Silent Aspiration

Using the materials associated with contemporary working life, Tim Woodward’s exhibition Silent Aspiration at Outer Space, Brisbane, investigates the blurring boundaries between leisure and labour, highlighting tensions between professionalism, labour casualisation, productivity and boredom through a predominantly aesthetic lens. Woodward seems to veer clear of making political statements about the broadening scope and conditions of employment. Instead, he looks at more subtle material differences, hinting at speculative individual narratives, and how these reflect a changing relationship between work and lifestyle.

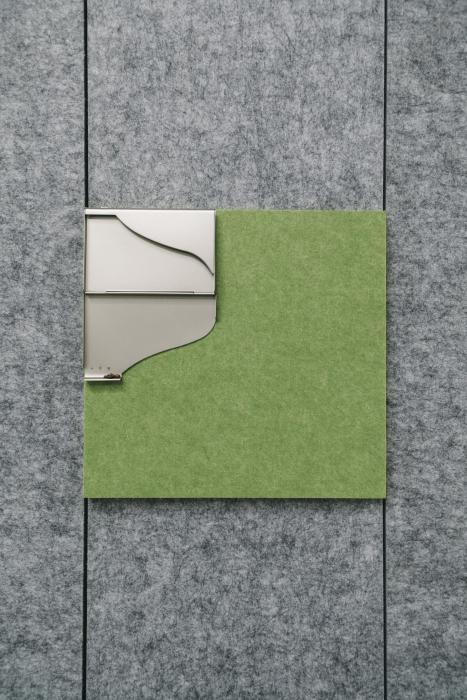

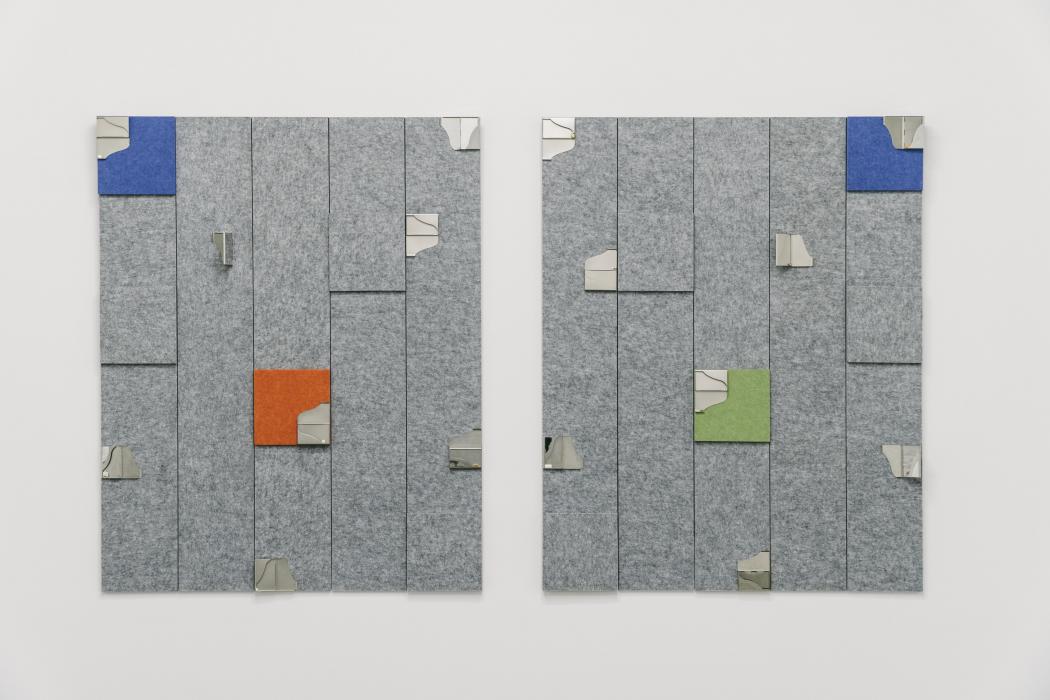

Woodward’s sculptural assemblages primarily use objects recognisable for their corporate aesthetic. In the largest wall-based assemblage, Silent Aspiration (Conglomerate Gulp) (2019), Woodward creates a canvas using layered rectangular PET acoustic panels—the kind that line office partition walls to dampen distracting sounds and conversations. A number of the PET panels are arranged on top of a grey backboard in cheery corporate colours—lime green, burnt orange, blue—giving them the look of a corporate felt Mondrian. Mounted on top of the panels are shiny stainless-steel business card holders splayed open, with tiny commonplace objects nestled in their corners. A breath mint, a spare button, a multivitamin, a Nurofen headache tablet, a small round battery, a sunflower seed, pistachio shell and a shrivelled goji berry, all small enough to be swallowed.

The contrasting textures of the PET panels and slick silver cardholders reflect a familiar office workplace design ethos. The tiny objects resting in each of the card holders give the impression of personal narratives existing within the anonymous corporate office, combining the clinical, uniform textures of offices with the detritus that accumulates when people occupy it. Many of these items could function as private daily coping mechanisms, intended for convenience, comfort, or to increase productivity. Their inclusion acts like narrative seeds into the lives of imagined anonymous office workers.

In the work Grouphead (2019), Woodward again uses assemblage to imbue objects with narrative. On a semi-circle shelf mounted on the wall sits a glass espresso cup decorated with garish orange and yellow flowers. What seems to be a metal door handle emerges like a shark’s fin from the dark, sticky-looking coffee inside the cup. Woodward later told me that this object is actually a laryngoscope blade, an instrument used to examine the larynx. From the materials list we learn that this work consists of a ‘double espresso two sugars prepared in a corner kitchen stirred with an indirect view of the vocal cords.’ Grouphead continues in the vein of a number of Woodward’s assemblages under the same title that follow the formula of ‘cup of coffee prepared / in a way / by a person / with object / etc.’ By conjuring the familiar activity of the coffee break, Woodward focuses on the in-between moments that balance on the threshold of work and leisure, productivity and rest.

In the work Silent Aspiration (Conglomerate Gulp), Woodward’s selection of objects suggests an upper middle-class experience of professional work; goji berries, pistachios and an Alpha 60 brand button conjure visions of a health-conscious arts administrator rather than a stereotypical white-collar office worker. This inferred middle-class perspective and aestheticisation of office work, is juxtaposed against a video work in the exhibition, Sleeping Under a Motorcycle not Sleepy (2019), which focuses on an off-duty food delivery driver, a precarious gig-based profession often undertaken by students and people working multiple jobs.

The video shows a man lying on a mat on the floor of a white space, a gallery or studio, with an impressive shiny black motorbike propped up behind him. A familiar boxy insulated backpack sits to the right. The man, dressed in black, rests his head on a cushion while watching something on his iPhone. He wears colourful patterned socks, like the ‘Happy Socks’ brand sold at department stores, and in a close-up shot the viewer sees him tapping his foot in the air in a carefree way. He is depicted at rest, taking a break or waiting for his next delivery request. Indeed, this relaxed scene seems in opposition to my perception of what independent contractor work looks like.

Using smartphone apps, tech start-ups like Deliveroo, UberEasts, and Foodora offer fast delivery of food from restaurants in a user’s area, drawing on a pool of drivers or riders who can accept these one-off jobs. These service providers often use an independent contractor model, allowing them to avoid paying regular employee entitlements like annual leave, sick leave and superannuation. The model offers drivers the freedom to accept the jobs they want to, but being an on-demand service, there is no guarantee of minimum earnings despite being on-call. This kind of insecure work is part of a labour market in Australia that is increasingly precarious and laden with personal risk.

Sleeping Under a Motorcycle not Sleepy looks at the disjointed downtime between jobs that has become symptomatic of twenty-first century labour. Workers who are on-call to perform short tasks in response to demand—and payed only for these one-off services—are forced to seize the in-between moments for rest and leisure. I have witnessed these moments in play outside of a busy McDonalds in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley: a couple of young men, sometimes some women, casually hanging out, leaning on their bikes, sitting on the pavement, chatting together, or watching their phones. Woodward’s tableau seems far removed from this context.

This driver lays on a padded mat in a clean indoor space instead of on the street, with a nice motorcycle instead of a bicycle or scooter. The work seems to aestheticise the casual aspects of labour casualisation, without acknowledging the potentially exploitative conditions that come with it, like low, unreliable pay, no employee benefits and the pressure to provide speedy service under threat of a bad rating. To me this exposes a disconnect with the realities of engaging in this kind of work, however Woodward may instead be portraying a different challenge of contemporary labour markets: underemployment. If a middle-class person engaging in precarious, gig-based work seems unusual to me, perhaps this simply reflects my privileged social context and the context of my city, in which the middle class is yet to be heavily impacted by gentrification, rising rents, or high costs of living.

Combined, the works in Silent Aspiration comment on the differences between stable employment in designated workspaces and more precarious gig-based work that can be undertaken anywhere. Interestingly, in both of these contexts Woodward chooses to focus on the time at work spent not working, conjuring narratives of boredom and attempts at personal comfort—autonomy under the distantly looming imperative of productivity. The works also conjure disconcerting perceptions of class distinctions between those who participate in administrative and service labour. While Woodward’s interest in the corporate is acutely aesthetic, the longer a viewer spends critically engaging with the works and unpicking the uncomfortable aspects, the more challenging questions arise.