TarraWarra International 2019: The Tangible Trace

The fourth TarraWarra International exhibition, The Tangible Trace brings into dialogue traces, routes and memories from across the globe. Curated by Victoria Lynn, Director at the TarraWarra Museum of art, the exhibition is a meditation on what traces are seen, not seen, unseen and projected. Featuring the works of Francis Alÿs, Carlos Capelán, Simryn Gill, Shilpa Gupta, Hiwa K, and Sangeeta Sandrasegar, each artist’s work is bought into dialogue with not only each other, but with broader imprints that experienced, felt or empathised with or recalled, are left behind.

It’s understandable that Lynn teased the exhibition’s concept out through a conversation with Melbourne-based Sandrasegar. [1] The artist’s practice has long been concerned with the making visible of the often unseen relationships through trade and migration, through the impact of colonisation, and through material exchange. Sandrasegar’s earlier work The scaffold called the Motherland spews infinite grace (2012) resulted from a trip to India in 2011 in which the artist was fascinated by the amount of Eucalyptus trees in the country—finding their way to India through colonial trade. The artist cast branches from the trees in brass, a material common to traditional Indian sculpture, and transported, or ‘returned’ these branches to Australia. [2] This work, much like the work commissioned specifically for The Tangible Trace, was concerned with what is seen, and what materialises from a sense of seeing.

What falls from view (2019) is a series of curtains lining the gargantuan halls of the TarraWarra Art Museum. Using Indian fabrics (khadi cotton), silk organza and cloth hand-dyed with Australian native cherry plants and indigo, the tall curtains are hung to obscure the normally most-Instagrammed windows of the building, which look out to the picturesque hills around the TarraWarra Estate. In their obfuscation, visitors are prompted to imagine beyond the windows, while the sombre Symphony No. 1 ‘Da Pacem Domine’ (1991) by composer Ross Edwards, creates an atmosphere of foreboding, but also of meditation. Viewers, depending on their own experiences of the site and its surrounds, and depending on their own concept of What falls from view, are forced to recall traces throughout their whole bodies—through every sense, and think it through in relation to Sandrasegar’s exploration of trade materialised. Close your eyes and imagine what stood here only 250 years ago, and how journeys (and memories) were made (and at times, erased).

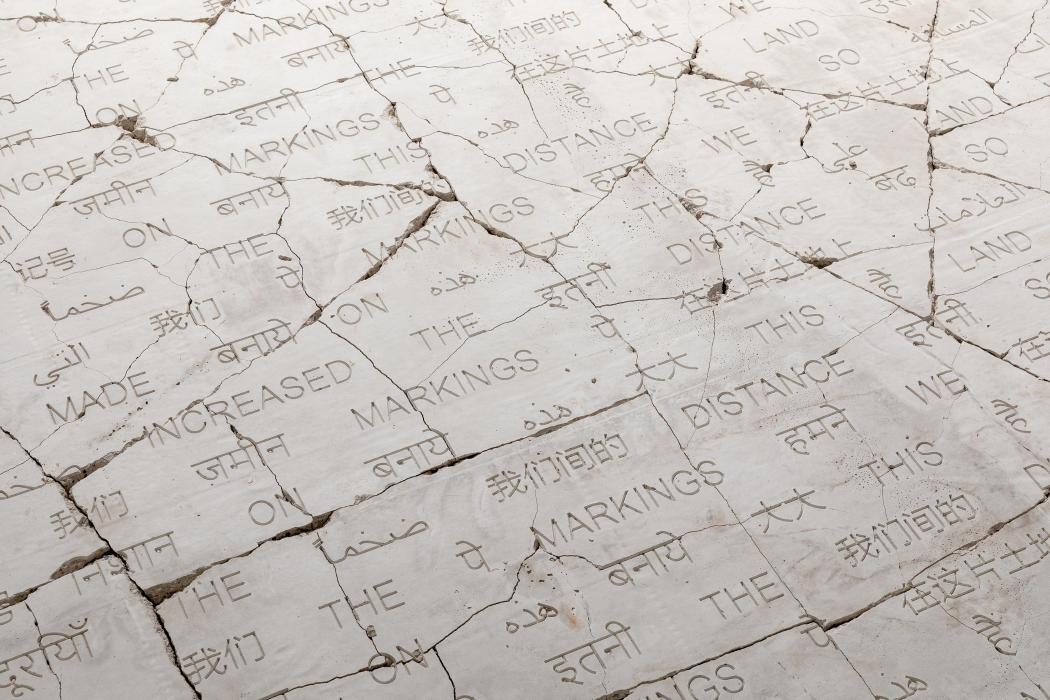

Indian artist Shilpa Gupta’s work similarly enforces a sense of your body in the space. In The markings we have made on this land have increased the distance so much (2019), the artist has engraved the title of the work translated into four languages—English, Hindi, Arabic and Chinese—repeatedly on a slab of concrete. The concrete is broken into small pieces, some the size of a golf ball, others a small loaf of bread, and at the exhibition’s opening weekend, visitors were invited to take pieces of the work home with them, thus creating a new kind of trace, from a work whose interpretation is one of poetic anti-colonialism, a zooming in and localising, and also a broadening in regards to globalisation. It would have been nice if Gupta had been permitted time and energy for a new commissioning of this work which included a translation in the local Woiwurrung language (of what can be known), as the exhibition’s explanation of the work focuses on the marks left by invaders and felt by First Peoples. [3] Visitors will once again be invited to take pieces of the work with them as they leave, at the closing of the exhibition. [4] Would a redistribution to a site suitable for the material to further break down have more intended effect than sitting on a mantelpiece? What will be left on the gallery floor when the exhibition is over?

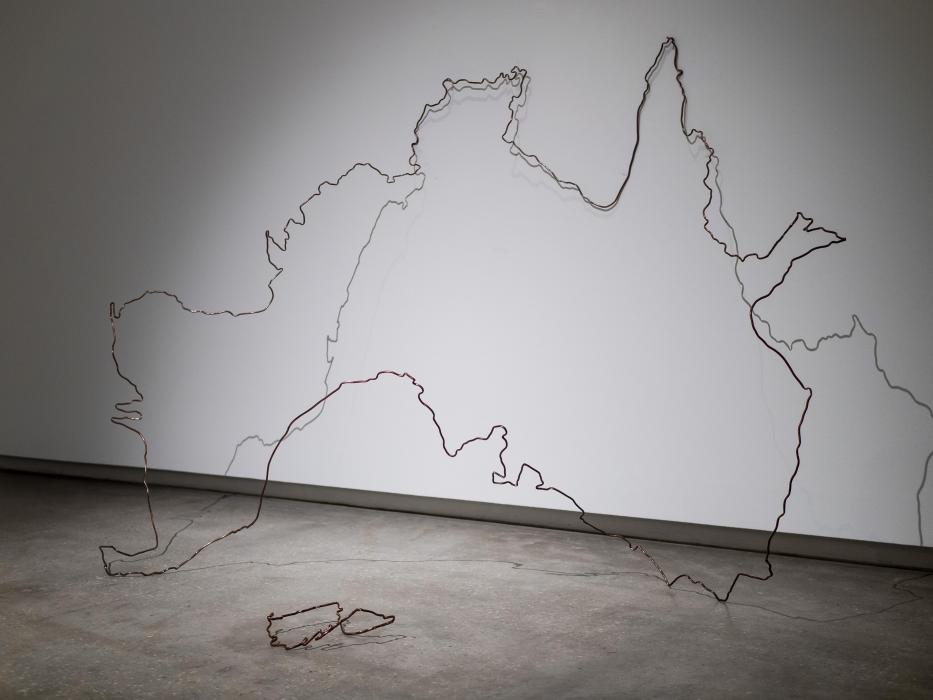

Specifically commissioned for The Tangible Trace, Map Tracing #7 – AU (2019), a work that is reiterated for and with different contexts, sits alongside Gupta’s aforementioned work. The artist has manipulated copper piping in order for audiences to see the work in different formations from different viewpoints. Its materiality is apt, in that copper is an element known to prevent sperm from entering the cervix, and repel slugs and snails from garden plants, an apt metaphor for themes around borders, nationalism, patriotism and belonging.

Hiwa K’s video, Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) (2017) draws another kind of trace all by itself—a chaotic trace through the many mirrors the artist balances on his nose as he retraces the journey he made from Kurdish Iraq to Europe. Narrating throughout the 17-minute film, he poses questions on the perceptions of migration, on religion, on language, listening, citizenship and groundedness. It’s wry and thoughtful; the most pertinent quote comes when he is asked ‘where are you based’ and he replies ‘on my feet’. Originally commissioned for documenta 14 (2017), in a highly contentious exhibition in an equally contested environment, the video also critiques the art world itself, questioning its legitimacy in a time of global inhumanity, relating Western art history (as the canonical global history) to a sense of unease—a burden. It’s visceral and curious, and the artist’s genuine questioning makes it all the more humble.

At entry to the gallery, you’re faced with a set of vitrines containing fragments of rock and clay gathered and created by artist Simryn Gill. The work, Domino Theory (2014), uses two types of materials in its display; pieces of detritus—bricks and odd earthenware fragments found by the artist on the beach at Port Dickson, Malaysia, where she is partly based and which is also part of a major shipping route, and other objects crafted by hand from earth excavated from termite mounds in the same area. Each piece has its own trace—its own story to tell—and combined they create a cacophony, together. The title references a term that was used to describe the feared domino effects of Communism in the 1950s through the 80s—fragments colliding into a whole which under Western eyes would be a catastrophic regime. Used as a title for this work, and in relation to these fragments contained together, it’s a pertinent statement on the ways in which history and globalised trade have created our current times and how maybe capitalism and the colonisation that allowed capitalism to thrive is not looking so great after all. The hand-made objects also question how traces can be made, remade, undone—coming from a natural phenomenon and their size depending on the size of the termite mound, they create memories of the natural world intermingled with the industrial world. Gill’s photographic works, Passing Through (2017-ongoing) sit across from the vitrines. These photos document crumbling remains of what was once a high-end hotel. Each photo holds memory within its mimetic representation, an imagination, and a perpetuity.

Francis Alÿs’s video installation, Paradox of Praxis 5: Sometimes we dream as we live & sometimes we live as we dream, Ciudad Juárez, México (2013) is tucked in the back corner of the gallery. The artist is known for his walking expeditions, and here, is featured kicking a flaming soccer ball through the border town of Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. The symbol of the ball on fire talks not only to the violence that has beleaguered the city, but introduces a sense of frivolity.

Skewing tradition, Carlos Capelán’s paintings collate human forms against geometric, abstract backgrounds. There’s no telling where the eyes are looking, where the limbs are going (or whether they’re going anywhere), and the multitude of the figures allows different tellings of the stories you suppose that they have. Capelán fled Uruguay in 1973—the year of the Uruguayan coup d’état—these figures are strewn across the canvass, seemingly not knowing where they’re going, but also not knowing where they are. The most affecting of these paintings, in the context of the [white cube] art gallery, is Self-Portrait as a Museum (2019), featuring a quasi-architectural plan of a gallery containing anguished faces, and accompanied on the right by a portrait (perhaps a self-portrait) surrounded by outlines of austere-looking men, on a patchwork background of geometric patterns. A simple text reads ‘Art is in any museum’. The series, Implosions (2018-19) was commissioned specifically for the exhibition.

Together, the works, as in Gill’s fragments, all trace across each other; just as trade routes, histories, wars, allegiances, great loves, allegories, and problems to overcome are lost and living memories that can be recalled or reinterpreted. Lynn states in her catalogue essay that ‘If everything is a trace, then nothing can be universalised, but also, if everything is subject to its absence, through its not being there, there is always a slippage of meaning.’ [5] The slippages create the curiosity that keeps the world turning.

[1] Lynn, V (ed), 2019, The Tangible Trace (exhibition catalogue), TarraWarra Museum of Art, Melbourne, p9.

[2] Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2012, “The scaffold called the Motherland spews infinite grace” (online). Cited 21 July 2019 <https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/281.2012.a-h/>

[3] “These words carry with them the suggestion of the colonial encounter: the ‘marks’ made on the land have the effect of increasing the gap between First Peoples and their invaders.” Exhibition panel accompanying Gupta’s work, The markings we have made on this land have increased the distance so much (2019).

[4] Visitors are encouraged to take and rehome a fragment of Gupta’s work from 8th August 2019 till the exhibition closes on the 1st September 2019.

[5] Lynn, V (ed), 2019, The Tangible Trace (exhibition catalogue), TarraWarra Museum of Art, Melbourne, p11.