I, Us, Them: A dark triad, radiating out from a centre and closing in

‘This has come to me in pieces, but I shall attempt to collate it into a whole. Let’s start at the beginning. In the beginning god created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep.’ [1]

—Jo Randerson

As if knowingly, a friend recently sent me a link to Jo Randerson’s profound and funny contribution as part of the 2006 project Are Angels Ok?: An extraordinary date between eminent New Zealand writers and physicists. With her introduction accompanied by the gentle cue of an angelic hymn and staged as a series of choreographed interruptions—‘oh, I’m sorry, further information just at hand’, as if live news flashes that inform us of an up-to-the-minute take on how life on earth began—Randerson takes us into her web of darkly sincere satire on relationships and the universe. [2] Randerson’s 39-minute presentation is the result of her participation in a series of ten collaborations between New Zealand writers and scientists, in which she specifically focuses on quantum physics and the necessity for all life forms to coexist. Her presentation weaves in and out of worldviews—Christianity, Daoism and Pākehā and Māori relations—as well as hypotheses from the field of quantum physics and a striking metaphor about how dark matter can be used to describe the way some artists kind of fall away from the normal atoms to bring the world necessarily difficult content. To heavily redact Randerson’s overall project—in line with her wry presentation tactics, which feed into an effective tautological telling and re-telling of the story of life on earth—she begins: there was an exploding cosmic egg and a pretty big bang which is constantly moving outwards, getting bigger and bigger until one day it will reveal itself as ‘a kind of loud bang or whimper’ at which point everything will be moving inwards and might again reveal itself as an exploding cosmic egg, or something. [3] The cyclical nature of which she introduces in a tongue-in-cheek way as being ‘rather boring’.[4]

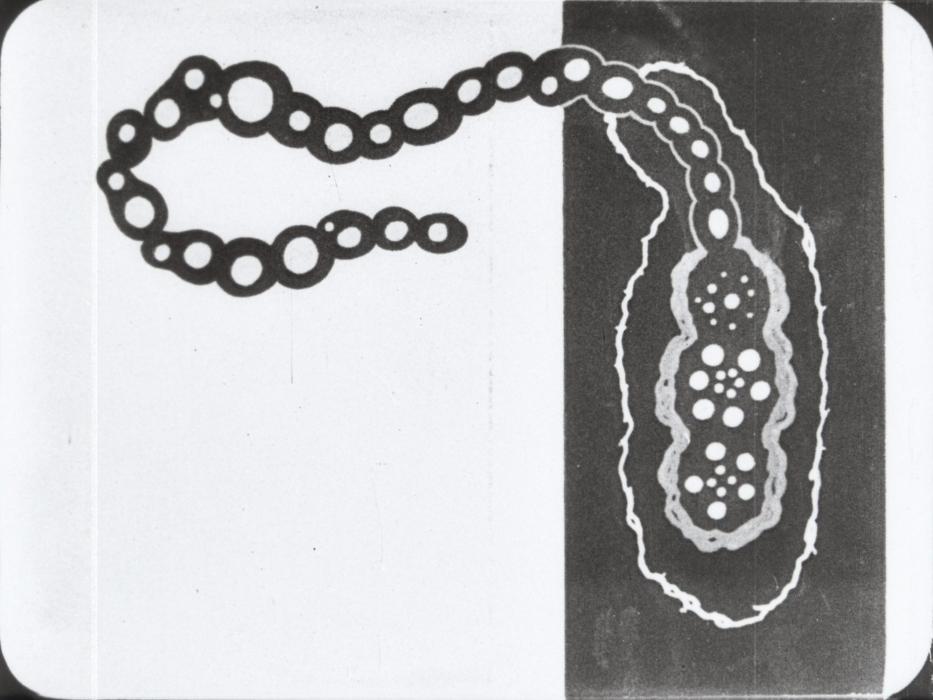

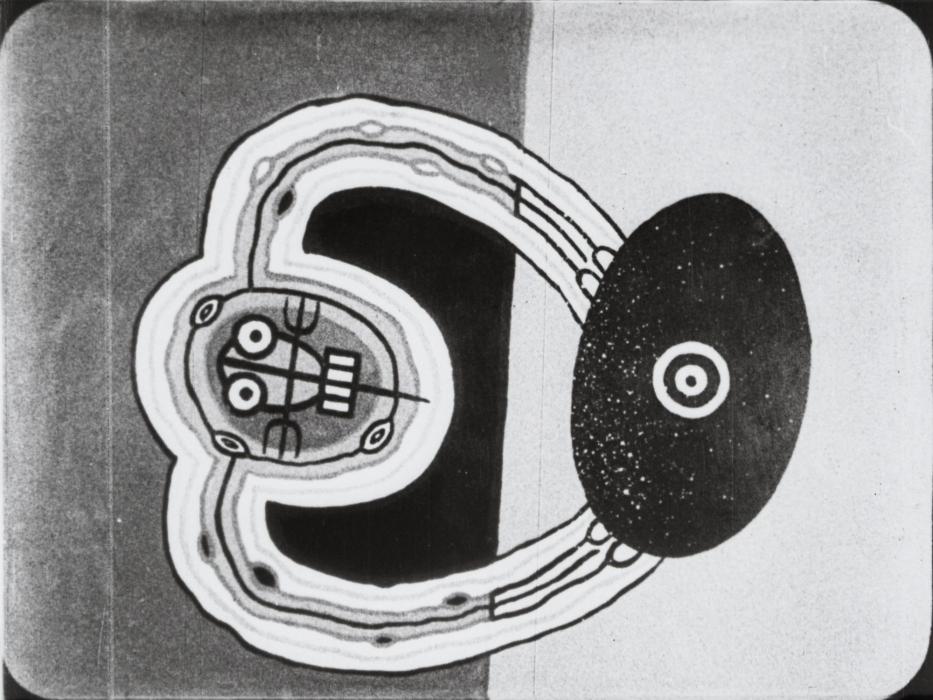

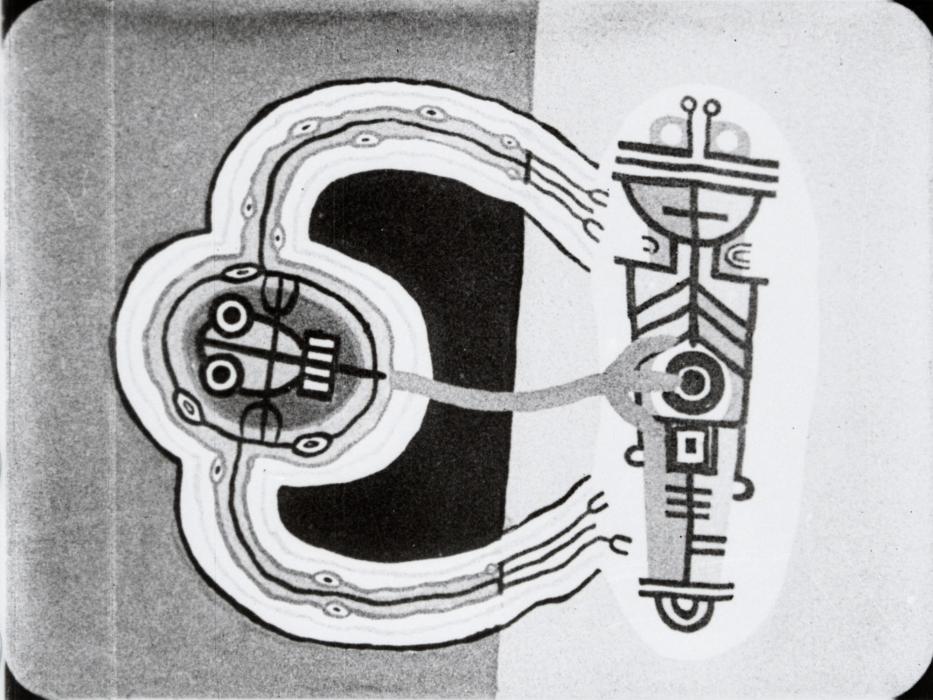

As I’m listening to Randerson’s protracted imaginary, Len Lye’s earliest cel-animation Tusalava is replaying in my mind as its visual score. Randerson’s deliberately verbose and yet vague descriptions of the cycles of life and entropy on earth are strikingly similar to the way that Jamie Sexton earnestly describes Tusalava in an overview of the film for BFI Screen Online:

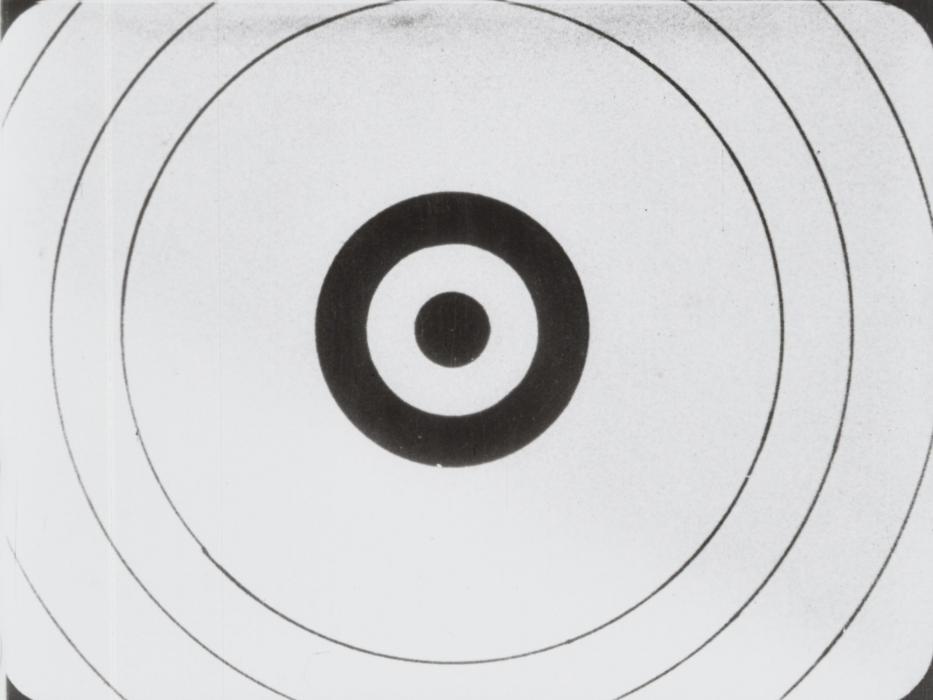

The film begins with the screen divided into three rectangles, with a series of dots and circles wriggling and twisting. Eventually collapsing into two rectangles, the wriggling shapes continue to mutate and create intricate patterns. Out of one of the rectangles a totem figure eventually appears and is invaded by a wriggling shape, creating a frenzied motion. Eventually the shape is blown out of the screen, replaced by a number of spirals, which are engulfed by a black dot. [5]

Through Randerson’s account of life on earth, she paints the writer’s picture of what Lye’s film was inherently getting at almost a century ago. The notions that innumerable contradictions and disjunctures exist within any one thing, or that somehow we can control the agency of the things we create (as in procreation but also creative works of art), is central to the evolutionary narratives of both Randerson’s and Lye’s meditations. It is a concern most obviously captured at the moment that the two organisms in Tusalava—after having evolved out of one unified chain of larval sequencing—turn on each other and fight for supremacy. It is regrettable to acknowledge that this film is still so relevant today—for reasons other than Lye’s general ongoing legacy—where colonial struggles endure.

Common historic accounts by Sexton and others point to Lye’s film being rejected by audiences after its screening at the London Film Society in December 1929 for being too non-literal against the more reasoned, geometric abstractions of the time. [6] But a contemporary reading of the film’s so-called difficult incorporation of organic shapes—out of which audiences apparently struggled to find literal meaning—is quite feasibly a convenient excuse for what is an obvious, and widely held genuine integration, of South Pacific and Aboriginal Indigenous imagery. [7] In other words, it is apparent that historically at least Tusalava presented an array of broader epistemic, rather than merely formal challenges.

In many ways, Randerson’s presentation cast an ontological filter over the connections I was making between Lye’s film (on display as part of Tūrangawaewae: Art and New Zealand, works from the collection at the Te Papa Museum in Wellington) and two other discrete exhibitions: Tony de Latour’s survey exhibition Us v Them at the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu and Sam Clague’s exhibition Taste Nature at the Ilam School of Fine Art Gallery, University of Canterbury, also in Christchurch. Randerson’s illuminations are an interesting prompt for thinking through art’s role when it comes to the creation and efficacy of uneasy or difficult content, particularly in light of the historic amnesias and denials that we seem to be confronting in our current political climate.

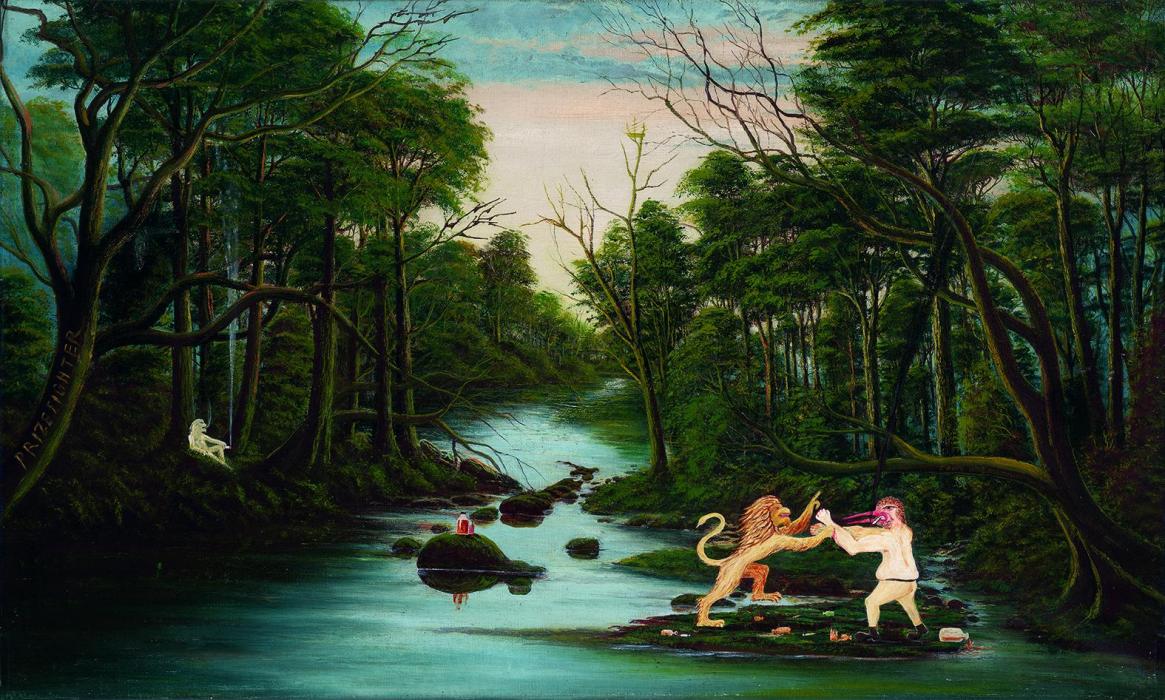

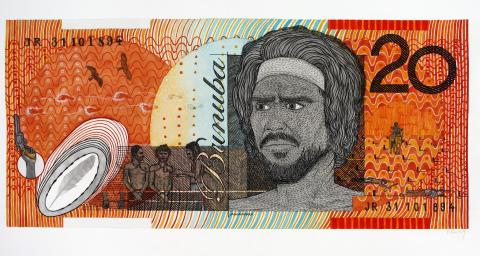

While the works across these shows are divergent in their formalisations and conditions of production and reception, they are each challenging particular ideologies in the form of capitalism, colonialism, classism and warfare et al. Without making too apparent a moralistic claim over what are largely aesthetic projects, works such as de Latour’s Revisionist series stage their presence in a spirit of agreement with the kinds of reclamations taking place against global fascist and neoliberal status quos. In this series of works made between 1999 and 2009, de Latour takes existing works of art—such as the fine china and ornately framed, often kitsch colonial landscape paintings that form part of his extensive collection of antique regalia and memorabilia—reworking his punkish and dystopic iconography into their congenial lacunae. While de Latour is clearly into occupying and defacing the largely empty scenes of these images and objects, it is interesting to note that he retains the original artist’s signature (where present) and in many cases is not compelled to insert his own. He is roughing them up, but he wants their former presence to be known. This gets to a lot of what his art is about: making visible the uneasy relationships between people and their environments.

‘Who moves around what? [...] When we study the world around us, we must look not only at individuals, but also the environments in which they are placed. A relationship can be revolutionary, it can sometimes lead to death threats’—Randerson. [8]

In her catalogue text for Us v Them, Lara Strongman describes de Latour’s earlier works as functioning in the following way:

‘Any illusion of the nobility of, or putative redemption for, the colonial enterprise was erased by de Latour’s depiction of Aotearoa’s European settlers as disorderly, degenerate vandals: beer-swilling barbarians in a lethal paradise.’ [9]

The project that Strongman describes is apparent in works like Prizefighter (1999). A central work from the Revisionist series, it is a medium sized painting depicting a brooding, vacant river passage which de Latour populates with his bastardised coat of arms: a brawling lion and kiwi bird. Imperialism and provincialism fight it out, while on the banks behind them is a grey, apathetic-looking long-haired figure (perhaps another lion), less heraldic, casually smoking, gaze averted.

With the same charge of intent that de Latour uses to splay his endless recycling of images such as the lion and the kiwi, there exists criticism against his use of ‘fascist type’ comic heroes (notably in a letter from the then editor of Harper’s Bazaar, Louis Leroy, in response to Giovanni Intra’s proposed coverage of de Latour’s 1994 exhibition Bad White Art). [10] While it is apparent that the assumed lackadaisical nature of de Latour’s earlier ‘pencil-case’ style paintings are getting at a general dissensus of authoritarian strictures—through the abject portrayal of national and colonial icons—Hal Foster’s question, put forth in Bad New Days, is an appropriate one to ask here: “is the abject [...] disruptive of subjective and social orders or foundational of them, a crisis in these orders or a confirmation of them? [...] an exceeding that is also a reaffirming?” [11]

This question might be appropriately asked of both de Latour and Clague, for whom debasement and vandalism are beloved terms of endearment (sanctified as they are, despite the artists’ outright efforts and successes to pervert and destroy cherished cultural artefacts, national icons and neoliberal freedoms). For both artists, their works do this against an at-times brittle and decomposing backdrop of avant-garde and post-punk demise. This is even more apparent in light of a lot of the punk and DIY culture that Christchurch is known for having been wiped out in the 2010-11 earthquakes, along with the fact that both artists were either born, raised or studied in Christchurch.

In Taste Nature, Dunedin-based Clague has created a series of works that resemble what we might think of as algorithmic degenerations of organic and computational twenty-first century desire. Clague’s central Untitled Installation of 2017-18 reads as the failed outcome of a student’s attempt to restage The Way Things Go, the famous kinetic sculpture by Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss. The ephemeral looking installation—which is made up of an abeyance of otherwise functional computer devices and electronic cords, chain-links and slumped moving blankets of the kind synonymous with art installers (of whom Clague is one)—stand in as a central axiom for what I see to be the primary success of this show: to reveal, through a kind of poised squalor of anti-aesthetics, the dark side of our compulsive, consumptive practices. In other words, Clague (whether he means to or not) is sparking a conversation about what the other side of comfortable privilege looks like. He is bathing in the decomposition of other people’s hard labour that is most often, conveniently, hidden from our view. In the exhibition catalogue, Clague’s creative process is summed up by Chloe Geoghagan as such: ‘amalgamated materials are aerated and turned like organic fertiliser over time to generate new forms representing a failed system.’ [12] Untitled Installation cuts through the modest art school gallery space like a stubborn and defiant trajectory.

On the far wall of the gallery is the triptych Don’t look at the carpet, I drew something awful on it (2018), an equally bloated and deflated depiction of the interior life of one’s bathroom or kitchen. These works, along with the show in full, reveal the debauched realities of consumables in arrears: banana skins, recycled paint, polystyrene, coffee grounds, nicotine gum, dirt and plaster et al. These carpet paintings function like modern-day mirrors to the atavistic primordial soup that science (and Randerson) tell us the earth was born out of. And while these paintings are meant to be ugly—the play on the word taste is certainly a visceral one in the presence of these works—there is a kind of accumulative presence that evokes a doleful beauty, much like the vibrations that are plucked out of an Anselm Kiefer work that cannot be anticipated by its reproduction alone. Taste Nature brings us to the edge of a kind of ontological shift that Randerson and Geoghegan speak of: a steady crescendo that Lye’s film and de Latour’s exhibition both seem to close in on at the exact point of destruction (in the former), and creative transformation at the bridging point of a move from figuration into geometric abstraction (in the later).

Through a specific set of stylistic elisions, Taste Nature confronts one of the greatest ethical challenges of our time: the gathering speed of the visible signs of the Anthropocene, where we are fast running out of hiding space. Clague’s works are elisions in the true sense of the word: as aporia, an irresolvable internal contradiction that gets to the heart of what it means to both reject and join forces with our turbid desires. Perhaps it’s something like the poet Anne Waldman describes when she takes on the dark spirit of Richard Nixon during a fire puja ceremony: in order to generate more compassion for the world we have to let in the negative energies as well as the positive. [13]

While this has come to me in pieces (mostly as pages and pages of spin-offs of what Randerson and others have projected), I too have attempted to collate it into a whole. The irony of the task at hand is that most of this material gets positioned below the end line of this document, and left out, hanging in the primordial soup of what I couldn’t quite articulate within the allotted word count (safe to say I struggle to write short form). Through processes of accumulation (creation) and eradication (an apt word for editing), creative works have something very fundamental in common with science: something about the cosmic egg bursting and the universe getting bigger and bigger until it gets smaller and smaller, as it waits for another cosmic egg. Pretty much.

[1] Jo Randerson, ‘Everything We Know', Are Angels Ok?: An extraordinary date between eminent New Zealand writers and physicists, Radio New Zealand, 1 January 2006, https://www.radionz.co.nz/national/programmes/areangelsok/audio/2491687/1-everything-we-know

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] Jamie Sexton, ‘Tusalava (1929)’, BFI Screen Online, accessed 9 July 2018, http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/442453/index.html

[6] Sexton makes a comparison between other experimental films—such as those by German painters and filmmakers Oskar Fischinger and Hans Richter—that were popular around the time that Lye first staged his cel-animation film Tusalava in London in 1929. While there are overt similarities between Tusalava and films such as Fischinger’s Spirals (c.1926) and Richter’s Rhythmus 21 (c.1921)—evidenced by the quotation of compositional and rhythmic strategies of black and white spirals and rectangles— it is apparent that Lye’s particular blend of modernist primitivism deviates from the more minimal geometric nature of these films.

[7] Lye’s particular approach to modernist primitivism is discussed at some length in the article ‘Len Lye’s Learning Curve’ by Roger Horrocks, a late assistant of Lye’s. In it, Horrocks discusses his views on Lye’s considerably more genuine anthropological approach to non-Western cultures, against the more famous examples of European modernist primitivism—such as Paul Gauguin and Pablo Picasso—who are considered to have reinforced, rather than critiqued colonial stereotypes through their work. Without wanting to extricate Lye as an exceptional Pãkehã (European New Zealand) artist, Horrocks’ synopsis is worth reading in light of his engagement with Australian Aboriginal and Pacific Islander cultures in particular.

Roger Horrocks, ‘Len Lyes Learning Curve’, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu Bulletin, vol. 189, 1 September 2017, https://christchurchartgallery.org.nz/bulletin/189/len-lyes-learning-curve#ftn-10

[8] Randerson, ibid.

[9] Lara Strongman, ‘Primitive Accumulations’, Tony de Latour: Us v Them, exhibition catalogue, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, 2018, p. 126.

[10] Giovanni Intra, Bad White Art: Tony de Latour exhibition catalogue, Tony de Latour: Us v Them, exhibition catalogue, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, 2018, p. 61.

[11] Hal Foster, 2017, Bad New Days, Verso Books, London, p. 16.

[12] Chloe Geoghegan, ‘It’s the end of the world as we know it’, Sam Clague: Taste Nature, exhibition catalogue, Illam Campus Gallery, School of Fine Arts, University of Canterbury, 2018.

[13] Anne Waldman, ‘Episode 55: Anne Waldman’, Commonplace: Conversations with Poets (and Other People), 11 July 2018 https://www.commonpodcast.com/home/2018/7/11/episode-55-anne-waldman