Stop Peeping

Love and desire have been philosophized, celebrated, memorialized and lamented for time immemorial. Theorists, musicians, and artists alike have oft-commented on love and its ability to push us towards psychological extremities and irrational behaviour, perhaps even to the extent of collecting the sweat of those we lust after to freeze into ice lollies for consumption.

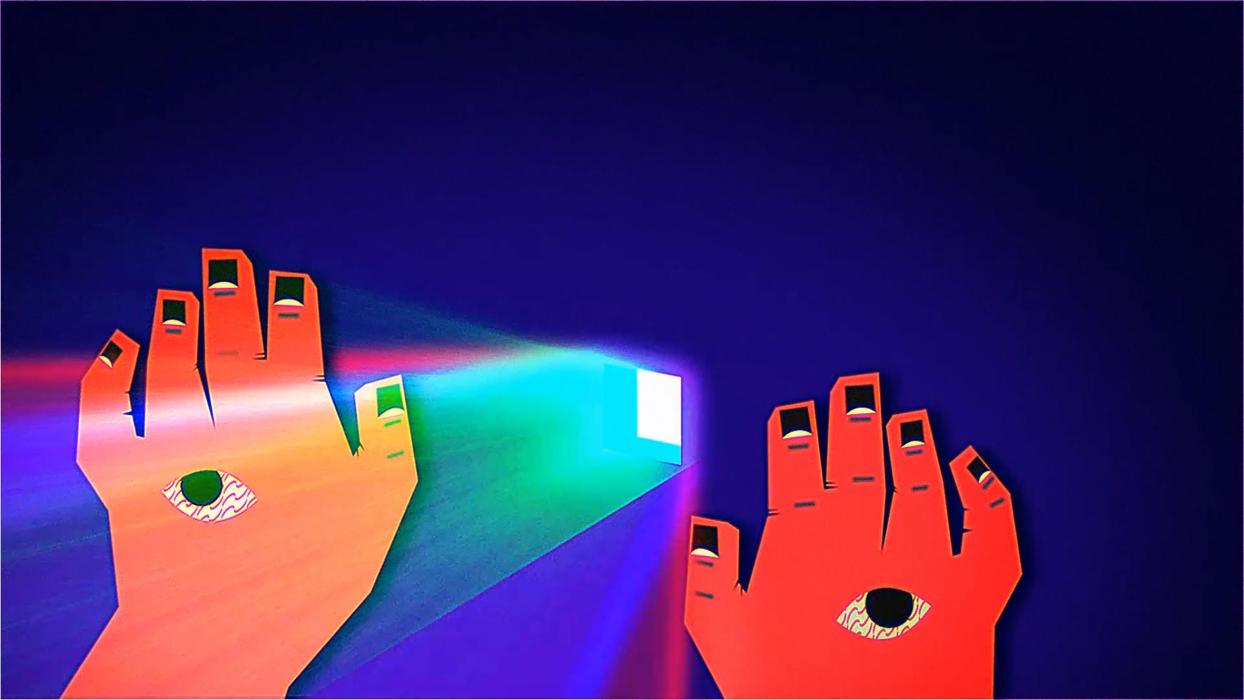

It is this bizarre act that the male narrator in Wong Ping’s animated video Stop Peeping (2018) commits as he spies on his new neighbour through a hole in the wall of his apartment. The titular work of Cement Fondu’s latest exhibition of five Asian and Asian-Australian artists exposes the complex paradoxes of desire. The bright pastel palette of Wong’s lo-fi, retro-pop video is reminiscent of the graphics of 1980s and 1990s Nintendo games, subverting the more troubling and perverse narrative recounted. As the narrator’s lust grows, he breaks into his neighbour’s apartment and collects the sweat from her hanging clothes. Broadcasting this narrative in the public realm of the gallery reveals that whilst love and desire may be viewed as private matters, they are shaped socially and publically. As theorist Judith Butler acknowledges, our sexual desires derive from “the desire to be known.”[1] That is, our desires do not originate from our personhood but rather through social and political norms, an idea taken to its extreme in Young Hae Chang Heavy Industries’ (YHCHI) video installation Cunnilingus in North Korea (Tango Version). YHCHI’s video is an imagined political address by Kim Jong-Il, North Korea’s Second Supreme Leader (1941-2011) in which he absurdly defends communism by advocating for the sexual satisfaction of North Korean women. In this irreverent work, love, desire, and sexuality are not removed from politics echoing Michel Foucault’s observations that sex historically has been under the modern state’s control.[2] Stop Peeping reminds us of the latent perversions and fetishes that exist beyond closed doors and drawn curtains.

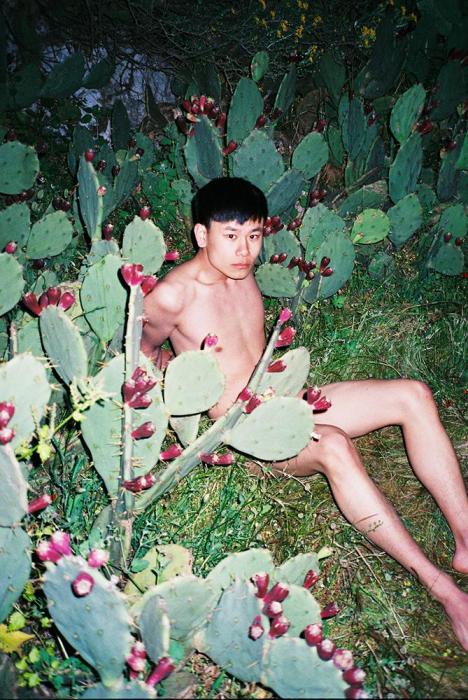

In fact, curtains have been hung throughout the gallery so that visitors must weave through them and peak through the translucence, creating a milieu of secrecy and clandestine rendezvous. The otherwise cold, concrete interior of Cement Fondu has been transformed by sensuous pink lights. The private and the public imbricate as visitors are made to feel like voyeurs, accentuated by Ren Hang’s photographic series Untitled (2015). In one of Hang’s photographs, the eye of a young woman surreptitiously peeps through two rock walls, the harsh rocks framing her bare skin. Her gaze is one of curiosity and enticement but as she looks directly at the camera, it is also a challenge to the viewer. We participate in the act of voyeurism—in viewing art we are glancing and glimpsing at artists’ internal worlds.

Our role as viewer/voyeur is enhanced by Po Po’s three soft sculptures that are displayed alongside Hang. In Erotic (1982-1986) two pink pillows are intertwined on a black kapak mat, suggesting the bodies of two lovers. As art historian Briony Fer asserts soft sculptures like Po Po’s operate via a “language of anthropomorphism, of bodily projection and empathy. Bulbous forms, organic forms [seem] deliberately to inscribe an erotics of the body.”[3] This is further seen in Three Graces (1986-1996) where three phallic structures or ‘arms’ tentatively reach upwards, their soft blue folds of silk reminiscent of wrinkled skin. Such tactile, material objects speak to our haptic vision, acting as a counterpoint to the virtual digital worlds of Wong Ping’s video, Hang’s photographs and YHCHI’s video.

Po Po’s sculptures ostensibly embody erotic love, yet their sensuality articulate broader themes of love. Indeed, Jason Phu’s installation red is the colour (of love) of the fire that cooks the food we eat. newspaper is the colour (of nostalgia) of the smoke in our eyes and in our lungs. in the future there is (transparency) no colour, only various shapes (2019) creates a multi-dimensional understanding of love away from the reductive singular narrative of romance permeated in popular culture. Separated into the mezzanine area, Phu’s installation speaks instead of filial piety as his parent’s recount how they met and how Phu’s grandparents met. Here love is experienced culturally and generationally. Phu’s inclusion in Stop Peeping mirrors the amorphous and subjective nature of love.

Considering that our emotional patterns in intimacy are socially and culturally cultivated, what is the significance of showing these Asian and Asian-Australian perspectives? Is love, sex, and desire somehow different for Asians? No doubt sexuality for Asians is racially fraught as femme bodies are often hypersexualised and fetishised. Or, antithetically, as Hang observes the global “impression that Chinese people are robots” persists.[4] Ultimately however, this racialised framework was perhaps unnecessary, as it was subsumed by the visceral, sensory, and emotional works informed by our universal desire to keep peeping.

[1] Judith Butler, Subjects of Desire: Hegelian Reflections in Twentieth-Century France (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987), 137.

[2] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction (New York: Vintage, 1978).

[3] BrionyFer (1999), ‘Objects beyond Objecthood’, Oxford Art Journal 22(2), 29.

[4] https://www.bjp-online.com/2017/02/ren-hang-leading-chinese-photographer-has-died-aged-29/, The British Journal of Photography, accessed 23 March 2019

...,%202019.%20Mixed%20media%20installation%20commissioned%20by%20Cement%20Fondu.%20Courtesy%20the%20artist.%20Photo%20Tim%20da-Rin_1-itok=hbHfk0sN.jpg)