Octopus 19: Ventriloquy

The 17th century English diarist John Evelyn described a party at a friend’s house in which the host played a cruel trick on his guests. Constructing a hollow statue, the host attached a concealed hose allowing a servant to speak through the statue from a great length. The effect on the guests was, by Evelyn’s account, both humorous and horrifying in equal measure.

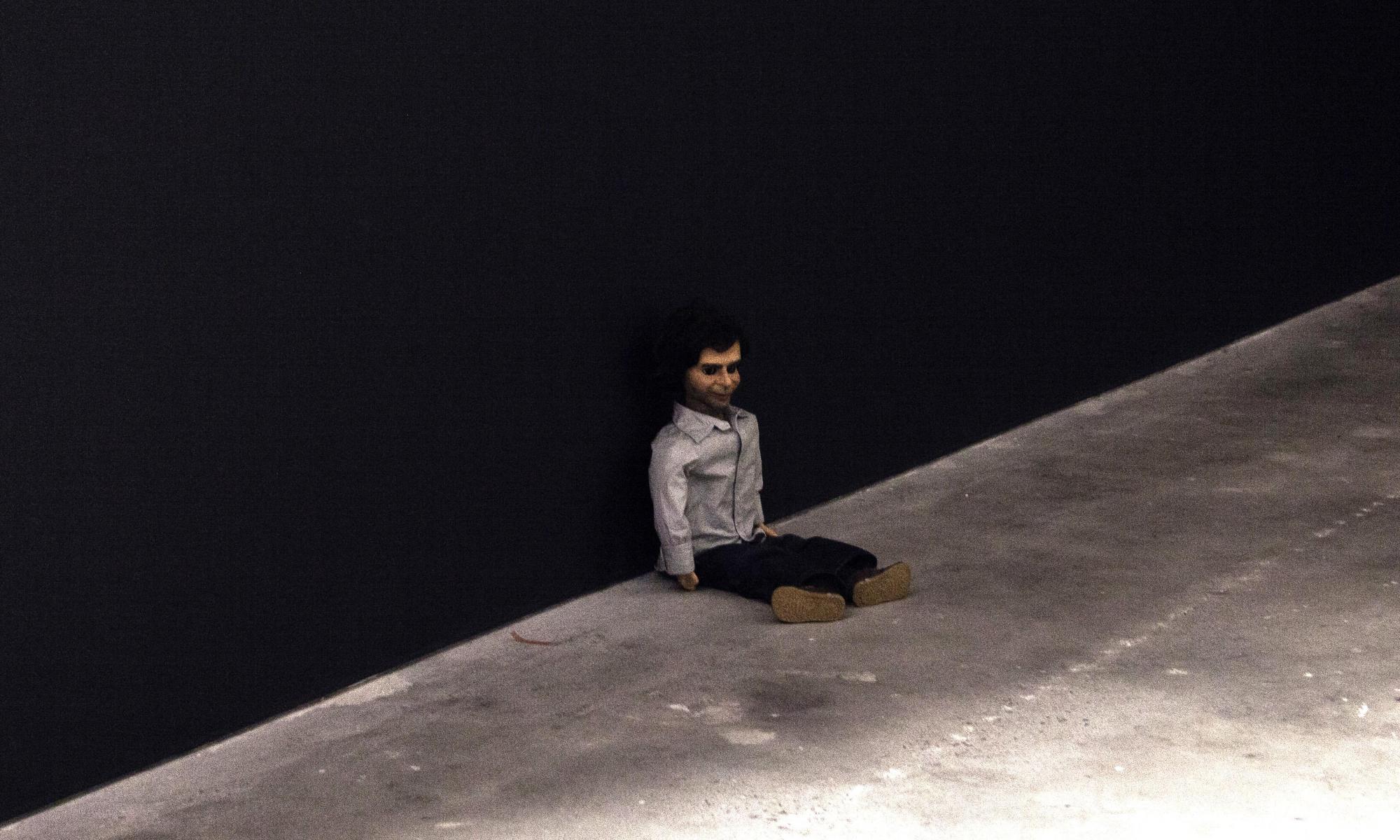

Such dark entertainments interest Joel Stern, curator of Ventriloquy (Gertrude Contemporary). With a cultural history rich in comic abuse, the practice of ventriloquism is vaudeville in its origins. The ‘vent’—often the straight man to the wry and witty dummy—deceives, distracts, and divests. The ventriloquist is a confidence artist, diverting attention away from the twittering lips, diverting us to their more outrageous wooden ego-child. Charlie McCarthy, the urbane tuxedoed dummy to the dry Edgar Bergen; Archie Andrews, the naughty schoolboy to the dull Peter Brough; and my personal favourite, the abrasive and abusive Charlie Brown to the mute Arthur Worsley.

Ventriloquism is much more than the practice of vent and dummy, and Stern imagines the art of the vent as an extended metaphor for a broad range of social, cultural, and political distractions. Imagined as a set of strategies employed by a range of artists to animate the object (Simon Zoric, Ceri Hann), dissect the bureaucratisation of voice (Eric Demitriou, Danielle Freakley), and dark humour Ventriloquy explores new contracts of consensual self-deception.

To take, for example, Demetriou,’s That Syncing Feeling. Installed in the middle of Gallery 2 stands an empty booth, the type purposefully designed to enable simultaneous translation. Empty and locked, lights intermittently strobe, perhaps awaiting the beginning of a political debate, or the interrogation of an international tribunal. The empty translator’s box is an Echo without a Narcissus. In ventriloquial terms, this is ‘far ventriloquy’—convincing us that somewhere inside the box is a voice, struggling to be free. We go to the box, only to find it empty. We’ve been duped. The presence of an old wooden hobby horse on top of the bureaucratic booth is no distraction, the folly is an entertainment, a trick played on children.

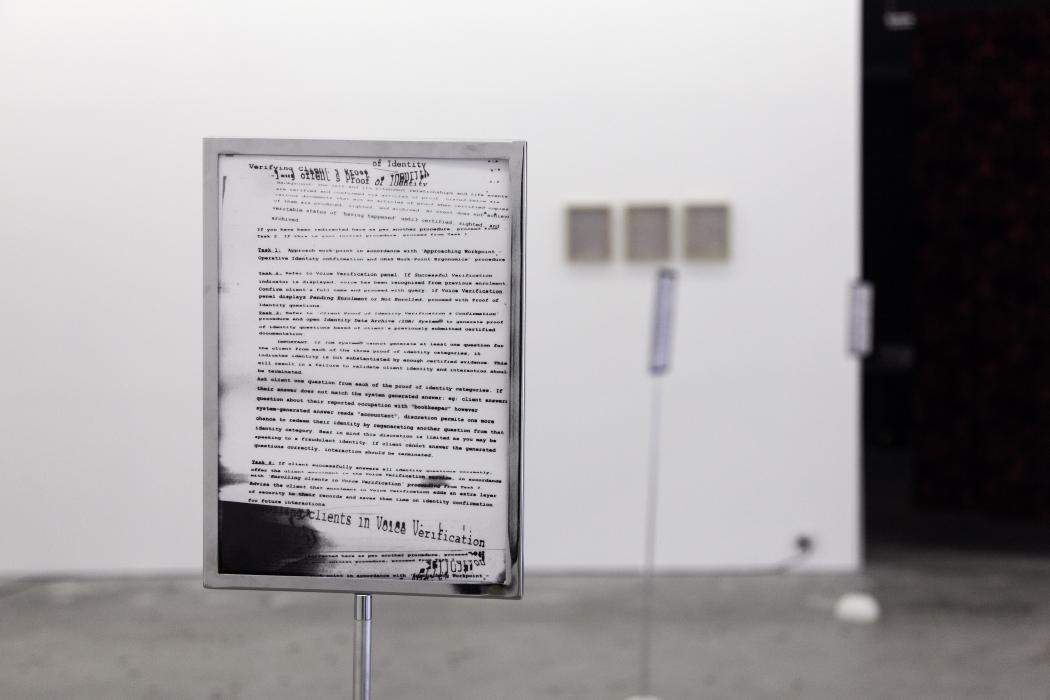

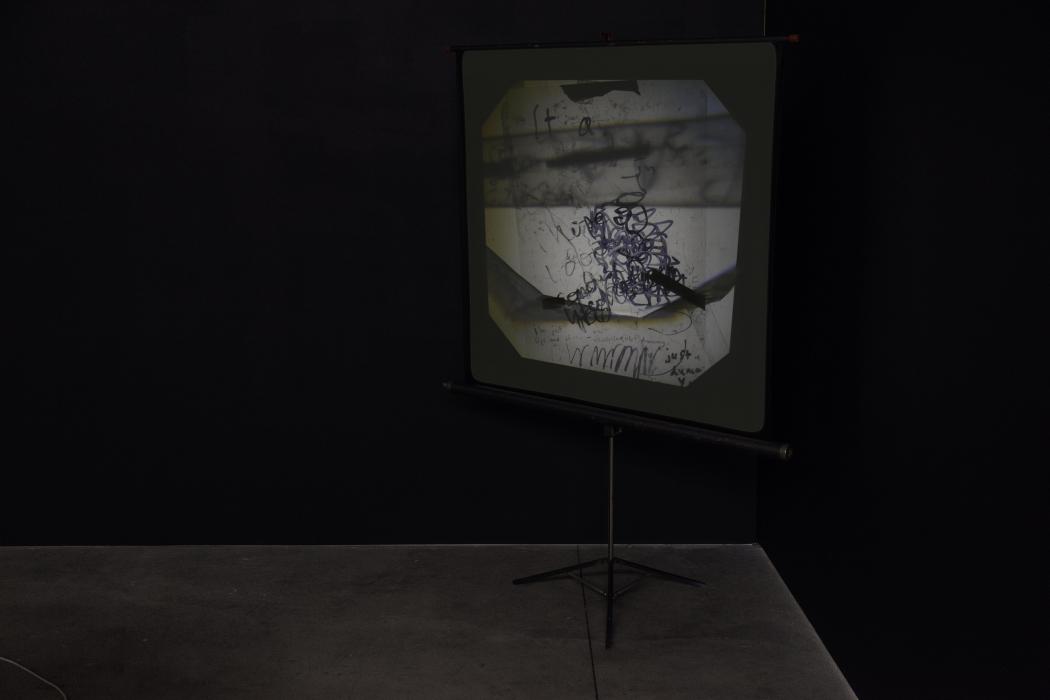

Ceri Hann’s Money Talks consists of scattered and defaced coins throughout the gallery spaces and a concentration of coins present via overhead projector. Money does indeed talk, and it also demands us to speak. Telephone banking voice identification, the ATO automated voice recognition—also picked up on in a different work by Gabrielle D’Costa—means we have to speak to access our own cash. And the more we have, the more we have to say.

Some works address the deceptive voice directly, though all have in some way or another a secret they seek to keep hidden. Makiko Yamamoto’s two-channel video installation Ego as Echo examines what is known in linguistic psychology as the McGurk effect. Ventriloquy plays out a tension between our lips and the words that they form. Ventriloquists rely more on deceiving our visual verification than they do on the authenticity of the sounds produced. Yamamoto presents us with the visual, whilst George (their AI alter-ego) presents us with the words. As the video proceeds, it is George that is the convincing, the natural. Yamamoto becomes redundant; the dummy mutes the vent.

Jacqui Shelton’s Crush video and installation (I missed the accompanying performance) presented us with the central conceit that underpins power. Unable to breathe, sweating bodies, faintness rising, intense claustrophobia. Are we describing love, or a riot? Hung on a steel barrier—as you might see kettling protestors or protecting politicians’ thoroughfares—Crush is intense sensation and a total loss of control. Like capitalism perhaps, to be loved demands that we let love in, that we divest. To feel a ‘crush’ is to lose our sense of groundedness, and Shelton’s video blurred that line between the breathlessness of a first kiss and breathlessness of a jackboot on the throat.

Not all works were as loud. Steven Rhall’s subtle Aboriginal Art Affects is as simple as a ribbon flittering in the air-conditioning. Activated when passed underneath, its simple tongue flitters around chaotically. Amongst the noise of the surrounding works, it could be easy to miss. In the silent interludes it’s the loudest voice in the room. It is, as the title suggests, an affecting take on the presence and absences of voice.

The subtitles of Ventriloquy’s extended performance and event timetable attest to the scope of such diversions: self by proxy, the puppet’s freedom, lifenessness, anachronism affects. The temptation to take us down the dark alley of deconstructions and structuralist pyrotechnics is held—like the dummy itself—wisely at arm’s reach. Though the spectres of thought—it does matter who is speaking, someone once said—are strong, and there is strong sense of playful and poetic. The comedy is there, though it's dark. And the dark voids were there, in the comic fringes.

Ventriloquy is an extended metaphor for the life and afterlife of the voice. The ventriloquial voice is, perhaps, symptomatic of the ‘modest witness’ that Donna Haraway puts forward as the foundation stone of Modernity. The collapse of our subjectivity into those objectivities of the dummy, our ever-present witness, Haraway argues, turns mirrors into lenses and lenses into mirrors. It is perhaps in this ethical platform that the exhibition pushes beyond the limits of the contemporary. As an examination of the frameworks of diversion, deferral, divestment, dummying, Alexa and Siri, the exhibition situates itself at an unusual crossroads.

Jordan Peele's latest movie Us plays out a scene in which the Alexa-like ‘Ophelia' is commanded to call the police. Instead, Ophelia plays NWA's ‘Fuck the police.' With AIs increasingly called on to report and record, their legalistic function is a terrifyingly real prospect. Joel Stern's careful examination of these acoustic jurisprudences reminds us that the success of any ventriloquy is to believe that the dummy is real.

1-itok=DfaWQXb0.jpg)