Women Artists in Southeast Asia: Strength and Unity in Diversity

‘How can we acknowledge the unique contributions of women artists to Southeast Asian contemporary art history, whilst at the same time not be beholden to or overdetermined by the categorization ‘woman artist’? [1] This is the crucial question being asked in Gajah Gallery’s latest and ambitious offering, Shaping Geographies: Art I Woman I Southeast Asia. Curated by Dr. Michelle Antoinette and Dr. Wulan Dirgantoro, the show responds to that inquiry through a display of 40 very diverse works by 11 female artists who identify as being a part of the region.

The terms ‘woman’, ‘art’ and ‘Southeast Asia’ are big words. Where women artists are concerned, there is (still) a gross gender imbalance in the Southeast Asian art world. Interest in women artists from the region surfaced only during the 1990s and while their representation may have been steadily growing since, the arena remains a male dominated one. Questions also arise as to whether there exists a definitive kind of aesthetics that can be ascribed to the works of women artists from the region.

As for the region itself, any student of Southeast Asian studies will bring up the first principle of the field which is the very artificiality of the idea of Southeast Asia. The region is immensely diverse. Yet, it also shares commonalities brought on by cross-border interactions. The multiplicity of this region is just too complex for framing. This is why many past art exhibitions are mere documentation of underrepresented female artists. [2] The few that have gone beyond documenting rely on Western-centric theoretical models that disregard the different experiences of women in the region that would have informed and influenced their artmaking. [3] These complexities were probably what compelled Gajah Gallery to bring onboard two established researchers in the field of modern and contemporary Southeast Asian Art to take on the mammoth task of curating the show.

In a bid to move beyond the limitations faced by similar exhibitions in the past, Shaping Geographies chooses to emphasize the diversity of the region by framing space as constantly shifting and in flux. [4] In the show, the artists’ nationalities are not included on the wall labels. With this omission, both artists and their works are no longer bound to any one fixed place or confined by borders. The works are free to take on any form and meaning according to each maker’s unique and individual connections and experiences. True to its promise, the diversity in the show is apparent from the start. The forms and mediums on display are wide ranging, from two-dimensional works to installations and new media. But even more astounding is the unique context that frames and informs each piece.

This brings us to the first work in Shaping Geographies. Promise (2019) by Singapore-born-Sydney-based Suzann Victor is a work that crosses regional borders. The large and visually arresting installation features the use of red human hair to form rings of text on the floor spelling out words that relate to the female anatomy like clitoris, vagina and labia. A pair of white garments hang at opposite ends of the installation and drape over a long table laid with woks and four disemboweled bread loaves lit from within. Dealing with the use of the bodies of Asian women for sexual slavery by the Japanese army during World War II, the red and white that appears in the work is symbolic of the Japanese flag. First exhibited in 1995 in Tokyo, Shaping Geographies marks the iconic work’s first restaging since. The disembodied female form referenced in Promise was originally a means for the artist to circumvent a proscription imposed by the Singapore government on performance art in 1994.

Artist Savanhdary Vongpoothorn added a transcultural element to the transnational exchange seen in Victor’s work. Born in Laos, the artist who identifies as Buddhist, moved to Australia in 1979 as an eight-year-old. Her work reflects these multiple layers of influence in her life and artmaking. Created with the aid of traditional Japanese materials like sumi ink and hand-made washi paper, Footsteps to the Nigatsu-Do (2017-2019) is an ink rubbing of the complex and symbolic patterns found on the stone steps leading to the Nigatsu-Do temple in Nara, Japan. The work also marks her collaboration with Japanese Tanka poet and calligrapher, Noriko Tanaka. Embellished with the latter’s calligraphy and the artist’s fragments of sutra, the repetitive wave-like patterns and curvilinear markings on the nearly two-meter long washi paper (hung horizontally on the gallery’s walls) renders a meditative quality to the experience of walking and viewing the work’s entire length.

The act of collaboration, on a much bigger scale, is reflected in Geraldine Javier’s Catch of the Day (2019) which addresses environmental concerns around polluted oceans. For this huge installation, the artist worked together with her community to collect the blue seals of plastic drink bottles from trash, before cleaning, cutting and placing them into a long box. The view of the long plastic-filled blue ‘ocean’ forces you to pause and contemplate the enormity of the calamity that befall our oceans.

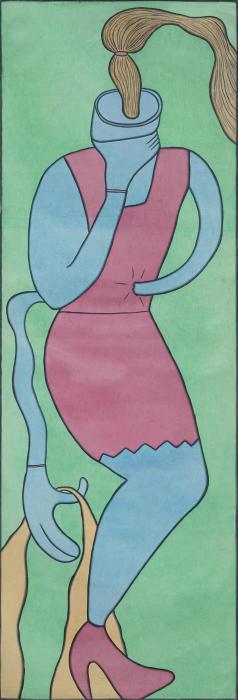

While Victor’s abused female bodies are merely alluded to in Promise, the late I Gak Murniasih’s embodiment of the female form takes on an abstract and graphic representation in a style derived from traditional Balinese Pengosekan painting, which she was trained in. Known for her explicit works that revolve around the themes of sexuality and violence, her three paintings in the show are tame in comparison. Disaat Itu Aku Sangat Sakit (At that Time I was very Sick, 2000) portrays a headless and distorted female form in bright, flat colours and dark, bold outlines. The hand reaching through the misshapen body is suggestive of pain while her choice of unnatural colours and unusual composition speaks of the rawness of her aesthetic expression.

Focusing on architectural forms and objects, Kayleigh Goh’s cement paintings on wood prove that women’s art is not and should not be a defined style and is most definitely no longer restricted to the body-oriented art that dominated earlier works of female artists. In her current practice, Kayleigh uses cement in place of paint, and together with found objects picked up from actual locations referenced in the title, she constructs artificial urban environments. Devoid of human figures, her work depicts blank walls and empty corners, and sometimes windows and doorways that look out into further emptiness. Jalan Tebrau (2019), depicts an artificial space in shades of grey with some play of light and shadows. The work feels ‘cold’ and evokes a jarring sense of loneliness and solitude. Yet, there is also a peaceful and calm feel to it not unlike the meditative tranquility that permeates Vongpoothorn’s ink rubbing. The work forces you to reconsider your notion of and relationship to space.

Shaping Geographies is certainly not short on star power. In fact, the number of established artists in the show far outweigh the five young emerging artists, four of whom form a collective. Of the former, the majority—seven to be precise—were born in the 1970s. This disparity is one let-down of the show. That these established artists are still actively practicing is proof that contemporary art making has no correlation to one’s age. But the glaring emphasis placed on them is at odds with the broad representation the show’s title hints at, suggesting the contemporary landscape of women’s art in the region is shaped mostly by practitioners from a certain generation.

Despite some inconsistencies, Shaping Geographies emerges largely triumphant. The show highlights the region’s vast diversity as well as some cross-border exchanges that shape individual experiences. It presents female perspectives of realities defined by their respective contexts, while still making room for commonalities to show through. However, with Kayleigh Goh and Muslimah Collective the only emerging artists in the show, there is a glaring imbalance in representation of artists across generations. Also, as four of the 11 artists in the show are represented by the gallery, it would be interesting to see if and how the list of artists and artworks exhibited might have changed had this been a show beyond the parameters of a commercial gallery.

[1] Gajah Gallery, “Shaping Geographies: Art | Woman | Southeast Asia,” Accessed December 9, 2019. http://www.gajahgallery.com/exhibitions.php?exhibition=203.

[2] Yvonne Low, "Women and Projects on Southeast Asian Women Artists (1990-2015), Re-modelling Art Worlds: Exhibitions," The Journal of the Asian Art Society of Australia 24, no. 4 (December 2015): 5-6.

[3] Yvonne Low, "Women and Projects on Southeast Asian Women Artists (1990-2015), Re-modelling Art Worlds: Exhibitions," The Journal of the Asian Art Society of Australia 24, no. 4 (December 2015): 5-6.

[4] Gajah Gallery, “Shaping Geographies: Art | Woman | Southeast Asia,” Accessed December 9, 2019. http://www.gajahgallery.com/exhibitions.php?exhibition=203.

-itok=cNbuvSbD.jpg)

-itok=1FTk6qpF.jpg)

-itok=PwmKv63E.jpg)