The National: New Australian Art

The National: New Australian Art brings together three of Sydney’s major art institutions—the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) and Carriageworks—to present a major survey of contemporary art in three iterations over six years. This nationally-focused biannual survey offers an important counterpoint to the more internationally-focused Biennale of Sydney. The title is obviously provocative, invoking ideas of sovereignty, national identity, citizenship, myth-making/breaking, and settler-colonial history. The curatorial premise and the catalogue’s commissioned essays by Helen Hughes, Daniel Browning and Sunil Badami, together and in different ways set out a politics through which this provocation can be read. The National is also the anti-national, the pre-national, the post-national, and, of course, the lively, diverse sets of practices that articulate how to live in and against nationhood. And the work itself in many instances goes well beyond the provocation, speaking not just to the concept and problem of ‘Australia’ but also to complex intersections of global economy/vectors of power, transnational solidarity, diasporic politics, and radical epistemologies of past, present and future.

While the show isn’t explicitly organised around conceptual threads, a number of themes emerge in situ and across the three venues: decolonisation and the long process of unsettlement; an interrogation of the archive and its claims to history; and the deep materiality of mythology and narratology. Across these themes and in the show more generally (including its paratexts) is an emphatic discursivity—the show is rich in critical language(s). At Carriageworks, Agatha Gothe-Snape’s The Fatal Sure/The National Doubt (2016–2021) acts as a kind of terminal space or waiting room from which to consider the future via an engagement with the past. In this installation, a small section of the Carriageworks’ foyer is converted into a non-place (as per the anthropologist Marc Augé’s construction, a non-place is a space of transience or impermanence, like an airport lounge or hotel lobby) with institution-blue carpet, mirrored walls and a single lounge seat. On a flat screen plays a video that moves from block colours to a blurred pastel gradient to text. The text, echoed in an audio track that inhabits the non-place, is derived from Robert Hughes’s documentary The Shock of the New, a work that considers the role of art in the mediation of history. In the audio, Gothe-Snape recites from memory key lines from Hughes—her voice stops and starts, snagging on a word or failing to move on from a forgotten cue. In the stop and start, a space opens in which we might ask again the question of how we deal with history and how we approach work that seeks to break history apart.

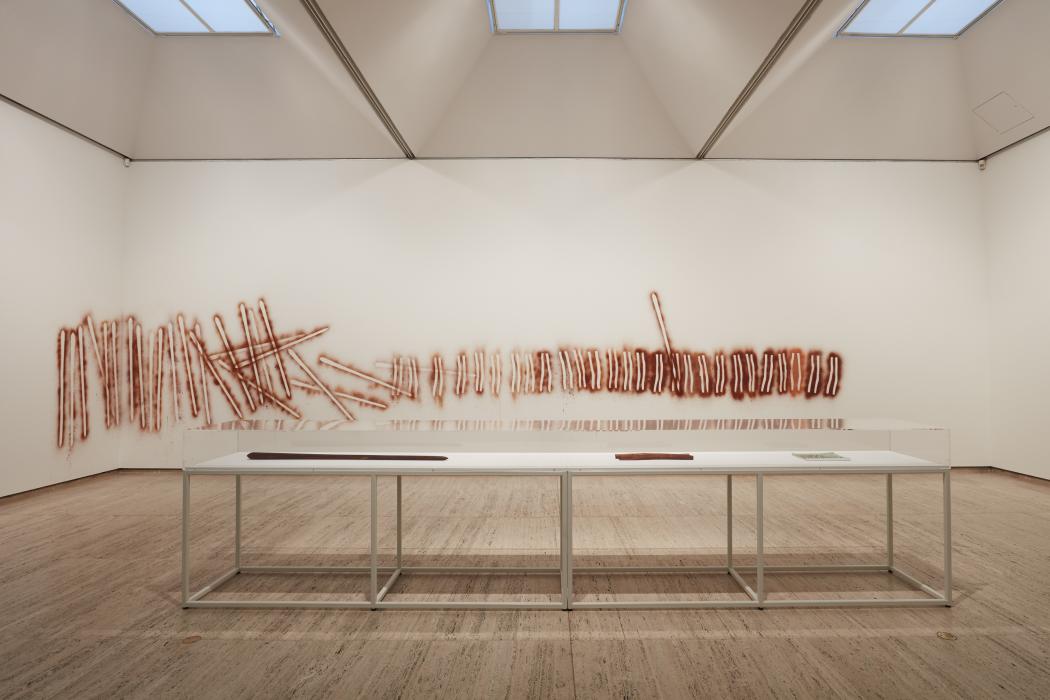

At the AGNSW, Dale Harding engages with family, local and national histories and their traces in a standout work. Know them in correct judgement (2017), made with the help of his uncle Milton and cousin Will comprises a long glass cabinet containing two small and one large fighting sticks and a book documenting an oral history (all of which reflect ongoing research into his family’s history) and a series of mouth-blown ochre and charcoal wall paintings. The largest painting shows relief forms of the fighting sticks used in social rites by Harding’s great-great-grandmother and her son on the Woorabinda Mission on Ghungalu Land. Another smaller painting is a redaction of the names of the missionaries, a gesture of both reclamation and disavowal. The work fully inhabits the space in which it is installed—the combination of porous pigment and definite edges, as well as the spread of objects and images across three walls of a long, open-ended room, coheres as a refutation of settler-colonial history and call for the continuation of culture and history as daily life, resistance and survival.

Helen Johnson’s The hills of hate (2017), Empire play (2016) and Or else (2016) at the AGNSW and Gary Carsley’s installation at the MCA (comprising a number of works) approach the (de)colonial through a reconstruction of the archive that challenges the enduring fantasy of the European origin myth. Johnson’s paintings compress historical time into flattened planes in which colonial and contemporary moments overlap. These layered scenes restage narratives of nation and citizenship (ships, cops, maps, bodies governed and governing), the irreconcilable temporalities showing the continuation and continuing catastrophe of such narratives. Carsley’s installation brings together video works in which a digitally-rendered bust of Cicero is made to ventriloquise (via Carsley’s own mouth) Gough Whitlam’s optimistic campaign speech at Blacktown Civic Centre in 1972 on a backdrop of wallpaper that moves between ornate, floral patterns and semi-glitchy digital pastorals. These digital pastoral scenes, transferred onto IKEA chairs and the infinitely reproducible surface of the gallery wall speak to the perverse, generic desire to remake home in the colonial outpost, always at once fantasy and scene of horror.

Other standout works include Gunybi Ganambarr’s Gapu (2017) and Milnurr (2015), which feature inscription on rubber and galvanised steel respectively. These two works, part of a larger sculptural installation at the AGNSW, speak to the politics of native title and claims to land in the context of the increasing embeddedness of sovereign powers and major corporations. Sharing the same space is Megan Cope’s RE FORMATION part 3 (Dubbagullee) (2017), a large-scale midden made from hand-cast concrete Sydney rock oysters and copper slag. Cope’s reclamation of the midden as an architectural practice is an assertion of the complexity of Indigenous knowledge and culture and a rejoinder to the destruction of middens by Europeans in order to extract lime for mortar. Over at Carriageworks, Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran’s installation fills a room of its own, collecting several sculptures (a giant earthenware tower is the centrepiece) and wall paintings laced with neon. There’s a mix of the electric, erotic, totemic, iconic and fetishistic, brought together in a work that feels at once excessive and unfinished, in the best possible senses of both words. Nithiyendran’s work is a performative declaration of identity and the cultural histories that cohere (or not) as such, mapping out a space in which queerness and Tamilness modulate and amplify each other.

The exhibition was at its strongest at Carriageworks and the AGNSW, where the shows felt both cohesive in their own right and very much resonant with the broader aims of the project. At the MCA, the works made less sense in relation to each other in the space and to the provocation of the ‘nation’. Despite the slight asymmetry across the three venues, The National is a genuinely exciting show, staking a claim for a different future.

-itok=4mDs9ajD.jpg)

-itok=JOjIAQTt.jpg)