Infrastructuralism

The criminally underrated TV series Better off Ted (2009-2010) satirised the activities of twenty-first century corporate business, through the fictional company Veridian Dynamics. The show played on the bureaucratic language (also known as ‘bureaucratese’ or ‘weasel words’) used in business: obscure jargon, characterised by wordiness, euphemisms and clichés, that is designed to complicate simple ideas, deflect responsibility and preserve power dynamics. The same can be said of ‘art speak’, defined by Alix Rule and David Levine as ‘International Art English’, the language commonly seen in contemporary art press releases, catalogue essays and artist statements, and often using made up terms. [1] Infrastructuralism, one such jargon term, takes as its root the word ‘infrastructure’—which refers to both physical site and institutional structures—and elevates it into the realm of an art movement with the suffix –ism.

The La Trobe Art Institute (LAI) is, by its very name and its relationship to La Trobe University, an institution. It functions within bureaucratic systems, which are reflected in the physical infrastructure of the building. It is in this context that the five artists in Infrastructuralism respond to the systems and structures within which their works are presented—a form of art making referred to as ‘institutional critique’. In a move that could be interpreted as the artists ‘hacking’ the LAI, the exhibition expands beyond the two formal gallery spaces, infiltrating the foyer, reception, auditorium, hallways and stairwell of this institutionalised space.

Agatha Gothe-Snape’s work EVERY DECISION AN ARTWORK, EVERY ARTWORK A DECISION (2018) offers a framework for the exhibition. The artwork title acts as an ambiguous proposition, repeated throughout the institution’s physical space and infiltrating its daily operations. A printed email from LAI’s Senior Curator to the Curator, unassumingly pinned to the wall of the gallery, reveals that the phrase is to appear in both of their email signatures and be used as their phone greeting throughout the duration of the exhibition. And if you are observant, you will see the phrase on the front windows of the building, quietly setting the scene for the exhibition before you enter.

Upon entering the gallery space, you encounter a small freestanding wall with a coffee stand in the style of an office kitchenette—complete with bar fridge, urn, paper cups, and jars containing instant coffee and sugar sachets—referencing the culture of office hospitality that is usually hidden behind closed doors. Shannon Lyons’ Instant Gratification (2018) is indeed a working coffee station, and visitors are welcome to make themselves a beverage. But walk around the back of the stand and you will see that the wall is a temporary structure, held up by wooden struts. The framework and construction of the work is deliberately made visible. It reminds me of the fantastic exhibition The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied. (2017) at Fondazione Prada, Venice, which presented video works by Alexander Kluge and photographs by Thomas Demand within multiple sets by stage and costume designer Anna Viebrock in the 18th century palazzo of Ca’ Corner della Regina. The practice of revealing the behind-the-scenes techniques and processes allows the audience an insight into the practicalities of art making and removes some of the mystique that renders high art ‘untouchable’. An amusing layer is added to Lyons’ work because in the LAI foyer there is a trestle table laid out with the makings of tea and coffee, perhaps in preparation for a community morning tea. One is left wondering whether this is also art, or if it is a parallel non-art activity hosted by the institution.

The rest of the gallery space appears to be a mostly empty white cube—except for an unplugged portable speaker with long microphone cord, sitting on a small trolley in the space, as though in preparation for an event. The speaker and microphone function as props or placeholders for Helen Grogan’s performance work CONCRETE ROOM (2001-2018), which will be activated on the final day of the exhibition. A performer will trace the outline of the room with the microphone, the cord and speaker following throughout the space, to generate sounds, thus creating an audio map of the space. In doing so, Grogan utilises the physical infrastructure of the gallery as both instrument and sheet music. But until then, the speaker and microphone sit patiently, in anticipation of activation.

Carolyn Eskdale, who has long been fascinated with interior spaces and rooms, spent time in the gallery prior to the exhibition, mapping and documenting the physical space. The outcome is Mediation photoworks (2018), a series of square photographs installed throughout the institution—in the gallery spaces but also, the hallways, the auditorium, the foyer and the stairwell. Each photograph highlights a corner, angle or space that would normally be overlooked, and is displayed at the perspective from where the photo was taken, thus presenting a mirror or copy of the space, and provoking a double take. There are no people visible in the photographs (and as far as we can see, no art), but the artist’s presence is implied through the cardboard boxes that are stacked in different formations in each scene. The boxes themselves, utilitarian items, hint at backstage gallery operations involving the installation or de-installation period of an exhibition, which takes place behind closed doors and out of sight of visitors.

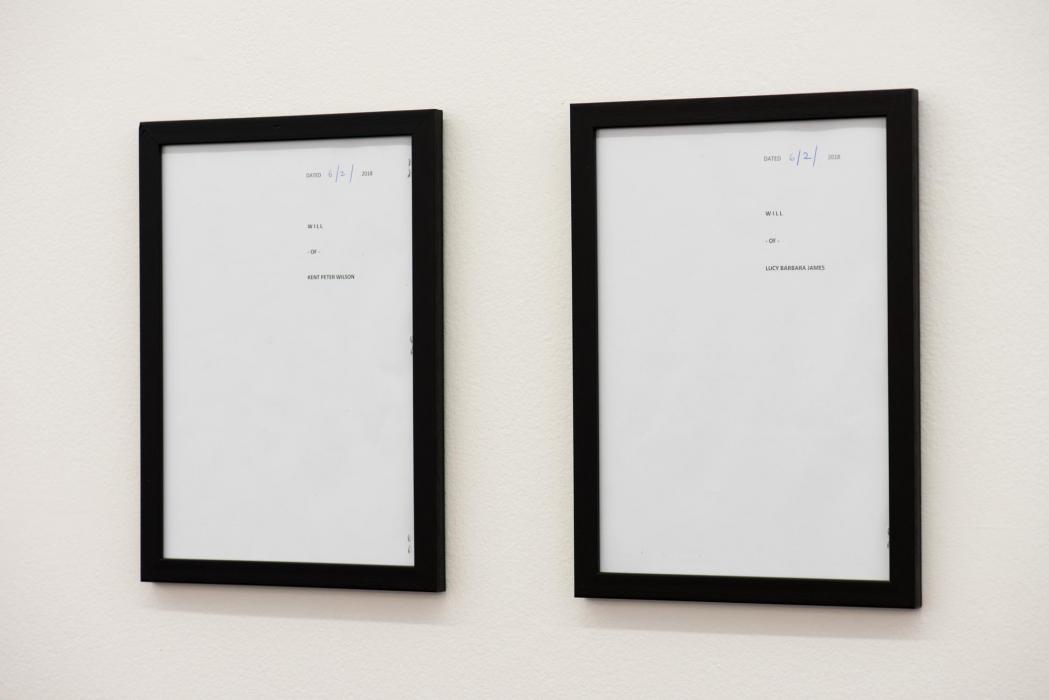

On a gallery wall hangs two modest, A4 sized frames. Each holds a document dated 6/2/2018. One states ‘Will of Kent Peter Wilson’, and the other ‘Will of Lucy Barbara James’. It is not until referring to the catalogue details of Jessie Bullivant’s work The Guardian (2018) that the meaning is illuminated: “two wills authorising the artist as guardian to the youngest child of the Senior Curator, in the event that her parents die before she attains adulthood”. The work interrogates the usually hidden relationship between artist and curator, and the primary role of the curator as ‘carer’ of the art: the artist’s baby, if you will.

It is unusual for a curator to appear so visibly in the exhibition, but in Infrastructuralism, the backstage operations of the gallery, its staff and external programming, are placed centre stage. The institution and its staff are clearly embracing the novelty of such a play with convention. Even the exhibition brochure (featuring a clever text in the form of a glossary of terms by Sophia Cai) reveals the usually hidden elements of document design and formatting, with the colour grading, file name and document details shown to the reader.

I am told that many visitors have been confused by the apparently empty spaces, assuming that the gallery is closed for a function or in-between exhibitions. This misreading is understandable given the artists’ use of utilitarian objects as art. In The Square (2017)—winner of the 2017 Cannes Palme d’Or—Christian, the curator of the fictional X-Royal museum, is interviewed by a journalist who presses him about the ‘art speak’ used on the institution’s website. In an attempt to explain the unexplainable, Christian eventually poses the question: "If you place an object in a museum...for instance, if we took your bag and placed it here, would that make it art?" The Duchampian assumption that any non-art object intentionally placed into the context of a gallery or museum can be elevated to the status of art relies on the designation applied by the artist and the structures of the art institution. [2] As critic Brian O’Doherty explained in his important text ‘Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space’ (originally published in Art Forum in 1976), the white cube is not a neutral space, as we were led to believe, but frames an object within the context of the institution, elevating it to the status of art. [3]

Attached unassumingly to the wall in the LAI hallway is Shannon Lyons’ final masterful contribution: an orange sign with the word ‘COFFEE’ and an arrow pointing towards her coffee cart. It is easily missed—I only just spotted the sign on my way out—due to its use of the same font and colour orange as LAI’s institutional signage (and, I’m told, it was produced by the same company), which camouflages it within the institutional context. This, like the other works in Infrastructuralism, encourages us to pause and look a little closer at both the visible and invisible structures within which we operate.

[1] Alix Rule and David Levine, ‘International Art English’, Triple Canopy, issue 16, July 30, 2012, https://www.canopycanopycanopy.com/issues/16/contents/international_art_....

[2] Duchampian is a perfect example of an International Art English term. It refers to Marcel Duchamp’s ‘readymades’ – utilitarian objects which the artist placed in the gallery as a way of questioning the value of art.

[3] Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, University of California Press: Berkeley, Los Angeles, London; 1999