To think about fraught things

We have to accept the unknown and, more importantly, the fact that we cannot understand and comprehend everything immediately. It is actually very Western to believe that knowledge is instant and can be consumed right away… It almost seems like we have to cultivate a practice of just being with art for a while before jumping into nervous and at times neurotic discussions about it. Language does not have to be available promptly. I think we should treat art as a space and experience that allows us the privilege to contemplate and endure the process of making new answers. [1]

There is value in embracing those rare occasions of unsolicited emotion that artworks can engender. There can be a tendency, within academic contexts, to disregard the emotional response. Such viscerally human reactions are considered too messy, too subjective, too blinding. Emotion is positioned as an obstacle to cognition. But when it comes to art, feeling can be a surprisingly valuable place to start. If an artwork makes you feel something, pursue that feeling: examine it, turn it over and over until it loses its hard edges, until you can trace a pathway between your thoughts and your feelings.

Over a two and a half month period last year, I visited The earth looks upon us / Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata innumerable times. Practically next door to my office, the gallery’s proximity allowed for frequent visits. Since its de-installation in September, I have often found my thoughts turning back to those works, and the quietly insistent conversation that I sensed unfolding between them. For this was an exhibition that immediately made me feel, and the process of charting a pathway from those feelings back to the criticality of thought is an ongoing one.

The earth looks upon us / Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata, brought together the work of four contemporary Māori women artists: Ngahuia Harrison (Ngātiwai, Ngāpuhi), Ana Iti (Te Rawara), Nova Paul (Te Uriroroi/Te Parawhau, Ngāpuhi) and Raukura Turei (Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki and Ngā Rauru Kītahi). Utilising film, sculpture, installation, photography, painting and the written word, each artist individually contributed works which, when brought together in the interlocking spaces of The Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi, generated a strange sort of alchemy.

The exhibition’s Māori title, Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata, was contributed by Rawinia Higgins, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Māori) at Victoria University. She explains:

The title comes from the whakataukī (proverb) highlighting how Papatūānuku is the primal parent to humans and that we all trace our genealogy back to them. Therefore our connection to the land is more than just a place to live, but a deeper spiritual connection tied up with our identity. [2]

This connection, between people and land – tangata whenua and whenua – holds a different quality than that suggested by the exhibition’s English title: ‘The earth looks upon us’. While suggestive of an earth that is animated through the act of looking, the intrinsic connection between earth and people is absent. The English language, shaped by a particular Western world-view, lacks the vocabulary to effectively re-characterise the nature of such a relationship. Perhaps this is unsurprising. Certainly it is reflective of a Western tendency to actively other the land—to see it as separate – in order to stake a claim of ownership. Again and again in the exhibition, such acts of othering were subtly refuted. The space of the gallery was overlaid with the tangible remnants of other places, it was traced with the persistent presence of whenua. Encompassing more than the physical tangibility of land or earth, whenua carries with it a sense of human connectivity, it implies a genealogy stretching from tangata whenua to Papatūānuku (colloquially translated as ‘Earth Mother’).

Ana Iti’s large scale sculptural installation Only fools are lonely (2018) brought the earth directly into the lower Chartwell gallery. A ten metre long cedar ramp rose gradually through the narrow space, acting as a support for over 200 hand cut and fired clay tiles. Clay, literally of the earth – of Papatūānuku – is laid over the built floor, hovering always just out of contact with the building itself. Around the corner, Iti adorned the building’s wall with a text work, posing questions regarding geographical place, absence and memory.

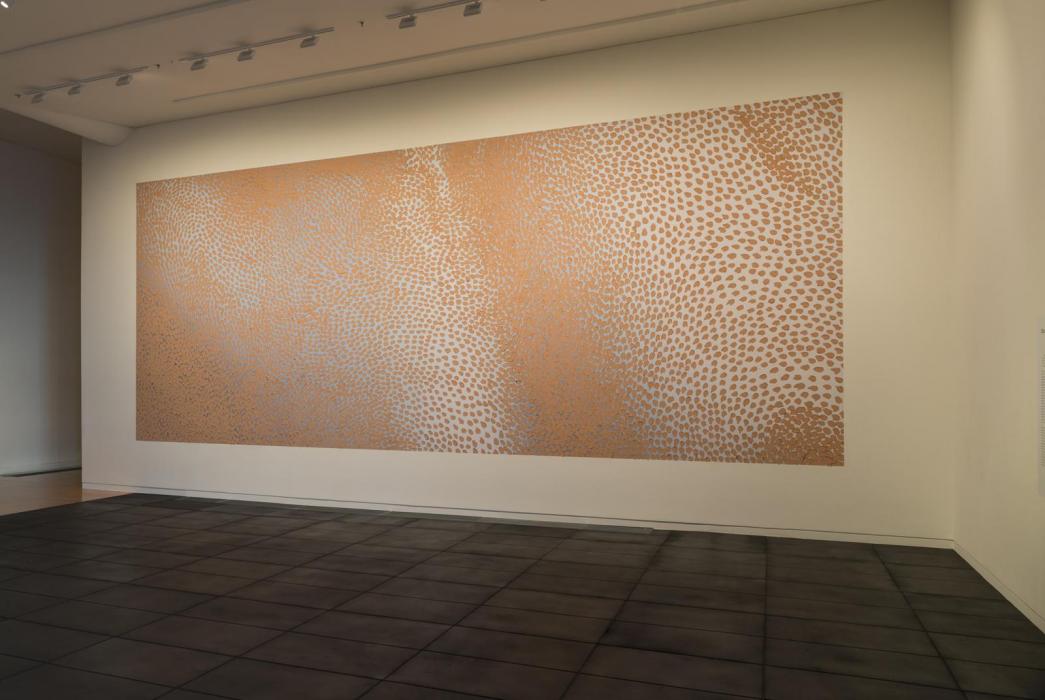

Earth became medium too, for Raukura Turei, in her large scale work Te poho-o-Hine-Ruhi (2018) created in situ prior to the exhibition’s opening. Produced through the gestural application of watered-down clay and pigment by hand onto the gallery wall, Te poho-o-Hine-Ruhi ostensibly depicts an abstracted close-up of a portion of the artist’s chest. The contours of Turei’s own body are transformed into a sequence of rhythmically pulsing lines which coalesce to form an intimate topography. The work’s title – which translates as the chest of Hine-Ruhi – refers to ‘the deity associated with dawn, who is said to be seen in the sparkle of light in the morning dew.’ [3] The textural richness of the work’s materiality allowed the changing light in the gallery to catch its surfaces, enlivening the clay’s rich ochres and pinks, Papatūānuku and Hine-Ruhi themselves appearing to illuminate the gallery space.

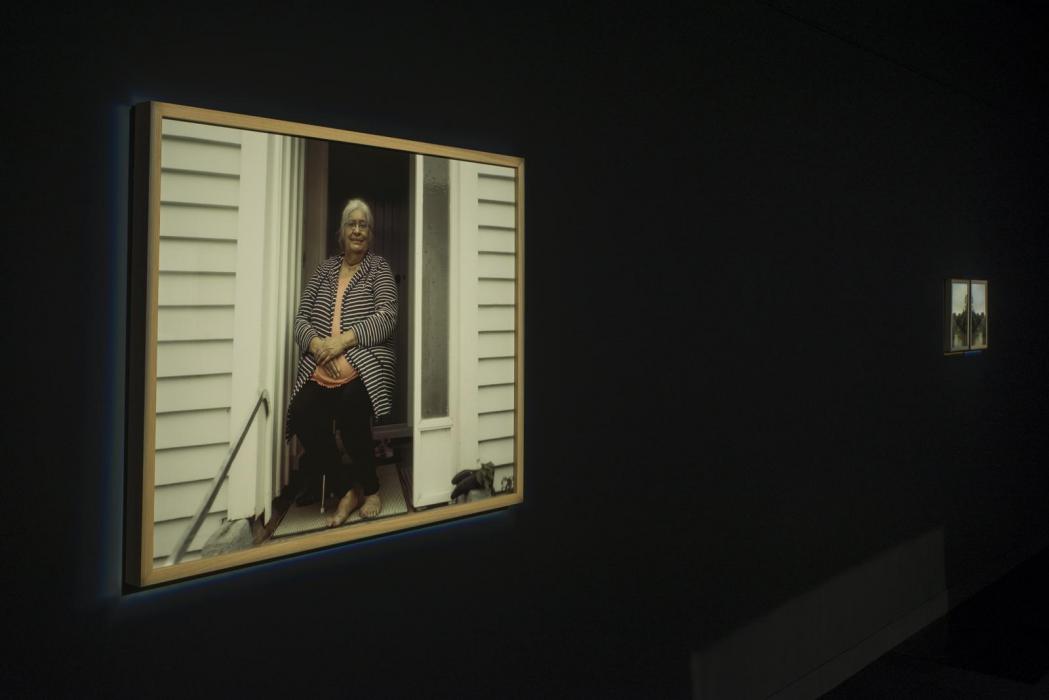

While Iti and Turei brought the earth directly into the gallery, Ngahuia Harrison’s and Nova Paul’s works overlaid the space with lens-based depictions of place. Harrison’s large-format photographs depict people and places loaded with personal significance. Her suite of work, Ngā Paepae Tapu (2018) transformed the windowless cube of the Kirk Gallery into a tangible network of connection. Picturing her aunts and the land to which she is connected, Harrison maps out a visual call and response between paired images which mesh together within the darkened space. Functioning as more than portraits or landscapes, her images contain a lyrical and emotive depth that reveals itself to the viewer incrementally. Frequently picturing family members and the ancestral lands of her iwi, Harrison has referred to her photographs an ‘apparatus of hope’. [4] Such terminology divests the camera of its mythical technological objectivity, situating it instead as a tool for emotional and political engagement.

Nova Paul’s 2010 16 millimetre film, This is Not Dying, created using three-colour separation, gestures towards the actions and quiet interactions which, when repeated through time, become the warp and weft with which we weave the texture of our lives. Layered together to create a polychromatic mesh of everyday life, the three colour-graded films create a depth of field unmoored from the constraints of illusionistic representation. The filmic surface shimmers as trees, figures and buildings vibrate through registers of colour: all at once they are apricot, turquoise and crimson. Paul leads us on a journey of return, back to the patterns of life in her family marae, Maungarongo.

There is a quiet and particular pleasure to be found in the repetitive act of returning. With each return to an exhibition, each journey through the space, we forge a deeper sense of recognition. What happens, though, when the return is no longer physical? When memory, with all of its slippages and imperfections, becomes the site for return?

Today, it is not difficult to revisit a work that is no longer physically accessible. Reproduction and dissemination of imagery is commonplace, the internet facilitating an expansion of gallery spaces. In the show’s aftermath I tried to find This is Not Dying online, and shouldn’t have been surprised to find that this was an impossible task. For Paul’s film is more than just a moving image, it is tangibly, materially 16mm film. In the gallery space the clatter and hum of the projector is as much a part of the soundtrack as Ben Tawhiti’s evocative instrumentation, the physicality of the medium unequivocal. Exposed to atmospheric imperfections the films gradually became altered, the physical site of the gallery becoming enmeshed with the land and people depicted. Rather than degradation, I looked at these gradual alterations as signs of life, of film as a medium which is, in the hands of an artist such as Paul, not dying. The inability to easily watch a digitised version of this film renders it at once less accessible, yet strangely more coherent and tangible.

Recollections of no-longer-visible works become enmeshed with the sites, histories and ideas that they invoke. In her text work, Iti poses the question, ‘does the brick recall Pukeahu’? In the wall text accompanying the work, Iti says of this work: ‘It speaks to the specific history of Pukeahu, a mountain flattened to make building materials for the city’ [5] In the exhibition’s wake, I learned that many such building materials were made by men from Parihaka during their imprisonment in Mt Cook Barracks in 1879. Men who had been arrested for peacefully protesting the government’s confiscation of their land had been forced to make, by hand, bricks forged from the earth of Pukeahu to be used by the government which had both dispossessed and imprisoned them. That Pukeahu is now the site of a National War Memorial Park, strikes a dissonant chord in the light of such a history.

After the exhibition’s closure, Harrison recalled the experience of standing within the textured space that she had created in the Kirk Gallery:

I remember standing in the dark, looking at the Aunties, you could hear the Ngāpuhi anthem from Nova’s work and the low bunker hum, it felt restful to me. I try to create that sort of contemplative space for people, maybe you’d even lie down if you wanted to. Because when I’m up home in my wharenui that sort of restfulness is what I feel and it’s a really productive space to be able to think, even about fraught things. I think the show as a whole felt like that for me as well. [6]

Her recollection reminded me of Ncobo’s words, urging us to allow art the time and space required to enable us to ‘contemplate and endure the process of making new answers’. The earth looks upon us Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata created an environment that at once felt welcoming and restful, yet gifted me the space to think about fraught things. The mesh of earth, site and history referenced in the conversation between these artworks drew attention to the cultural limits of my own knowledge. There was a gentle urgency to this exhibition, drawing my attention to a multiplicity of erasures. Such erasures take place in the physical world – with the levelling of a mountain. They exist, too, in the histories that generations of immigrants to Aotearoa, such as myself, write in order to shape a comfortable relationship with the land that we occupy.

By bringing Papatūānuku, in various manifestations, into the gallery space, Harrison, Iti, Paul and Turei collectively encourage an interrogation of all sites altered by the process of colonisation and development. What are the histories that we choose to memorialize? What are the histories that we attempt to build over?

My right to stand on the earth of Aotearoa is not grounded in whakapapa or through a relation to Papatūānuku. Rather, it is governed by a colonial state apparatus which has allowed me, in my capacity as a British Citizen, to easily gain the legal right to exist in this country, on this land. The earth looks upon us Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata allowed me to feel a truth that I already knew: that my standing upon this earth is an act fraught with history, privilege and responsibility.

[1] Gabi Ngcobo quoted in ‘Gabi Ngcobo in Conversation’, Ocula, http://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/gabi-ngcobo/ accessed 9 January 2019

[2] Rawinia Higgins, email correspondence with the author

[3] Wall text for The earth looks upon us Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata, Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi

[4] Ngahuia Harrison quoted in wall text for The earth looks upon us Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata, Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi

[5] Ana Iti, quoted in wall text for The earth looks upon us Ko Papatūānuku te matua o te tangata, Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi

[6] Ngahuia Harrison, email correspondence with the author