Heads Will Roll...?

In half-asleep Gymea, a suburb in Southern Sydney, an exploration of history was made manifest through parallel temporalities. The exhibition Rococolonial presented the excesses of the Rococo arts movement of Ancien Régime in France, and the colonial beginnings of the Commonwealth of Australia. Most of all, it attempted to show that what are perceived as disparate occurrences usually have threads of similarity, and that nothing, historically speaking, exists in isolation. Currently, any mention of Australia’s colonial past tends to elicit one of two responses—either it is discussed in the most censorious of terms, or it is swept under the carpet, regarded as too difficult for genial company. That this exhibition wanted to bypass both of these attitudes and adopt an open-minded, playful attitude to revisionist narratives shows perspicacity on the curator’s part. After all, one doesn’t usually think that while Marie Antoinette was tottering around in her tiny heeled shoes and enormous wigs, enjoying the last of her prestige, the landmass once considered terra nullius was being conquered for penal settlement. The exhibition statement baldly declared that it was attempting to do away with the categories that are so bent on dividing time into neat divisions, allowing spectators to ‘pass backwards and forwards between the slippery, stylistic classifications’ that are designated to both artworks and historical epochs.

The Rococo aesthetic was all about gilded frou frou, pleasing colours, an overabundance of curvaceous lines and decorative trimmings. It rejected the hierarchical approach that had until then dominated the arts, and that tendency was adhered to within RocoColonial. The works on display subscribed to a kitsch, spangled aesthetic. Using contemporary, common materials, they are collectively trying to evoke the forced gaiety that is so often shown in Rococo works—think of Watteau’s sad Pierrot in his 1718 painting, Gilles. Highlights of the exhibition included works by Sydney artist Justin Shoulder, whose electric light and silver-painted sculpture/performance art costume Lolo ex Machina (2015) worked wonderfully as a transcultural artefact dedicated to spectacle. His other work Caenus Cerabrallus (2007), facing out from the corner of the room, was a large dog lurking somewhere underneath showers of sparkling tinsel.

Australian mainstay Jenny Watson referenced Fragonard’s 1760 work Blind Man’s Bluff in her pair of faux-naïve linen works adorned with hastily applied acrylic, farmyard animal stickers and dollar store jewels. Blue Mountains based Peter Cooley’s ceramic birds were also attention grabbing—the gold topped cassowary most of all. In his hands clay remains wilfully rippled yet wonderfully contained. I immediately thought of an article seen via Facebook about a man killed by his pet cassowary, and how it needed to be re-homed: “hard pass on the death chicken” being one response. An example of cautionary beauty? Danie Mellor of the Mamu, Ngagen and Ngajan peoples, presented a photographic series called Fragments of Anthology (the allure of memory), (2016). The tinted cream and blue of the 19th Century photos was reminiscent of the willow pattern so often found on old tea wares, here featuring lush, fertile rainforest landscapes, occasionally interspersed with Indigenous inhabitants. One of the images showed a line of men waist deep standing in a river fishing. Collected together, the photos were an elegiac reminder of what has been irretrievably lost through the colonial project.

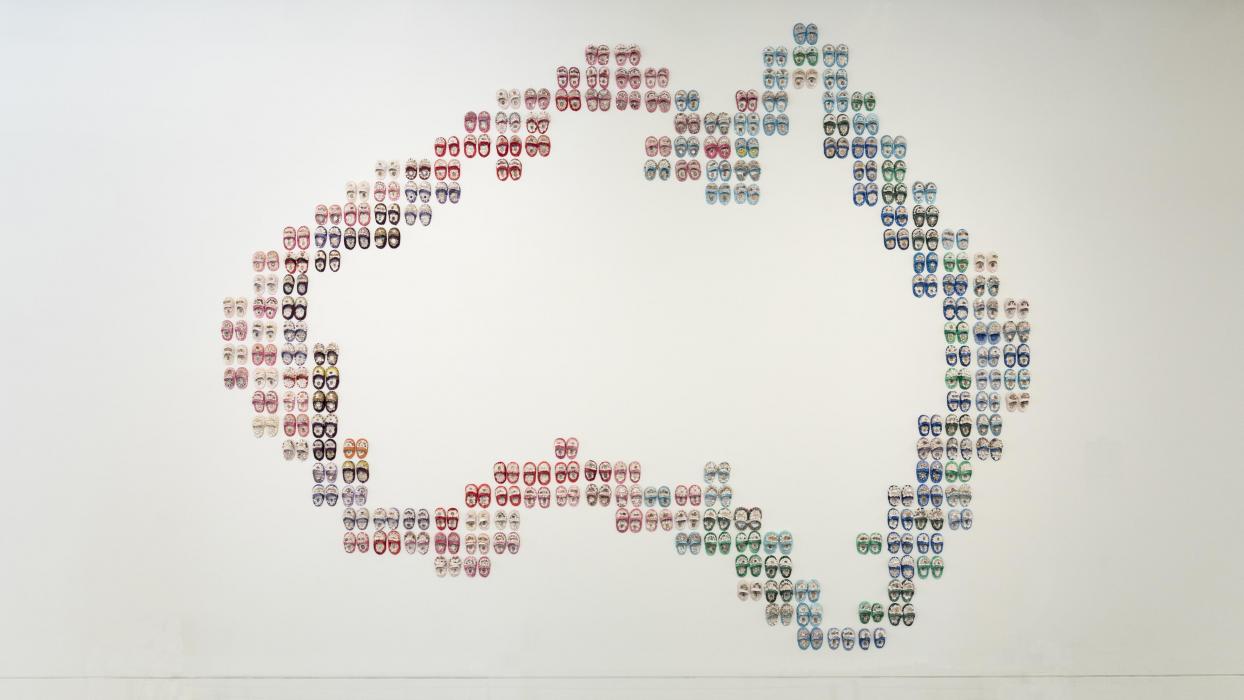

Bidjigal artist Esme Timberry’s large scale hanging installation took the rocaille motif and gave it a charged, local resonance. 200 pairs of childrens shoes were covered in glitter glue, lace and shells harvested from the NSW South Coast, together forming the shape of the Australian continent. But while the shoes suggest the coast line, Australia’s centre is simply the white wall. Behind the innocent façade, Shellworked Slippers (2008) alludes to children of the Stolen Generation; these state-mandated human rights abuses affected Timberry’s own family.

Nearly all who entered the gallery were instantly drawn to the large screen playing Joan Ross’s animation, BBQ this Sunday, BYO, (2011). Her now familiar, beautifully crafted animations explore the emergence of the nation of ‘Australia’. Ross uses a Joseph Lycett aquatint (a view of the Derwent River) as a template for the ensuring action. Her jerky figures shuffle about enacting the white man’s burden. Arriving on a magic carpet in lieu of a fleet, high vis wearing settlers interrupt a group of natives surrounding a campfire. Gradually, the insidious fluorescent yellow takes over the frame. An airborne, kaleidoscopic cluster of small pox cells finally ascends into the sky, exploding into fireworks.

In spite of these highlights, the exhibition lacked cohesion, requiring constant attention to the artist statements to understand what the works were about, why they were there. I tugged with the moral implications of the exhibition. Is there something questionable about making grim topics aesthetically palatable? When contemporary art explores pertinent themes, who ultimately benefits from it? Contemporary art is still largely a plaything of the well-to-do. I cannot help but sense, perhaps cynically, that art in this vein too often assuages white middle class guilt.

To use a decorative visual style for biting commentary only succeeds in fits and starts. The Rococo style was a temporary respite from Enlightenment thinking; that same Positivist brand of thought which valorises the scientific method and the advancement of technology is one the reasons why the Earth is now teetering on the edge of ecological collapse. The colonial is now the corporate; the machinations of empire have simply been given another guise. Perhaps the most fitting artwork of all was Belem Lett’s Paradise Lost (2016), which is suggestive of a dressing table mirror that offers no reflection. The broad oval frame is covered in glinting aluminium powder. The edges swarm with gaseous, sickly coloured clouds. It’s as if this false suggestion of a mirror is an indictment not only of the aristocrats and the colonizers, but of contemporary viewers too. Will those of the future look back on these times with admiration, or with moral opprobrium?

-itok=VUEfS0J6.jpg)

%202016-itok=0KqQbVkl.png)

-itok=ZV_WuuWH.jpg)