Landscapes Away from Landscapes

To get to the Rodd, you have to drive through confined English country lanes that are hedged on both sides. Locals and alternatingly holidaying and then hungover British couples barrel down the lanes’ narrow turns. I, and the other interlopers in hire cars, warily edge along, clinging to the hedge row. Above the hedges, are crisp green fields beneath ruminating cows; fulgent yellow squares, rectangles, and rhombuses of flowering rapeseed; cottages shyly peaking around wooden gates; and manors resting atop hills with Koonsian BMWs parked outside or in repurposed stables. As I am driving slowly, these landscapes do not blur into a rapidly unravelling reel of colour, but smoothly replace one another in a procession. Apart from the cars, little would look remiss in English landscape paintings—say by John Constable. Amidst such landscaped environments, half a mile from the Welsh border and a three-and-a-half-hour drive from London, lies the Rodd. The home (built in the 1590s), with a twentieth-century grain yard, cottage, studio, and seventeenth century tithe barn acting as the Gallery, was Sidney Nolan’s home from 1983 to his death in 1992. It is now the site of his Trust. The view of the Hindwell Valley from where I parked at the back of the property was what convinced Nolan to buy the Rodd. The gentle hills, coppiced woods, and farmland where drought seems impossible—all in all, a checked and reassuring landscape—was what he looked out on each morning. What is strange is not so much that none of these landscapes found their way into any of the fifteen paintings Nolan made at the Rodd that form this exhibition, or any of Nolan’s paintings during his decades in England. Nor is it strange that the site of his legacy (a legacy built and existent in London and Australia) is located on the Welsh border. What is strange is the dislocation of the landscapes he worked in, from those he painted, those he is now remembered in, and those the trust perpetuates his legacy in.

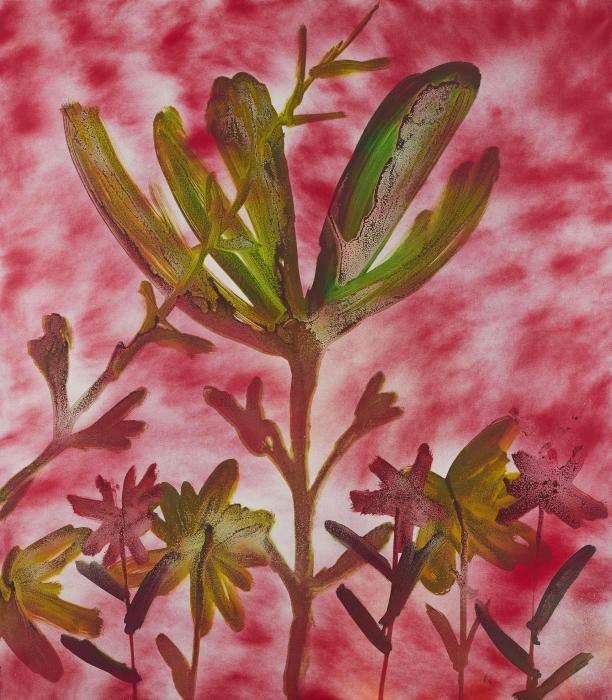

On my way to the gallery, I walked past a gardener weeding a flowerbed. He gently cupped luminous flowers with one hand as he pulled any weeds from the flowers’ midst with the other. Inside the gallery, two radioactive, blistered enamel spray paints of flowers dominate the right-hand side of the barn. Nolan always liked quick-drying paints, partly for the challenge and partly for the result. He described painting with polyvinyl acetate was ‘like cooking a soufflé. There was a point at which it bubbled and hardened and you couldn’t use it anymore; it was like lava.’[1] The spray paints he used during his time at the Rodd are not so much a shift in materials, but a shift in time—an acceleration. The paint has been applied and dried so quickly that the flowers appear diseased. Their emaciated, pustuled stems can barely hold up the flat fronds. And yet one feels impelled to step and look closer, as the congealed bubbles of paint resemble cells under a microscope. These cells, however, seem permanently trapped in the anaphase.

Nothing of the English flowers outside is present in these undefinable plants. [2] Nor is there any sign of the care or patience of the gardener. Nolan is hasty, abrupt even. There is a rapacious ferocity in these and other late creations by Nolan that seems to tear at the forms of the paintings and the very material itself. Theodore Adorno, the most prominent proponent of ‘late style’, regards such ravages as a kind of release from the delusion of formal and subjective mastery over art. The result being that ‘No longer does he [the artist] gather the landscape, deserted now, and alienated, into an image.’ [3] Instead, the artist lights the work with ‘the fire of extremes’, which, Adorno writes, ‘breaks out and throws itself against the walls of the work, true to the idea of its dynamism.’ Nolan’s tearing vigour cannot be found in any of the gentle tending and caring for the surrounding landscapes. Indeed, the trust conserves, even tames, this energy. All museums restrain the artworks within them. But the continual preservation of the wood, the gradual multi-year transition of the farm into an organic farm, and the cyclical tending of the house gardens work like a genteel inertia against Nolan’s dynamism.

More glaringly ‘out of place’ were the paintings in the African and Antarctic series from Nolan’s travels in 1962 and 1964 respectively. The two elephant paintings are actually portraits, not landscapes. The elephants do not lumber horizontally, but climb ponderously up the vertical plane. At first glance they do not appear to be elephants, but hung offal—pink, bloody, still palpitating. Shrubs dot the background like a child scrawling on wallpaper. On the opposite wall is Spitzbergen, painted from memory in 1984, several years after the original Antarctic series was completed. Here, in the swept atmosphere that is more of an abyss, with an abandoned, unidentifiable structure in the grinning maw of a lake encircled by sooty peaks, is the quintessential Nolan landscape. These have often been described as alien, violent, harsh, awe-full and awful, brutally void, and isolating. [4] If, as Kenneth Clarke (the deus ex machina who hoisted Nolan onto the world stage) wrote in Landscape into Art, ‘We are surrounded with things we have not made and which have a life somehow different from our own,’ then Nolan paints such difference as violently indifferent. Nolan not only paints from a distance, but places the viewer at a distance rendering the landscapes vertiginous, endless, and insuperable.

‘It is incredible to imagine,’ writes, Kate McMillan in an article on Nolan and the colonial sublime that the most iconic of Nolan’s images were painted from the amenable surroundings of British life—utterly bereft of the harshness of outback Australia’ and the innumerable other places to which he travelled. [5] On the one hand it is very easy to imagine. Nolan took photos as he travelled, and paint charts show his meticulous mixing of colours in the studio. (The blue of the lake in Spitzbergen is, for example, ‘#058 Peris Blue’.) That many of the exhibitions fifteen paintings are the sunken-eyed portraits that Nolan seemed to churn out with almost Sisyphean regularity reveal that he can work almost anywhere. But on the other, if the exhibition showed, or rather, intended to show how Nolan worked at the Rodd—one can wander through the house and peer into his still preserved studio (which includes an enigmatic, upright, unused piano)—it instead exposed the difficulty of preserving an artist’s legacy in a locale when Nolan himself worked from a distance. Or, more precisely, when Nolan refused to be cabined by a landscape, cribbed by a place, fixing his legacy here is like collapsing a map into a point. Barry Pierce asks, ‘Ultimately, how precisely can we define Nolan’s place and identity between where he was born and the myriad of places on the planet he stayed and visited; between the new world and the old; between the power of thought and the seduction of the seen?’ The answer is that we cannot define Nolan’s place, but only see Nolan’s places—mythical and abstract, broken and free, and never to be located.

[1] Sidney Nolan interviewed by Colin MacInnes 4 July 1957. Quoted. in Jo Crook and Tom Learner, ‘The Impact of Modern Paints,’ (London: Tate Gallery, 2000): 24.

[2] The Catalogue and Curator do not know what species of flora these plants even abstractly resemble.

[3] Theodor Adorno, ‘Late Style in Beethoven,’ in Essays on Music, ed. by Richard Leppert, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 200) 567.

[4] See, for example, John Cornall, ‘Landscape and Light: Sidney Nolan and Recent Australian Art,’ London Magazine, vol. 37, 1997 47–55.

[5] ‘Sidney Nolan and the Colonial Sublime,’ in Transferences: Sidney Nolan in Britain, ed. by Rebecca Daniels (Chichester, Pallant House Gallery: 2017), 61.

%20copy-itok=ISSspwa0.jpg)

%20copy-itok=Razw9l4K.jpg)

%20copy-itok=IBJwm7dl.jpg)