Nosferatu on Reddit: Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun

Stepping into Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun (2015) is like penetrating a hi-gloss sepulchre funded by Germany’s diplomatic aspirations for the 56th Venice Biennale. Here lies a video with the romantic stench of a corpse, a cadaver that once held the spirit of the ‘year 2015’. Like a body that has begun to decompose, it is easily torn apart due to its didactic gestures: the global circulation of pixelated images in a post-Internet future that began to date ‘five minutes ago’. The work is not old enough for one to proclaim it dead, yet, it looks like it perished a long time ago. In this manner, it appears to inhabit the tenebrous zone of the undead, where soulless creatures like Nosferatu roam without a heartbeat. Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun (2015)—a video premised on a fiction about the commodification of sunlight—strikes me as a vampiric text for several reasons. The plot itself suggests an anxiety regarding sunbeam that is hilariously reminiscent of the undead, for which the control of the sun would be the most unattainable ideal: one can easily picture a vampire seeking to commodify, tame and control daylight under the guise of entrepreneurship (the latter allowing it to pass as human). On the other hand, this capitalist project is vampiric as it feeds on workers and natural resources to the point of exhaustion. Like the masquerade ball in the film What We Do in the Shadows (2014), Factory of the Sun is redolent with references that once held a pulse, but now palpitate with critical faintness. Only three years have passed since its original release, yet, the images in the video seem to have travelled oceans of digital time to find us. Here, I look at this antiquated atmosphere through the lens of the vampyr with gothic pleasure rather than critical disdain.

Steyerl’s video is installed in a room gridded with blue, neon lights that reference the recent revival of early video game graphics. While such an environment should ‘pump’ one up, the impression is more akin to a tomb designed by a Tron enthusiast drinking cans of Red Bull to cope with the dreadful sentiment of feeling-dead-inside. Once full of vigor, Steyerl’s video projection now hangs exhausted, limb and inert in a metal structure that ironically (since voices in the video are hard to discern due to a lack of proper sound) resembles the stage of concert arenas. Same as Dracula’s uncanny English, the work speaks a language that is legible yet stands out for its antiquated mannerisms (on my second visit, I wore black to express my grief). In Amelia Winata’s review of the work on MEMO, she argues that this rapid datedness is the fatiguing effect of younger artists imitating Steyerl’s work. Considering that post-Internet art is largely premised on its own endless replication, Winata’s view brings a literal meaning to the idea of ‘going viral’—as this proliferation has consumed Steyerl’s corpus like a disease. This post-Internet vampirism is vastly more self-aware than zombie formalism (which is briefly mentioned by Steyerl in the prelude to her video) but equally monstrous and insatiable.

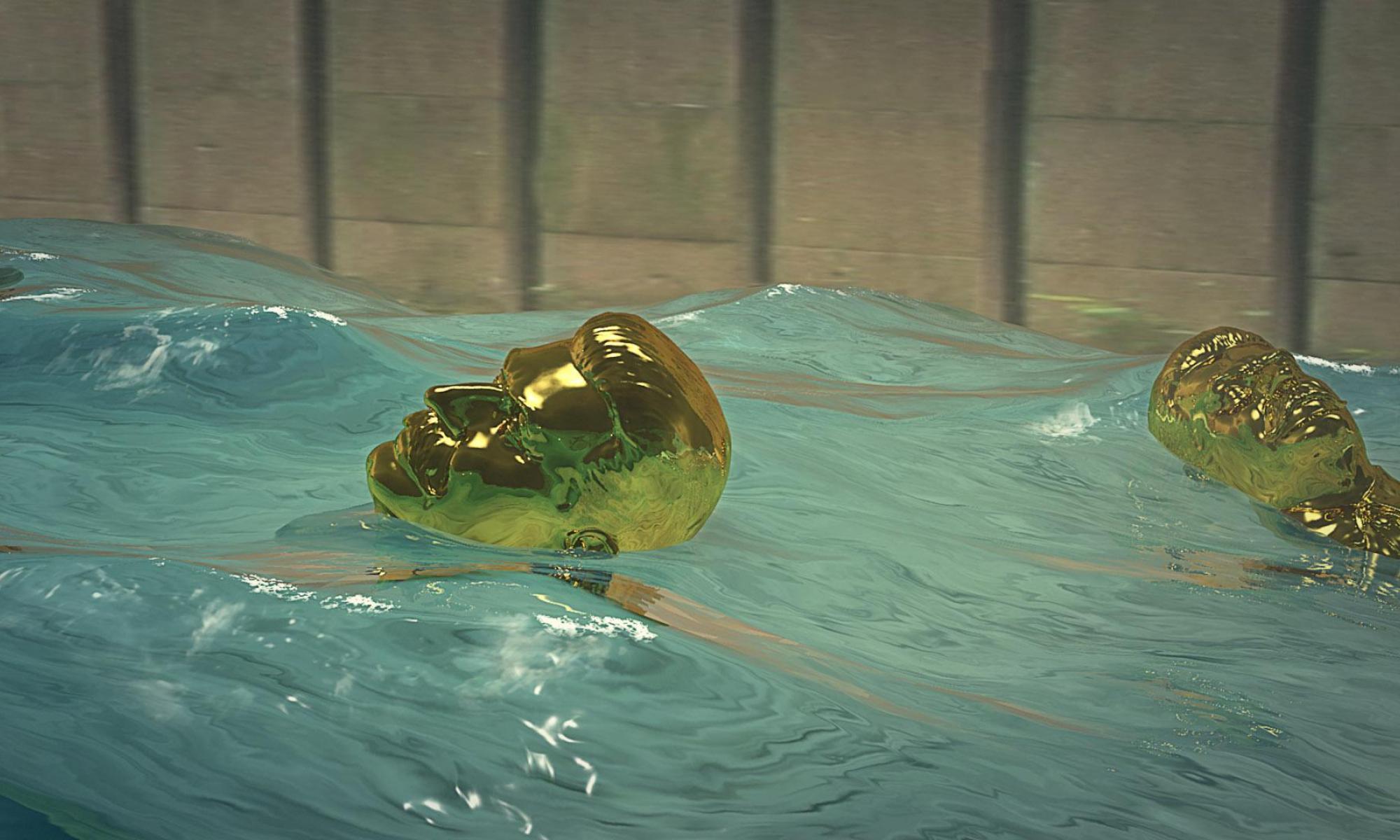

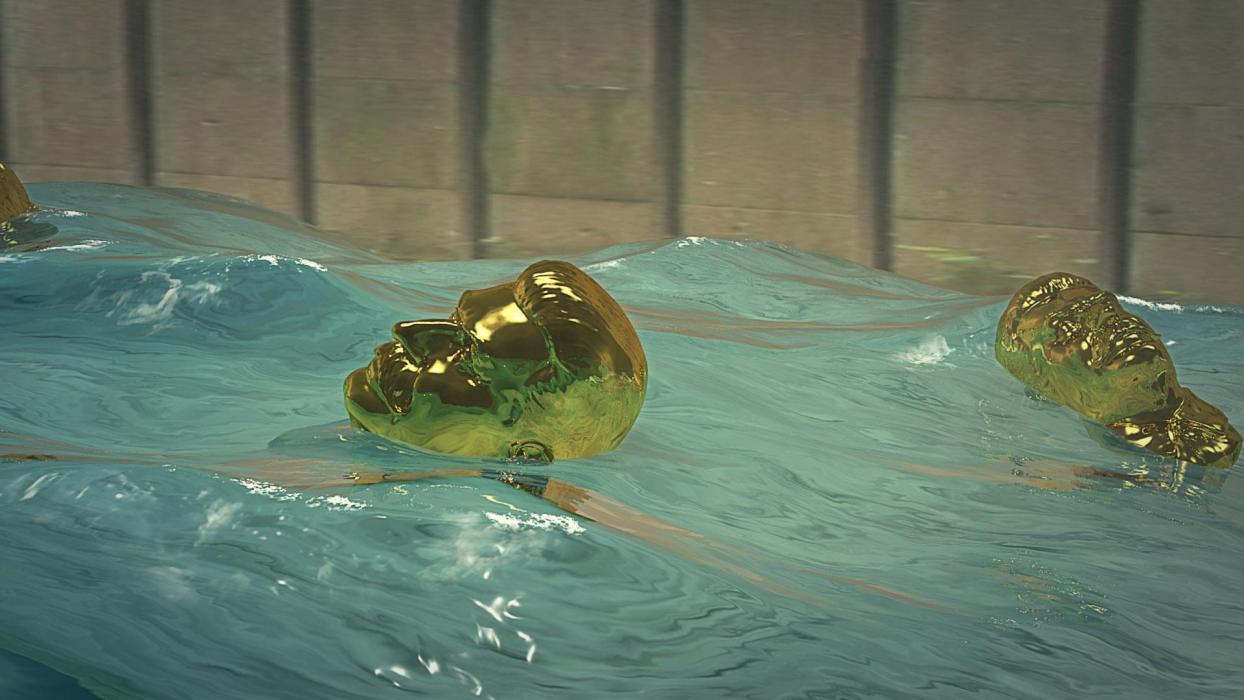

Factory of the Sun weaves a narrative about a dystopia where (young and hot) workers generate artificial light by performing (sexy) dance moves. This premise allows the artist to reference an eclectic array of moving image practices, ranging from YouTube videos to drone footage and anime avatars to point and shoot video games (often featuring the disembodied head of Stalin). These montages are interwoven with the real-life story of (Steyerl’s assistant) Yulia and her brother—who became a YouTube sensation after recording himself dancing in a golden bodysuit. The original footage is included in the film and unsurprisingly, was recorded in the ‘average (middle class) bedroom’ that typifies YouTube clips. Steyerl also incorporates hysterical anime vectors made by fans to imitate the movements of the YouTube star (which are admittedly quite mesmerizing). In this way, the artist links several associations that sit alongside each other like a Safari browser, where multiple tabs and windows (as well as ‘private windows’) accumulate and overlap to create a browsing history.

This method also echoes the logic of a Reddit thread, where users expand upon an initial post to create a network of nodes where images, stories and events find a central point. Like Steyerl’s modish gestures, these Reddit posts are encoded with the subcultural style of ‘the Internet’, where initialisms and memes collide in a network of Instagram depression, morbid Googling and online Pizza Hut orders—bringing a bottomlessness to the flatness of the Mac screen. Anime is a common cypher in this web, as it connotes the state of enclosure, shutdown and isolation (as well as Vitamin D depletion) that one expects from a committed Reddit user. The formal qualities of this generative flow (ongoing exchange of videos, intimate provocations and personal lives) seems to be mimicked by Steyerl to engross the viewer in a spectacular zeitgeist. This strategy is somewhat vampiric, as she appears to immerse herself in Internet culture to swallow its currency and satiate her practice. One gets a strong sense from watching Factory of the Sun that the artist has spent countless hours aimlessly feeding her scopic ‘hunger’ online as she crosses airports for a Biennale, rides an Uber to a conference and procrastinates on a student’s paper.

Rather than aging quickly, one could say the issue with the work is that it has not aged at all. Once impossibly current, her video encounters a premature death just as the character of Claudia in the film Interview With The Vampire (1994), who is bitten by Lestat (perhaps the equivalent to blockbuster events that consume artists such as the Venice Biennale) as a child and thus, lives eternity under the guise of an infant. Factory of the Sun establishes intertextual relationships with such degree of specificity and discursive modulation that it creates a state of intense self-enclosure. In other words, it latches excessively onto the zeitgeist in a way that prevents it from evolving further; closing the entrance to new meanings and relations by framing every sign with a didactic border. The artwork—like Claudia—is frozen in the eternity of the ‘now’ while the world around it grows, decays and transforms. Unlike most artworks, which find new ways to relate to their socio-political and cultural surroundings, Factory of the Sun is forever a video about the year 2015.

_0-itok=2A25zDgY.jpg)

_0-itok=pCh8jsKk.jpg)

_0-itok=raBlzbmO.jpg)