You Call it City — We Used to Live Here

By Tristen Harwood

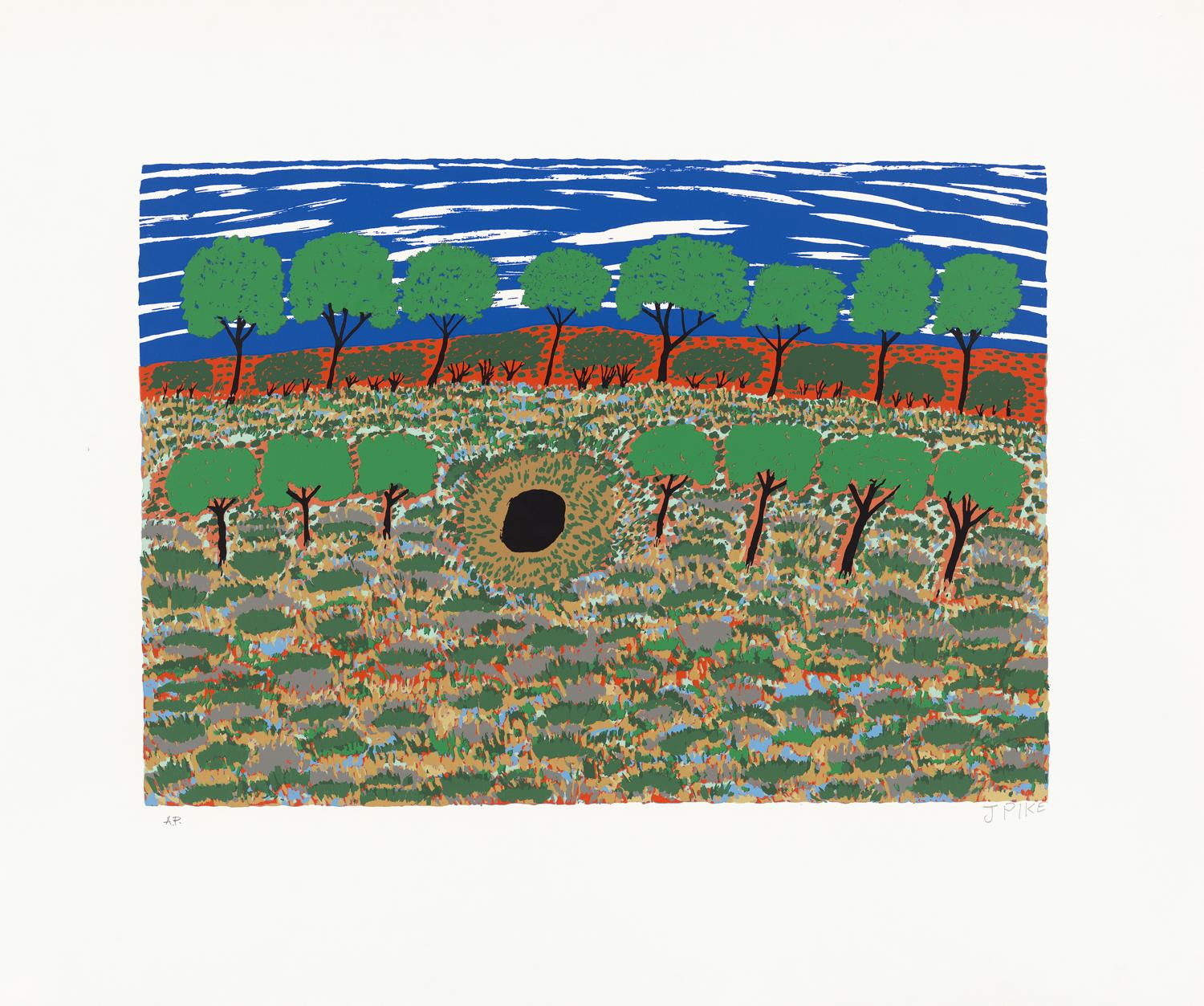

Jimmy Pike’s painting ‘Turtujarti kurrmalyi – A stand of turtujarti’ (1990) depicts the vivacious convergence of life in the desert. Two horizontal rows of turtujarti—black trees with oily green foliage—dart across the earth, which is flecked with green, blue, grey, gold, desert vegetation. Behind the trees, orange sandhills meet a cerulean sky dashed with white strips of cloud. It’s as though the scene is moving, glimpsed from the window of a rushing car, but by someone who knows the Country well. All the movement is grounded by a jila (waterhole) in the painting’s centre, a point of gravity where multiple narratives merge. [1]

The turtujarti tree is common in the Great Sandy Desert. It’s often found near waterholes, branches spiralling skyward, serried foliage capturing light. The tree has a vital role in desert life, providing shelter, marnta (edible sap), ngarlka (nuts), firewood and so on to humans along with shelter and food to insects and the pirnkirrjarti (bush turkey), who is also lured by the tree’s golden marnta. These desert relations are central in the work of Walmajarri painter, Jimmy Pike (c1940 – 2002), in which he depicts Country from the perspective of ‘land use’, rather than landscape. Turtujarti kurrmalyi portrays the metaphysical, embedded and embodied relationships that come from living in a place, not simply the visible features of the land that can be grasped at a distance by looking through a frame. The painting is a projection of an embodiment of Country, everything is moving around, trees, animals, humans, the water, inhabiting the desert, stories and history too, cosmology, all coming out of the ground. [2]

Weaving traces between holes in the earth—open cut mines, waterholes, fracking wells, construction pits—this four-part essay scrutinises how ‘empty space’ is manufactured, what comes out of the ground and what happens when nourishing terrains are dug up to sustain cities. I use the term ‘city-desert dialectic’ operatively to digress into the muddy, asymmetrical relationship between the city and deserted, remote places. Following in the paths of others, I look to artists Jonathan Jones and Jimmie Durham to critique the notion of the city as ‘the centre’ of life, toward identifying ways that the city is indebted to remote places through resource extraction. Jack Green’s paintings Red Country (2017) attests that Country is a living entity, in response to open cut mining and Lauren Burrow’s Nuisance Flows (2019) swims against the current of ‘self-sufficiency’, realising the deeply implicated, multi-species relationships individuals have to peripheral places. In You Call it City — We Used to Live Here, I desire to produce a kind of antimyth of city life, seeing the Melbourne Metro Tunnel Project as a spectacle of development, which recreates the frontier (empty space) in the city.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Each city receives its form from the desert it opposes [3]

The desert changes and churns, grasses burn, rain comes and the land floods. It’s technically an area of land categorised by low average annual rainfall, its geographical location and in popular depictions is typically represented as a vast uninhabited space. Think of familiar tourism images, the orange earth engraved with an endless road, that long stretching emblem of frontier mythology, rousing the neo-colonial imaginary and promising ‘untouched’ land, removed from the commotion of the city. This deserted place isn’t just a receptive field in frontier mythology, it is operationalised materially as a site of extraction (iron ore and other resources taken from the earth) in the service of erection (urban development, towers).

Within the city-desert dialectic, deserted or ‘remote’ places are both a resource and a symbolically static space of absence, against which the city, the ‘centre’ (place of presence) maintains its economy and image. Lisa Robertson, in her essay ‘Disquiet’ poetically writes that in the city, ‘the means of living are what are extracted from an elsewhere’ suggesting that the city is defined in opposition to the places it relies on – for its profusion of essential services, products, entertainment and the other elements that make cities appealing places to reside—such as the far off places where mining happens. [4] The dichotomy produces a singular concept of place, imposing a hyperseparation between the city and the ‘elsewhere’ it relies on for support. [5]

The imagined hyper-separation of metropolitan and remote areas is conveyed by the colloquial settler expression ‘black stump’, which denotes the boundary of ‘civilised’ territory. The stump indicating beyond which the land is envisioned as remote or ‘uncivilised’, implying a centre/exterior spatial regime. More than a vernacular adage, actual ‘black stumps’ are physical markers—there are 11 situated around the continent, including one in Coolah, NSW, which claims to be the place the term originates, separating settlements (the peopled centres) from remote land.

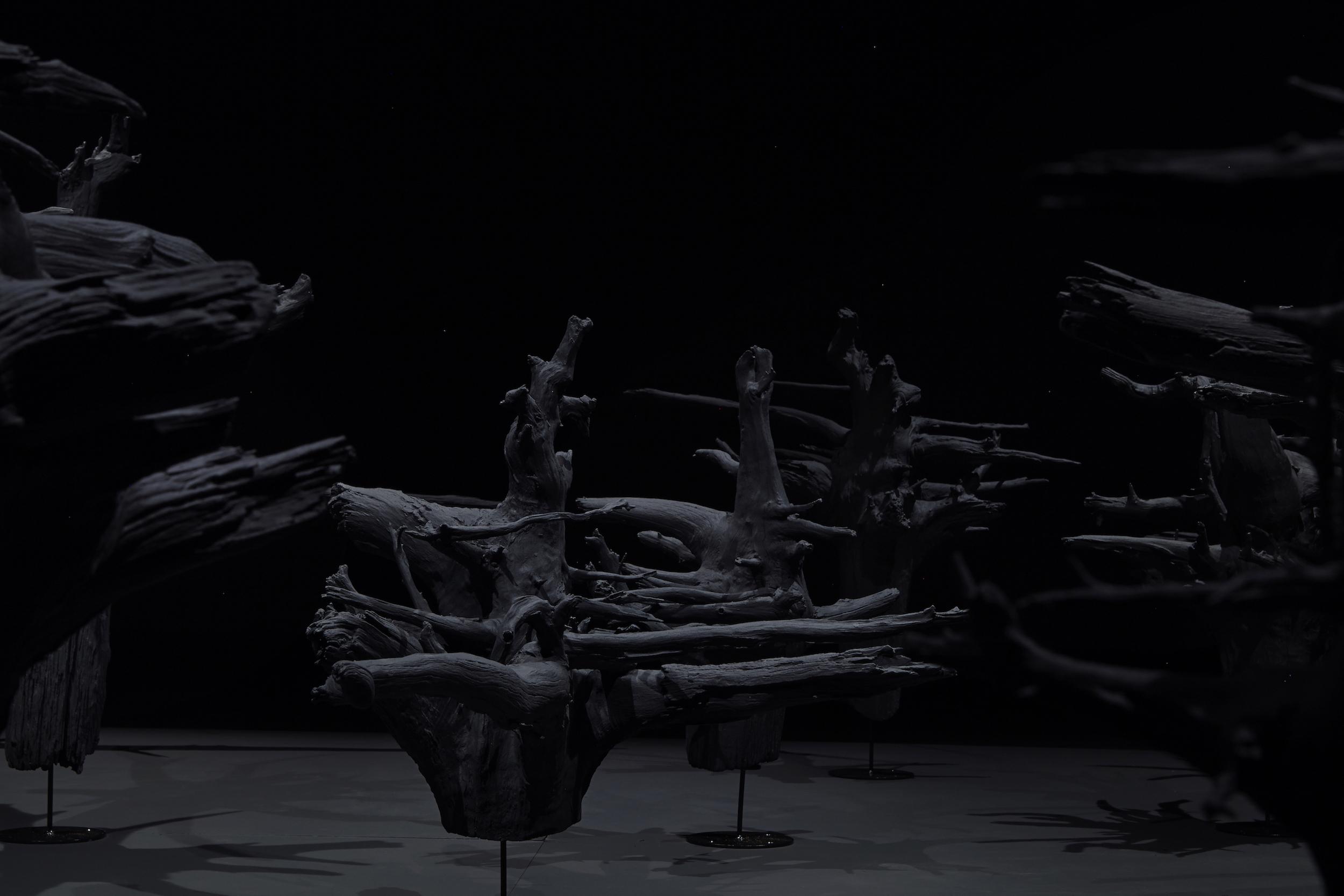

Jonathan Jones’ installation Guguma Guriin | Black Stump (2019), physically and semiotically inverts the term ‘black stump’. In Jones’ work 38 white cypress pine tree stumps, which have been dug out of the earth, roots intact, are painted in black charcoal and placed upside down in the gallery at Carriageworks, Sydney, dislocating the imagined boundary of civilisation that ‘black stump’ typically signifies. The industrial pine is commonly used in fencing, but Jones’ upended stumps, with their gnarled roots exposed in an elegiac gesture are a future message of looming ruin, signalling that in the economy of pine, product and refuse are inextricably waste. The stumps de-naturalise the spatial and economic logic of the settler city, collapsing the binary figuration of centre/outside, city/remote.

Like a footnote to Guguma Guriin, Jimmie Durham’s Anti Flag (1992) opposes the idea of myopic loyalty to a singular (centre) place, whether it’s a city or nation-state. In Anti Flag, capitalised text painted under a figurative tree on yellow canvas satirically suggests ‘THERE ARE SEVEN CONTINENTS, EACH HAS SEVEN SACRED TREES’ all of which ‘STAND AT THE CENTER OF THE WORLD’, provoking the reader to ‘FIND ONE THAT YOU LIKE AND PLACE YOUR OWN UMBILICAL CORD OR ITS EQUIVALENCE AMONG THE BRANCHES. DO NOT SALUTE’. Anti Flag, like Guguma Guriin, interrupts the authority embedded in mythologised artefacts, and moves toward recovering a multi-centred sense of place-based relations.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

All this gnawing at the existence of the colonized tends to make of life something resembling an incomplete death. [6]

The colonial organisation of space is a process of simultaneously making territories uninhabitable and inhabitable, marking out ‘who matters and who does not’. [7] This topography of cruelty is achieved by a physical, symbolical and administrative separation of peoples, land and life support systems enacted partly through the remote infrastructural control of water, housing, telecommunications, electricity, calories and so on. Cast an eye onto ‘remote’ Indigenous communities that exist in a state of siege. The targets here are not simply Indigenous lives or people, but Indigenous life, ways of being.

The places that aren’t settled (that ‘don’t matter’), specifically remote-controlled Indigenous communities live with the threat that the minimal necessary support for existence can be stripped away at any moment. As was the case with Oombulgarri, a remote Aboriginal community east of the Kimberly: in 2014 the Western Australian Government severed the community’s essential services, served eviction notices and then rolled bulldozers in to demolish the remaining infrastructure. [8] Then, the remnants of Indigenous life in Oombulgarri, were gathered together and buried in a hole dug by the government as a final gesture of enmity.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

It was everywhere – a gelatin – a slime – yet it had shapes, a thousand shapes of horror beyond all memory. There were eyes – and a blemish. It was the pit – the maelstrom – the ultimate abomination… it was the unnameable! [9]

Situated ethically, symbolically and socially outside the order of the city, what is impermissible or unthinkable in the metropolitan centre is transferred to ‘uninhabited’ remote places. From testing nuclear weapons in Maralinga, the threat of the Carmichael coal mine poisoning Doongmabulla Springs, to fracking, set to cause destruction all along Roper River, the city is symbolically amputated from its multiple places of ‘economic and ecological’ maintenance. [10]

Yet, the city itself is no more a centre than these places it materially relies on. In her perceptive ‘unsettled Settler response’ to ‘Open Cut’ (2018), an exhibition at the Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA) in Darwin, Kate Leah Rendell contemplates Red Country (2017) a painting by Garawa artist Jack Green. [11] In Red Country a dark, oblique shape conveys the sinister ambience of a pit mine, which is encircled by waterways, a turtle, a tree, a bird, serpents, worldly actors with meaningful connections to the land, painted on a red background:

‘In certain interpretations it may be possible to read the dark shape as natural – not unlike a waterhole or rock formation. But there’s something unmistakably ominous about the depth of blackness. In mining language this open cut pit is known, almost poetically, as the “void”.’ [12]

Transposing the ‘natural’ and ‘unnatural’, Red Country isn’t so much about competing modes of interpretation as it is about land use, recognising the deep cultural history of a place in the context of its contemporary exploitation. Green knows Country, its palimpsestic stories, histories, ecology, how it responds to the mine. What makes Green’s attachment to Country distinct from a singular notion of belonging in settler city, is a deep cosmological, material and reciprocally nourishing connection: Country is the very place that sustains him and the place which he is obligated to sustain in return. [13]

‘Right in the middle of this sacred country is a torn-up place’, Green articulates, alluding to environmental destruction caused by the McArthur River Mine, near Borroloola, which damages ecological communities and wounds the land, but can never totally consume Country. In conversation with the waterhole of Jimmy Pike’s Turtujarti kurrmalyi, both painters portray holes that are literally grounded in Country signalling to different modes of being manifest in divergent patterns of land use. The waterhole sustains turtujarti trees and as such a web of ecologically connected life; while the pit mine supplies zinc for a range of consumer goods, maintaining a network of economically connected activity.

Zinc and other resources flow into the city as waste is expelled. Coal in its various useful guises - electricity, carbon fibre, toothpaste, kidney dialysis machines; iron ore in steel, construction, paperclips; lead in car batteries; lithium in ecofriendly car batteries; gravel and limestone in concrete (the second most consumed substance in the world, behind water). The consumption of these products and others creates effluent, which is purged, further implicating the city in its dependence on a network of unseen, deserted places.

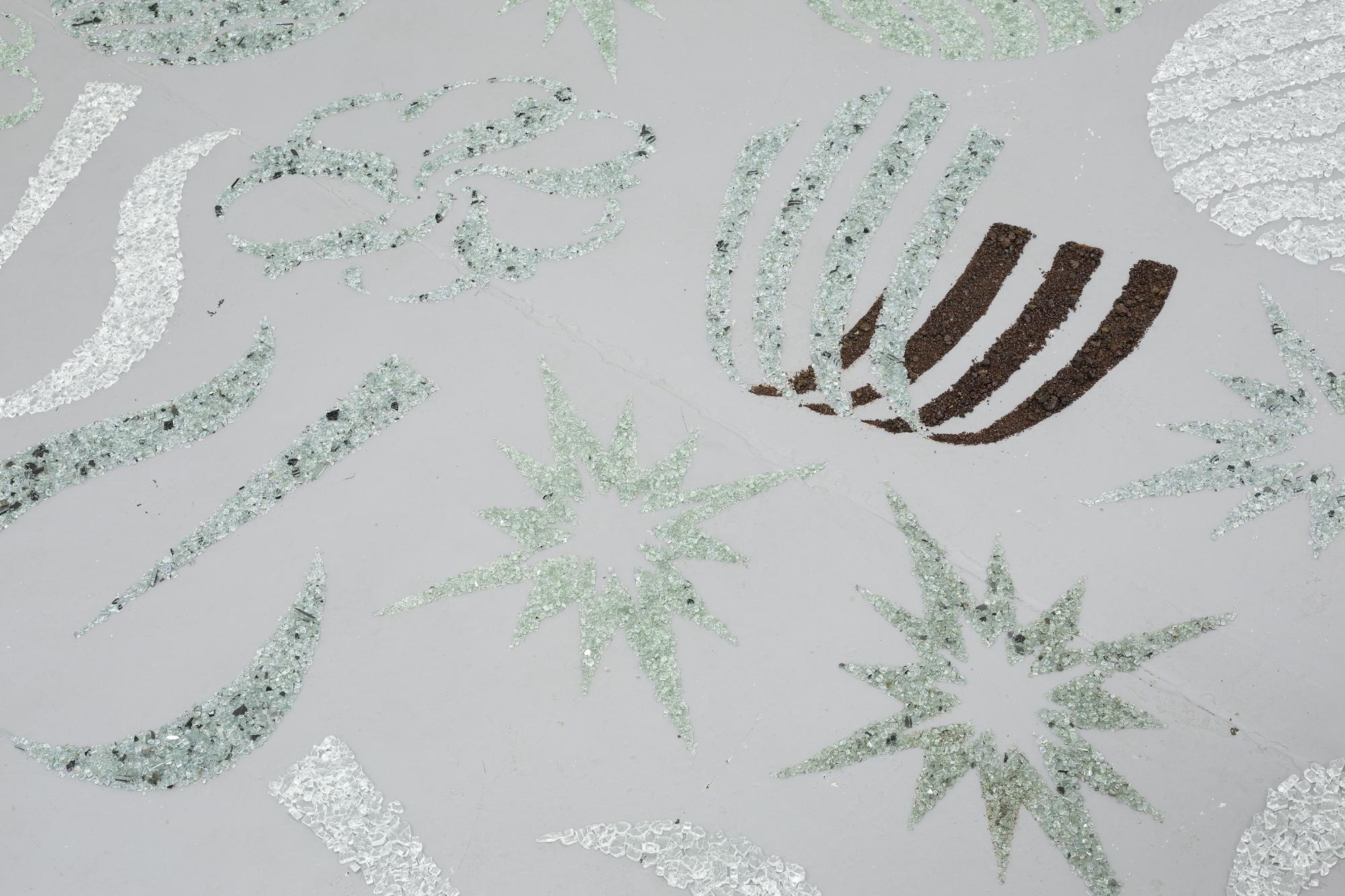

These deserted places are delineated by the city’s ecological imprint. In Melbourne, eucalyptus trees protruding from bitumen-sealed carparks and concrete footpaths can be seen oozing red-gold sap, trying to expel the threat posed by parasitic longhorn beetles, which bore trails in the trees’ bark to lay their eggs. Lauren Burrow’s exhibition Nuisance Flows at TCB artinc., places amber crystals of this eucalyptus resin on the gallery floor, mingling with shattered safety glass from broken car windows. [14] Shattered glass and eucalyptus resin are detritus of ruptured surfaces. The glass and resin pieces are arranged to make glistening silhouettes of antidepressant brand logos—a Prozac globe, Zoloft star, etc. In the gallery, the logos sparkle with the green and white hues of fresh water when the sun hits, alluding to scientific studies that have shown that antidepressants seep into aquatic ecosystems and are absorbed by fish, making them more vulnerable to predators.

Nuisance Flows grasps the dissociation that permeates global consumption, which enables us to imagine we can be consuming-in a singular dwelling place and brings to mind disregarded places of ecological dependence. Put concisely by Helen Hughes in Artforum, ‘Nuisance Flows provokes the viewer to attend to the multiple ways capitalism implicates its subjects in downstream multispecies relationships and ecological destruction.’ [15]

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

How negative space is created can be more important than what’s constructed from its departed materials elsewhere [16]

Departed materials—iron, coal, gravel—and negative space converge in the Melbourne CBD. Cavernous holes, such as the one currently at the corner of Flinders and Swanston Streets have been made using excavation machines, bulldozers, and trucks to dispose of the muddy earth, concrete, iron rods and architectural debris. A part of the ongoing Metro Tunnel project (owned by Rail Projects Victoria (RPV)), the site will become an underground train station. With the promise of unhindered movement and increased productivity in the city for a burgeoning population, the pit connects to prosthetic arteries, dug by Tunnel Boring Machines (TBM) cladding hollows with cement as they dig, mining an underground cartography.

Intent on creating a highly visible symbol of development, the hole is complimented by a creative program and an exhibition space . On display at Metro Tunnel HQ, which resides in a large shopfront on Swanston Street, are archaeological finds, mythologised artefacts of settler life in the 1800s. [7] Extracted from the earth are old wine glasses, coins, pencils, a pen nib, personalising settler history for the HQ attendee. These quotidian remains evoke the sense of unhindered connection between historical and contemporary settler presence, with the city as its axiomatic precondition.

The exhibition of these objects, like the proposed rail network, attempt to overcome history by design—the unhindered movement of people and objects through space and time. In contrast to the industry and technology represented by the scale model TBM and the virtual reality site tours offered in Metro Tunnel HQ, the artefacts reassert themselves in the present as anodyne remnants of domesticity, charming markers of settlers belonging to the city, and the city belonging to settlers. Describing the hole in 2018, writer and Trawlwoolway descendent, Neika Lehman suggests it is a “monument, maybe even a temporary memorial” to settler-colonialism in the city. [18]

Less public is the project’s ‘Environmental Effects Statement’, which claims the tunnels are too deep to contain ‘potential archaeological deposits containing Aboriginal cultural material’, despite the fact that the land and the earth themselves are intrinsic to Aboriginal land use practices, history, culture, cosmology. The underground is transformed into a conflict zone, in which Indigenous and settler conceptions of land and history are revealed to be incompatible. Green’s words resound as the RPV tears up the earth, right in the middle of Country. [19]

In the city of Melbourne, the frontier operates on a vertical axis. The hole in the earth and the building in the sky maximise space in which the material and symbolic manifestation of settler ideology takes place. Simultaneously, the crater exposes the city as an overlay of material, economic and social organisation. Although the city is dominant mode of spatial control, it cannot totally consume the Country in which it is situated or that it relies on for resources.

Country is lived in and with across superimposed landscapes, never an undifferentiated place or a distant image, it respires and responds. It’s a dirty, wet, clouded amalgamate of soil, water, sky, people, animals and plants, kin, with its own history. Country provides an antimyth to the binary spatial regime and its attended cladding, concrete, bitumen, steel, the TBMs charting a subterranean frontier. However thoroughly mapped or policed city borders and buildings are, Country is precedent and persistent in the ground that the city is sheathed over.

[1] The title of this text is borrowed from Pat Lowe and Jimmy Pike’s You Call it Desert — We Use to Live There, (originally published in 1990), Magabala Books, Broome, 2017.

[2] Deborah Bird Rose, Dingo Makes Us Human, Life and land in an Aboriginal Australian culture, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, p. 57.

[3] From Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver, Secker & Warburg, London, 1974, p. 15. Marco Polo describing the imagined city of Despina to Kublai Khan speaks of two travellers, one who arrives overland and the other by sea. Over the horizon, a camel driver sees the city as a ship that will take him away from the desert and as the coastline of Despina appears to the sailor, he thinks of the city as a camel that will carry him away from the ‘desert of the sea’. Each traveller projects onto the city the reverse image of the desert that they have travelled through, a fantasy which entails the travellers being carried by the city away from itself, into the ‘unknown’. In this sense, the city emerges as a frontier interstice, a hyphen between the conquered and the conquerable.

In the next section of Invisible Cities a traveller returning from the invented city of Zirma, recalls memories, which are discordant with those of his companies. His memory has multiplied and repeated city events and features (the known) in order to displace the unknown of the city. So the city repeats itself, so as to produce an image of itself.

[4] Lisa Robertson, ‘Nilling: Prose (Department of Critical Thought)’, BookThug, 2012, p. 69.

[5] Val Plumwood, ‘ Shadow Places and the Politics of Dwelling’, Australian Humanities Review, 01 03 2008, http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2008/03/01/shadow-places-and-the-politics-of-dwelling/; accessed on 17 March 2020.

[6] Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism, originally published in French as L'An V de la Révolution Algérienne (Year Five of the Algerian Revolution) (1959), trans. Haakon Chevalier, Grove Press, New York, 1967, p. 128. The book is an incisive document of Algerian ingenuity and initiative to adapt cultural practice in the resistance against French colonial oppression.

[7] Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, 2011, Duke University Press, Durham, p. 27.

[8] See Gerry Georgatos, ‘“We want to go home” but Government to demolish Oombulgarri’, The Stringer, 24 June 2014. https://thestringer.com.au/we-want-to-go-home-but-government-to-demolish-oombulgarri-7953#.Xl7kpBMzbOQ

[9] H.P. Lovecraft, ‘The Unnameable’, Black Seas Of Infinity: The Best Of H.P. Lovecraft. New York: SFBC Science Fiction, 2000. p.428. ‘The Unnameable’, originally published in 1925 in Weird Tales an American pulp magazine, is a horror short story. The protagonist, Carter meets a companion in a cemetery and as the two sit on a tombstone, Carter speaks of an ambient presence that haunts the area, suggesting that because the entity cannot be perceived by the five senses, it is impossible to accurately describe, quantify or name.

[10] Plumwood, 2008

[11] Kate Leah Rendell ‘An unsettled Settler response to Open Cut', Un Magazine, 12.1, 2018.

[12] Jack Green, Open Cut, Exhibition Program, Northern Centre for Contemporary Art (NCCA), Darwin, 2017.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Lauren Burrows, Nuisance Flows, TCB artinc., February 2019.

[15] Helen Hughes, Review of ‘Nuisance Flows’, Artforum, Summer 2019. https://www.artforum.com/print/reviews/201906/lauren-burrow-80004; accessed 17 March 2020.

[16] Lucy R. Lippard, Undermining, A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West, The New Press, New York, 2014, p.34. Concerned with the gravel pits that pockmark the west coast of the United States, Lippard’s book engages in cultural geography, winding through the competing and conflicting land use practices across America.

[17] Metro Tunnel HQ is located in proximity to the ‘dig’ on Swanston Street in close proximity to the site. https://metrotunnel.vic.gov.au/contact/metro-tunnel-hq.

[18] Neika Lehman, ‘”(In)visible Expansions: the Big Hole as Monument:” Working the Memorial: Current Research and Practice: Neika Lehman, University of Melbourne; Yhonnie Scarce & Jessica Neath, Monash University’, Aesthetics, Politics and Histories: The Social Context of Art 2018 AAANZ Conference, RMIT School of Art, 2018. Now shrouded by a ‘shed’ the Swanston Street, the hole is obscured from sight – development enters its next stage. Lehman’s work is vital in insisting that the hole – a mundane yet violent colonial artefact – not recede from memory, holding the passer-by historically accountable for their ‘everyday complacent consciousness’.

[19] The Metro Tunnel project covers a vast area, across a number of First Nation’s territories, including unceded Boonwurrung and Wurundjeri lands. The Melbourne Metro Rail Project ‘Environmental Effects Statement’ (2016) and other information regarding the project can be found online at metrotunnel.vic.gov.au.