and sleeplessness.

Dreams and altered states

The gallery doors opened onto a series of drawings by Lee Hadwin, a UK based artist known for drawing in his sleep, ranging from automatic drawing to fantasy, romantic realism and graffiti, and could well be by different artists. On the left, The Telepathy Project assembled various everyday objects such as a pizza box, apples and straws, a chess board on tables of different heights as each assemblage was inspired by a dream and seem equally disconnected. These works destabilise the viewer on arrival by testing the common postmodernist reading of contemporary art based on the re-contextualisation of the everyday object that we tend to apply automatically. This new commission titled Objects seen in dreams should be manufactured and put on sale (after Breton) fails to pay homage to surrealism beyond our first impression of the work. While The Telepathy Project usually succeeds in using dreams as methodology for reinterpreting established narratives, the subconscious is used here purely for its creative-material power. It is also problematic, as Russian philosopher Valery Podoroga explains, to use dreams as cult-like ‘material’ for interpretation as if they are based on the assumptions and language of the waking world.[5] Dreams, he argues, are fully autonomous and warns against the instrumentalization of dreams.[6] In this work, each dream narrative is available on a handout, and perhaps the work fails here, because of its own conceptual methodology devoid of chance encounter; the work operates on the register of the funny rather than uncanny, it is comforting, rather than unsettling the norms and one’s self.

Politics of sleep

Inside Gertrude’s largest gallery, American artist Erica Spitzer Rasmussen’s work Dreaming of Sleep (2015) floated like the new spirit of capitalism, ghostly and mesmerising.[7] The dress confronts us with hundreds of the artist’s prescriptions for sleeping pills, rendered in miniature format on handmade paper. Rasmussen’s biopolitical reading of sleep addresses the widespread medicalisation of sleeplessness—and its aspect of control over our body and mind. While scientists don’t exactly know why we sleep, sleep has become commodified as biological capital. Philosopher Alexei Penzin points out that in Capital Karl Marx had already considered sleep in his ‘Working Day’ chapter, and this had further developed in communist strategies for controlling the full life of a worker through architectures and music for sleep.[8] Sleep and labour are connected like the two sides of the same coin.

In the deep, darkened gallery space around Rasmussen’s dress, multiple artworks operate as field of references, testifying to the many lenses required for understanding sleep and dreams: political (Rasmussen), scientific (Chicks on Speed), anthropological and ontological (Mabel Juli), psychological (Javier Telléz) and social (Kate Mitchell). In front of Warhol’s seminal video Sleep (1963), I questioned the nature of the artwork as a reference, as Sleep, for me, speaks not so much about sleep but the dematerialization of art in a post-war context. Here, I see Warhol’s contribution mainly in relation to body politics, because it is a fundamentally queer work featuring Warhol’s lover John Giorno. In the act of filming, Warhol makes himself present as the flip side of the couple, as the one to be awake and ticking.

Sleeplessness or the wake-up call

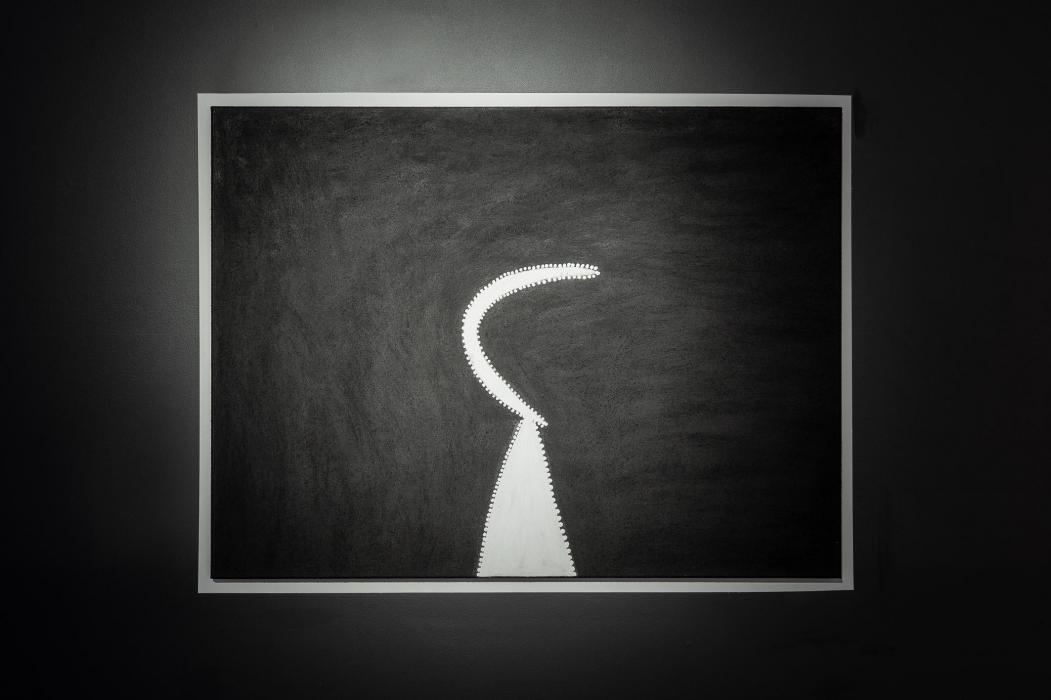

The image of Giorno asleep signals the ideas of non-productivity and autonomy in modern art, and resistance to ideas of productivity and performance.[9] However, the sleeplessness of Warhol points to overproduction and consumerism, just like in the work by Kate Mitchell or by Barbora Kleinhamplová and Tereza Stejskalová. Kleinhamplová’s Sleepers: A three-act play with six actors (2014) features actors seemingly asleep in the gallery who take turns in performing a wakeful state between dream and reality. The nearby Sleepers’ Manifesto (2014) by the same artists condenses the play into a video collage with photo-vignettes of workers napping in public. Together, the works callout our ‘chronically underslept civilisation’ and declare insomnia to be a ‘symptom’ of a social disease. Jonathan Crary identifies this disease as our changed relationship to labour because of a shift from an economy based on industrial production to a 24/7 attention economy that relies on surveillance. [10] It is also necessary to think further about the reasons why we wake at night, through a post-colonial reading of sleeplessness, as our current rhythms are also the expression of a colonial time imposed on our bodies. This is how I see Mabel Juli’s masterpiece Garnkiny Ngarranggarni (Moon Dreaming) (2016): the black and white painting representing a moon and a star alludes to colonial violence. The painting is a form of conformist and aesthetic reduction of an indigenous knowledge and a culture’s expansive relationship to the cyclical temporalities of solar and lunar movements in nature. To me, this painting is a sign for why we wake, for the unpleasant anxieties of our sleeplessness speaking to repressed histories. It is a wake-up call, the ‘practical anxiety’ that signals to the human mind that something is wrong and should be acted upon. This practical anxiety is our ethical mind speaking back at us and can help us to make good decisions. [11] Perhaps by listening to our anxieties—and not escaping by seeking distraction from them—could we tackle the ongoing issues produced by colonial and capitalist systems imposed on, and expressed by our bodies?

One of them

Of course, ‘I am one of them.’[12] Insomniac at times, and my reading of the exhibition is necessarily marked by my own condition. The exhibition seeks to blur our perception of reality in relation to what is commonly accepted, calling for a de-territorialisation of sleep and dreams. However, the dichotomy of day and night is reinforced by the two distinct spaces of the exhibition— the bright shop window gallery filled with light and the black box—set in opposition. And while a reference to ‘madness’ in the title is playful, and highlights the institutionalisation and regulation of sleep, dreams and parasomniac activities, it is problematic as it reinforces the same norms that the show seems to challenge. Notwithstanding that sleeplessness and sleep disorders are a symptom of contemporary society as much as they are an expression of it, as a kind of cultural activity.[13]

The complete but momentary blindness that affected me upon exiting the black box, reminded me of the blinding light at 7/11 after leaving the club. The intense light can be seen as the ‘white night’ of the 24/7 consumerist society, a culture in which we no longer work, but perform.[14,15] A constant pressure to perform comes from the denial of the value of latency, which Verwoert suggests can be dealt with by embracing our incapacities. He asks, how do we open up the space of echo and delay?[16] Rather than sleep, insomnia allows us to open up and embrace this space of latency, echo and delay in which time variably stretches. Even if sleep is the last natural barrier to the continuum of global capitalism, sleeplessness can be seen as unexpected, and freed time. [17] Why ask to get our sleep back when sleeplessness helps us to embrace the ‘gaps, open spaces and times’ that Crary identifies as disappearing in the 24/7 society? A fluid approach to sleep and anxiety is a way to challenge capitalist systems—or ambiguously perhaps—just another form of co-option. Insomnia can be a positive and generative time for emotional processing and thinking towards a more equal society.[18] It is an active form a dissent—and so is club culture.

[1] Valery Podoroga, ‘The Fork: an experimental cartography of sleep’ in Manifesta Journal No. 3, Spring / Winter 2004, p268, https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/jportal_jpvolume_00192108, last accessed 13/11/18.

[2] According to the Australian Sleep Health Foundation https://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au, last accessed 17/11/2018.

[3] Alexei Penzi developed an archeology of the philosophy of this in a lecture at the Fondazione Antonio Ratti in 2010 ( https://vimeo.com/channels/fondazioneratti/27021762, last accessed 08/03/2018); and also in reference to Levinas, In Praise of Insomnia (1976).

[4] Sleep music is a genre of its own, created to be listened to at night or it was commissioned specifically to fall asleep, from classical to contemporary composers.

[5] Valery Podoroga, ‘The Fork: an experimental cartography of sleep’ in Manifesta Journal No. 3, Spring / Winter 2004, p268, https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/receive/jportal_jpvolume_00192108, last accessed 13/11/18, p260-261.

[6] Ibid. For example, resolution often occurs in a dream itself rather than in the outside world.

[7] The New Spirit of Capitalism analyses new forms of capitalism and the role of critique in forming ideologies, how the move from Fordist hierarchical structures to interconnected workplaces based on initiative and autonomy comes at a psychological and material cost to society, rather than liberating the workforce (see Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, Verso: London, 2005).

[8] Alexei Penzin with Maria Chekhonadsikh, ‘The Only Place to Hide? The Art and Politics of Sleep in Cognitive Capitalism’ in Warren Neidich (ed) The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism: Part Two, Archive books: Berlin, 2014, p 223.

[9] Jan Verwoert, ‘Exhaustion and Exuberance: Ways to Defy the Pressure to Perform’ A pamphlet for the exhibition ART SHEFFIELD 08: Yes, No and Other Options, Dexter Sinister, 2008 https://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/268726/9ab37b785ede7f850d731128deac8bb9.pdf

[10] Jonathan Carey, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the End of Sleep, Verso: London, 2014.

[11] Charlie Kurth, The Anxious Mind: An Investigation into the Varieties and Virtues of Anxiety, The MIT Press: Cambridge, London, 2018, p4. Through the example of an abolitionist who expressed an ‘uneasy’ feeling in his mind, Charlie Kurth shows that anxieties are a trait of human nature to be embraced, as it led him to realise that the slave trade was a mistake and to take action.

[12] In reference to Sara Arrhenius in her curatorial essay for the exhibition Insomnia, in Sara Arrhenius, Sofia Curman, Camila Larsson, Insomnia: Sleeplessness as a Cultural Syndrome, Bonniers Konsthall, Art and Theory Publishing: Stockholm, 2016, p 5.

[13] Think ASMR, anxiety relief videos, body movements and activities done unconsciously.

[14] A white night comes from the popular expression in French faire nuit blanche, meaning to spend the night without sleep.

[15] Jan Verwoert, ‘Exhaustion and Exuberance: Ways to Defy the Pressure to Perform’, Dexter Sinister, 2008, p90. https://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/268726/9ab37b785ede7f850d731128deac8bb9.pdf, last accessed 23/07/2018.

[16] Ibid, p 94.

[17] Jonathan Carey, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the End of Sleep, Verso: London, 2014.

[18] As flexibility over stability has become an argument for psychological health. Dr Peter Koval, Public Lecture, 23 May 2018, the University of Melbourne.

,%20opera-performance,%20Biennale%20Arte%202019,%20Venice%20%C2%A9%20Andrej%20Vasilenkoheader_1-itok=YKJHGwex.jpg)