Timeless

In 1972, John Szarkowski, Director of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art said of Diane Arbus: ‘The influence that she’s had has been simply enormous because, when all of us, when we looked at Diane’s pictures it was almost as though we were starting again, as though we were back in the days of the daguerreotype, we were back in the days of Matthew Brady, and it was a new fresh, unused medium again.’ [1]

Arbus’ work, made over the course of only ten years before the artist committed suicide in 1971 at the age of 48, has gone on to influence some of the most important photographic artists that followed, including Nan Goldin, Robert Mapplethorpe, Rineke Dijkstra, Carol Jerrems, Wolfgang Tillmans and Cindy Sherman.

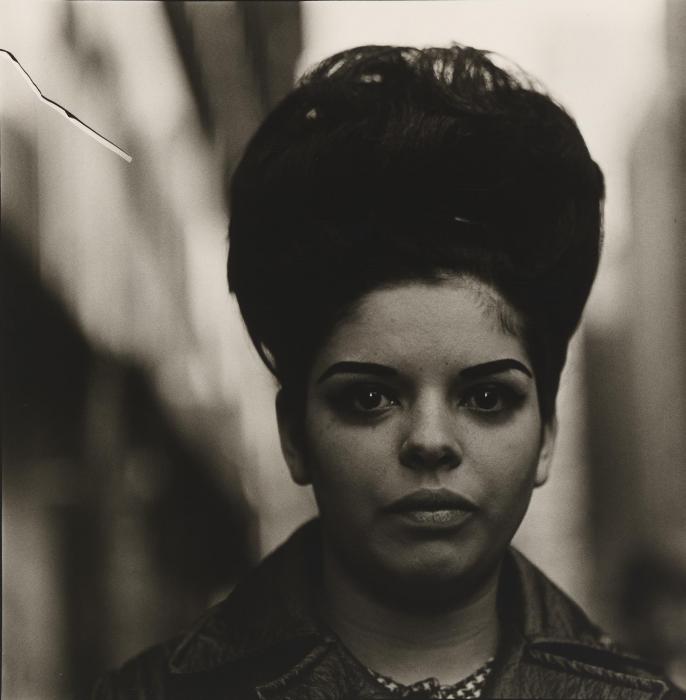

Diane Arbus: American Portraits at the Heide Museum of Modern Art, curated by Anne O’Hehir, provides a rare chance to see some of the most iconic and controversial works in the history of photography. The works on view include: A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C. 1966 (1966) with his long finger nails, cigarette and detached stare; Mexican Dwarf in his Hotel Room, N.Y.C 1970 (1970) nude except for a towel wearing a satisfied grin; Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey, 1967 (1967) who inspired the iconic twins in the 1980 horror flick The Shining; and A Jewish Giant at Home with his Parents in the Bronx, N.Y. 1970 (1970), in which a lumbering son towers over his parents who express a vulnerable mix of confusion and fear.

The exhibition brilliantly includes works by Arbus’ own influences—Lisette Model, Walker Evans and Weegee—offering viewers the chance to find connections and overlaps, highlighting the visual strategies that were completely of Arbus’ invention. Small side rooms are dedicated to her contemporaries Lee Friedlander, William Eggleston, Mary Ellen Mark, William Klein and Milton Rogovin. These rooms provide a critical context for understanding how Arbus made photography ‘new’ again. This near flow chart of photography’s development, from one generation to the next, helps to frame the artistic individualism that was emerging during Arbus’ time following a long history of photography rooted in the documentary approach.

Arbus was able to capture her subjects in a Bressonian decisive moment of their own identities. Confident yet self-aware, the subjects’ unique qualities are at once genuine and glaring. Arbus makes visible the everyday performance of the self and the tension between the desire to be seen for who we are and the societal pressures to conform. With the dramatic use of darkness and contrast, as well as black borders around each image, there is an undeniable theatricality at play. Each image is a stage with curtains drawn. Impossibly compelling, immediate and intimate, each photograph feels like a bit of truth never before told.

Raised sheltered within the New York elite, and later working as a fashion photographer with her husband, Arbus began making photographs for herself as a form of adventure. She admitted that the act of photographing was necessarily ‘cruel’ and to feeling ‘shame and awe’ around her subjects. She was interested in capturing the ‘gap between intention and effect’, which manifested in some cases as finding ugliness where the subject hoped to be beautiful. (2) This frankness about her privilege, as well as the frankness of her images, was entirely new and opened her up to criticisms of voyeurism and exploitation. One critique of particular weight was levelled by Susan Sontag in her article ‘Freak Show’ published in the New York Review of Books in 1973 and later in her seminal book On Photography:

The ambiguity of Arbus’s work is that she seems to have enrolled in one of art photography’s most visible enterprises—concentrating on victims, the unfortunate, the dispossessed—but without the compassionate purpose that such a project is expected to serve. Arbus’s work shows people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as horrible, repulsive, but it does not arouse any compassionate feelings. Nevertheless, despite this evident coolness of tone, the photographs have been scoring moral points all along with critics. For what might be judged as their dissociated and naïve point of view, the photographs have been praised for their candor and for an unsentimental empathy with their subjects. What is actually their aggressiveness toward the public has been turned into a moral accomplishment: that the photographs don’t allow the viewer any distance from the subject. [2]

In hindsight though, Sontag’s revulsion seems more about her as a viewer than it was about Arbus as a photographer. As author Maggie Nelson recently put it, ‘For the most part, it seems as though what is transpiring in these photographs is a real sense of play, joy, and engagement with Arbus—a readiness to pose and the pleasure of the time. It makes me think: who are we to judge whether or not these people are able to engage with her?’ [3]

In recent years the concept of the female gaze has made its debut, a delayed corresponding term to that of the male gaze coined by feminist film critic Laura Mulvey in 1975 to identify the objectification of women in film. Jill Soloway, writer, director, and creator of TV series Transparent, has been a forerunner in popularising the new term. Soloway gave a keynote address at the 2017 Toronto International Film Festival where they defined the female gaze as:

1. A way of feeling seeing. A subjective camera, one that attempts to get inside the protagonist, particularly when the protagonist is not a cis male. It uses the frame to share and evoke a feeling of being in feeling rather than looking at the character.

2. Using the camera to take on the nuanced and occasionally impossible task to show us how it feels to be the object of the gaze… It says this is how it feels to be seen.

3. Returning the gaze. Daring to say I feel you seeing me… I see you seeing me. It’s about how it feels to stand here being seen our entire lives. [4]

Arbus was perhaps the first artist to achieve the female gaze in photography. Though Arbus herself may have been naive and her motivations may at times have been problematic, she was able to make visible these layers of seeing and being seen, the power embedded in the act of looking or demanding to be looked at. Her subjects maintain eye contact with their viewers and communicate that they are not objects for our consumption. They are unabashed, they do not apologise for who they are, their ‘otherness’. They challenge us to reflect on our own assumptions about them and remind us that they must wade through these assumptions every day as they walk through the world.

So too with Arbus’ own experience, she said she enjoyed everything about her encounters with her subjects, including travelling across town to meet them. For a woman born in the 1920s, she had found a form of agency in her work that was completely her own. Inadvertently she was breaking down barriers for what a woman should or should not see, should or should not experience. After her death, it was revealed that in fact, Arbus had sexual relationships with many of her subjects. In light of her relationships, images once considered voyeuristic seem to expand into works about longing, the desire to know these people, to be close to them, to understand them, to tell their stories and, perhaps, to be free enough to become them.

Even in her absence, Arbus continues to connect new viewers to her subjects. Fifty years later, in the age of the selfie, these images can be understood as an earlier point along a timeline of our ever more isolated contemporary societies, in which interactions with strangers are too rare, and real connections are increasingly impossible. Ironically, even fifty years ago Arbus was using technology as a mediating device for human loneliness.

Seen through the psychopolitical fog of America’s current decline, Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park (1962), Boy with a Straw Hat Waiting to March in Pro-War Parade, N.Y.C. 1967 (1967) and A Family on their Lawn one Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. (1968) can be viewed as timeless portraits of the violence and banality embedded in American culture. Her ‘gap between intention and effect’ epitomises the perception of America on the global arena today—one attempting to convey power and influence, but instead appearing ignorant and corrupt. These works say, ‘this is how it feels to be seen’ in all our ugliness.

The world in which Arbus’ works were made is long gone, and today’s world is defined by a cacophony of images, unprecedented in human history. Whether read just as intimate portraits or more deeply for social and political layers, the enduring relevance of Arbus’ photographs is rooted in their accessible exploration of the act of seeing and how that relates to intimacy and distance, identity and belonging. In that way, these moments of time, captured serendipitously by a woman long ago and held fast in silver gelatin, are truly timeless.

[1] ‘Masters of Photography—Diane Arbus’ (video), 1972, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q_0sQI90kYI; accessed 16 April 2018.

[2] Susan Sontag, ‘Freak Show’, The New York Review of Books, 15 November 1973, www.nybooks.com/articles/1973/11/15/freak-show/; accessed 16 April 2018.

[3] Maggie Nelson in Real Worlds: Brassaï, Arbus, Goldin, exhibition catalogue, The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2018.

[4] ‘Jill Soloway on The Female Gaze | MASTER CLASS | TIFF 2016’ (video), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnBvppooD9I; accessed 16 April 2018.