Remembering Australia’s Queer Places: An Updated Prologue

By Richard Peterson

My 2015 paper described 45memorials. [1] But another 82 have been located in the past five years: so now a total of 127 memorials are known. All 127 are listed below (with a few others that remain as proposals), but details are only given here for the 82 additional places.

Thanks particularly to Nick Henderson of ALGA for his documented suggestions of further memorials. [2]

Queer memorials appear in a diversity of forms, commemorate a range of concerns, and are funded by public donation, or philanthropy; or by government, or municipal grants. Vandalism has been a problem in some instances, and even complete removal by antipathetic government.

Most of these memorials commemorate those lost to the AIDS epidemic, but also to oppression, or their deaths resulting from political, military, or police action. And there is another range of markers which commemorate historical individuals, initiatives, events, or movements.

The memorials take an imaginative range of forms: a water basin, pool, or fountain; a single tree, or a grove of trees; a seat, a pathway, a stairway, a field of plinths, a garden, or park (often small, but two are as large as a hectare, and another even three-hectares). Often there will be a plaque fixed to a building (where someone lived, or something happened), or a sequence of plaques (or ‘cobblestones’) on a pavement, or footpath; and most successfully of all, as a quilt of panels. Streets, squares, steps, walls, or a bandstand, or pavilion may be named for significant people.

The memorials are often with inscribed names (sometimes very many), even bas-relief faces of victims, or of heroes, or in a book of remembrance (whether physical or virtual). Sculptures are a frequent choice, some of high quality and very fine and moving; others less so; or utilizing stained, or engraved glass; or as installations, sometimes interactive; a tombstone, even within a cemetery; incorporating candles, and at least once, especially composed music. There are also several audio podcast apps, either freely available, or for a fee, which describe places of historic significance along a trail. Several memorials have their own supplementary website. Queer people are not short of imagination!

A. Existing International Queer Memorials and plaques [3]

Austria

1. Der Rosa Platz, Vienna, 2007.

This is now open. [4]

Australia

Sydney

2. SPAIDS (Sydney Park AIDS Memorial Groves).

3. Queer Holocaust Memorial, Sydney.

4. The Chequerboard House, Balmain, Sydney.

5. The AIDS Memorial Quilt. The Names Project Foundation. [5]

Also refer: AIDS Memorial Quilt Project, Thorne Harbour, Melbourne (below).

6. Darlinghurst Road, 100 Plaques. The Strip on the Strip. City of Villages.

The stories that inspired the bronze street plaques of Kings Cross, City of Sydney, 2007. [Brochure].

Relevant are: Les Girls, 1964 p 15; Sydney's First Mardi Gras, 1978, p 25. [6]

[Bondi Memorial Project, Marks Park, east end of Fletcher St, Mackenzies Point, Tamarama, Sydney.

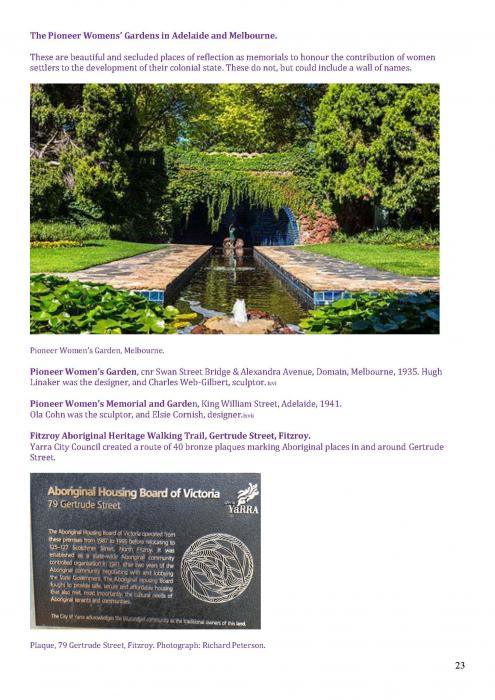

It was proposed by ACON, and active from 2016-18, but nothing has been posted about this project since June 2018]. [7]

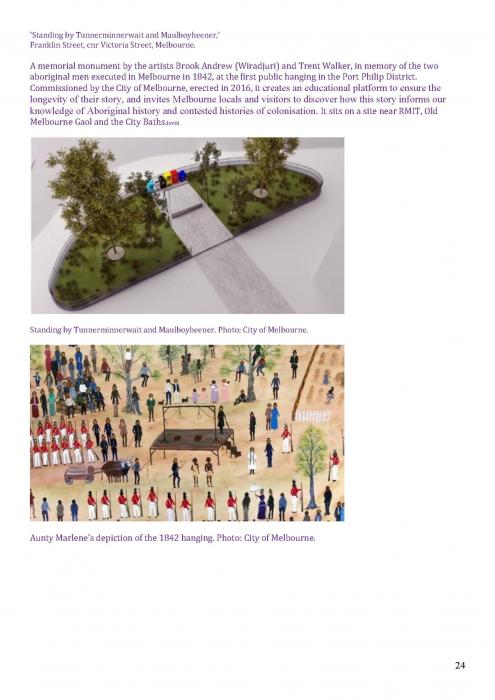

Newcastle

7. Community Memorial Park, Carrington. Seat and trees, 2005.

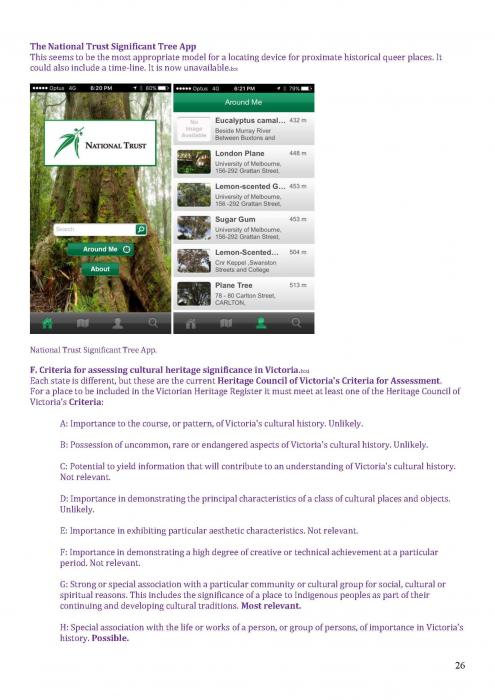

Community funded. It commemorates the 150 local young people who died of AIDS. [8]

Melbourne

8 (6). AIDS Memorial Garden, NMIT's Fairfield campus (formerly Fairfield Hospital).

9. 'Courage,' a public sculpture in bronze, at 209-217 Napier Street, Fitzroy, by William Eicholtz, 2014.

The work was inspired by the Cowardly Lion in the The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and the courage to be yourself, whoever you are. It honours the contribution, culture and diversity of the GLBTIQ community, and commemorates Ralph McLean (1957-2010), Australia’s first openly gay elected official (City of Fitzroy, 1982), and Mayor (1984), advocate for gay rights and social justice, and for the arts. At night the base of the sculpture lights up with its own yellow brick road. [9]

10. HIV/AIDS Mosaic, small courtyard, Fairfield House, Alfred Hospital, artist: Anne Riggs, 2001. [10]

Possibly the Fairfield House courtyard was broadly designed, or intended as a memorial, but this is unclear. [11]

11. The Shards, Positive Living Centre (PLC), 51 Commercial Road, South Yarra.

This includes names of some people who have died to the virus. [12]

12. The AIDS Memorial Quilt. The Names Project Foundation, part is located at the AIDS Memorial Quilt Project, Thorne Harbour, Melbourne.

The Australian quilt is located in various separate places, and Melbourne's is an entirely separate holding to the Sydney panels. The Adelaide panels are also held in Melbourne. There are also additional organisations for quilt panels in Perth, Newcastle; and possibly Brisbane and Darwin. The Australian quilt has not been entirely digitized and is not generally on public display in any way. [13]

[Victorian Pride Centre, Fitzroy Street, St Kilda, 2019-20.

At time of writing, the Victorian Pride Centre continues to work towards how it marks, acknowledges and commemorates LGBTIQ histories and communities through physical elements within the building, activation of the spaces, and collaboration and support of its resident organisations]. [14]

Adelaide

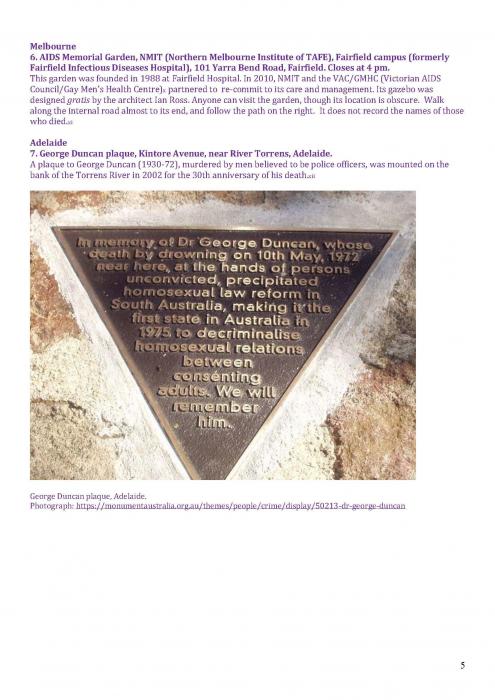

13 (7). George Duncan plaque.

Perth

14. AIDS Memorial, Stuart & Fitzgerald Streets, Robertson Park, North Perth.

Designers: Rodney Glick, Diego Ramirez and Kieran Wong, c2000.

Funded by the City of Vincent, the Australian Council for Arts, and local businesses. But not identified on site, nor in the City of Vincent website, and physically neglected. [15]

Hobart

15. Salamanca Memorial, The Yellow Line, Salamanca Place. Artist: Justy Phillips, 2008.

Commemorates the City of Hobart’s public apology for several arrests at Salamanca Market in 1988. [16]

Canberra

16. AIDS Garden of Reflection, National Aboretum, Forest Drive, off Tuggeranong Parkway,

Weston Creek. Designed by John Patrick Landscape Architects Pty Ltd, 2017.

This was advocated and community-funded by some people living with HIV, their families and friends, the AIDS Action Council, and their patron John Mackay AM. [17]

Canada

Ottawa

17. AIDS Memorial Quilt, held by the Canadian AIDS Society, 170 Laurier Street, Suite 602, since 2013. [18]

Toronto

18. AIDS Memorial, Barbara Hall Park, 33 Monteith Street.

Temporary in 1988 with 200 names, but permanently opened in 1993.

Architect: Patrick Fahn. A memorial garden with plaques inscribed with victims' names. [19]

Vancouver

19. Vancouver AIDS Memorial, on the seawall overlooking English Bay between Sunset Beach and English Bay Beach, Stanley Park.

Lists all the names of those who died. [20]

20. AIDS memorial, Devonian Harbour Park, Coal Harbour, near Stanley Park, near Denman Street, West Georgia, 1985.

Four cherry trees were planted in the memory of four men who died of AIDS, fearing homophobia, discretely located, identified only by their first names. [21]

Winnipeg

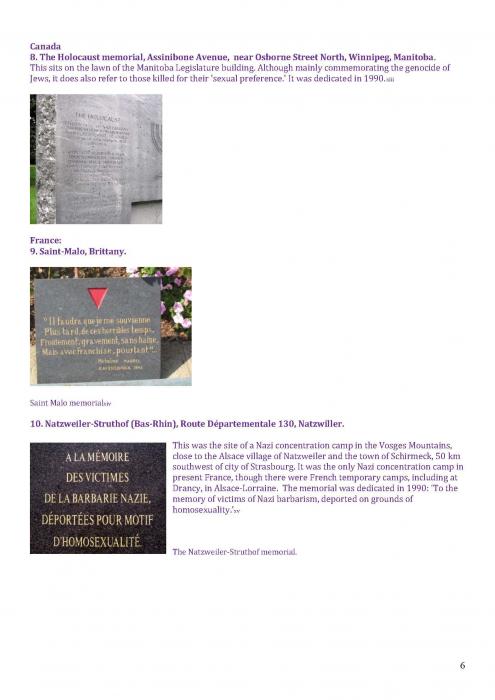

21 (8). Manitoba, Winnipeg.

France

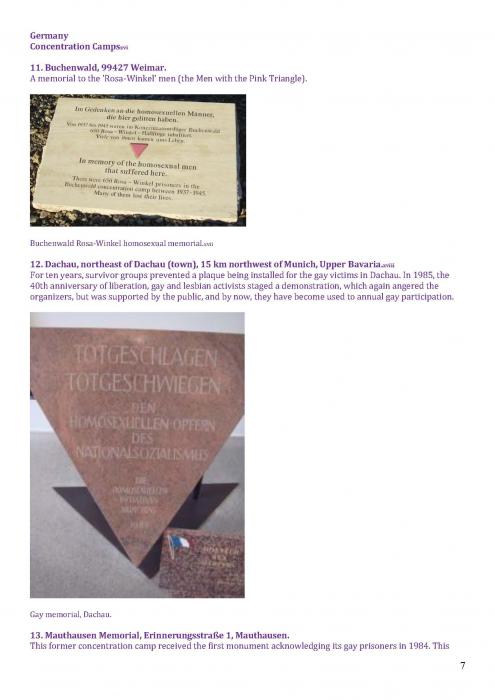

22 (9). Natzweiler-Struthof.

23 (10). Saint-Malo.

24. Les Marches de la Fierté (Pride March), Nantes, 2018.

Many cities (including Melbourne and Sydney) have rainbow painted pavements, or as here, a stairway; but this has one been vandalised several times, and which the City of Nantes has then reinstated. [22]

25. Père Lachaise Cemetery, Boulevard de Ménilmontant, Paris.

There is no particular monument in Paris, but this is an unofficial pilgrimage place to the graves of Gertrude Stein & Alice B Toklas, Colette, Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde. [23]

Germany

22 German cities now have AIDS memorials. [24]

Concentration Camps [25]

26 (11). Buchenwald

27 (12). Dachau

28 (13). Mauthausen

29 (14). Neuengamme

30 (15). Sachsenhausen

Berlin

31 (16). Memorial to Homosexuals persecuted under Nazism, Tiergarten Park.

32 (17). Memorial plaque at Nollendorfplatz

33 (18). Stolpersteins

Cologne

34 (19). Cologne.

Frankfurt am Main

35 (20). Frankfurt am Main

36. Heidelberg, 2006.

A discreet black obelisk with a red ribbon stands in memory of the victims of AIDS, inside a cemetery. [26]

37. Kassel, 1992. [27]

38. Munich, Sedlinger Tor, 2002.

A tall blue cylindrical column. [28]

39. Nuremberg

Nuremberg community commemoration, Magnus-Hirschfeld Platz.

A memorial garden, rainbow seat and small monument for homosexual victims of National Socialism. It was redesigned in 2019. [29]

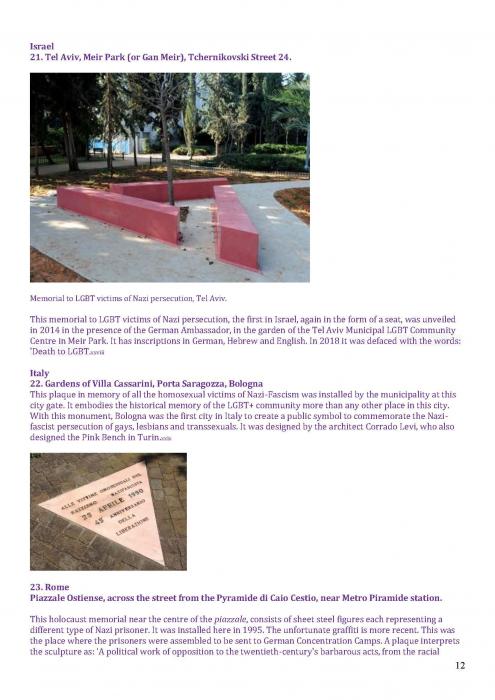

Israel

40 (21). Tel Aviv.

Italy

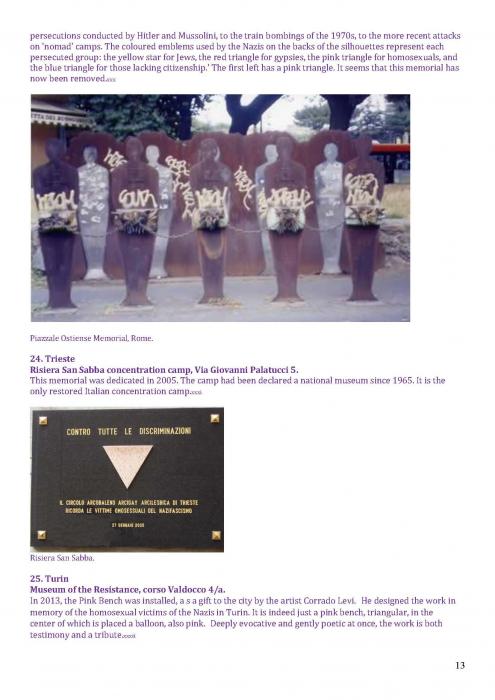

41 (22). Bologna.

42 (23). Piazzale Ostiense, Rome.

43 (24). Trieste.

44 (25). Turin.

The Netherlands

Amsterdam

45 (26). Amsterdam,1987.

46. HIV/AIDS Monument on the IJ, De Ruyterkade Northwest, corner of Oosterdokseiland.

An initiative of NAMENproject Nederland, 2016. Artwork by French artist

Jean-Michel Othoniel: 'Living by Numbers', which was funded with philanthropic support, the City of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Hospital, a commercial sponsor and crowdfunding. There are still 22,900 people with HIV in the Netherlands, and another 2,800 who don’t know they have it. Christina Della Giustina has written a musical score for the monument. [30]

47. The Dutch Quilt. The first panels were made in 1987, and in 1993 the NAMES Project Netherlands was founded. [31]

48. Tree of Life, centrale hal (Central Hall, in one corner), Amsterdam Medical Centre, a hanging sculpture by the Mexican artist Ricardo Regazzoni,1991. [32]

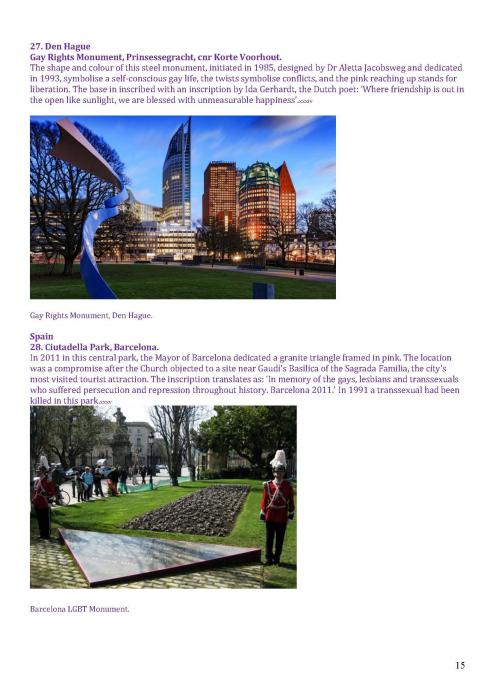

Den Hague

49 (27). Den Hague.

New Zealand

Auckland

50. Circle of Friends Memorial Garden, Kanuka Grove, Western Springs Lakeside Park.

Names are inscribed in nine circles, and these also appear on rotation on the website. The memorial was established by Body Positive Inc (Tinana Ora Aotearoa), and is interactive and allows others to add an engraved plaque to the stone circle. [33]

51. New Zealand AIDS Memorial Quilt, 1988. Unveiled 1991.

The entire quilt is available for viewing on the website. [34]

52. New Zealand Book of Remembrance, c/o: PO Box 6663, Wellesley Street, Auckland, 1994. [35]

53. Tree of Remembrance, Constitution Hill, by the Auckland Community AIDS Services, 1991. 'Near the top of the path leading down the hill, on the left as you go down.' [36]

Poland

Warsaw

54. Tęcza, Rainbow Monument, Savior Square. [37]

The previous rainbow was made of flowers and erected in 2012 and maintained by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, before finally being removed in 2015 after repeatedly being vandalised. The second was erected in 2018, but survived only a few hours. The current and third light rainbow was sponsored by ice-cream company Ben & Jerry’s. which has supported LGBT causes in the past.

Russia

55. Moscow, 2004. [38]

56. Svetlogorsk, 2008. [39]

South Africa

57. Durban

AIDS Ribbon Sculpture Monument, Gugu Dlamini Park, 2000, artists: Jeremy Wafer and Georgia Sarkin; and mosaic artist, Clive van der Berg.

An additional Wall of Hope was opened later that year. Gugu Dlamini was a local woman stoned to death by men for being HIV+ in 1998. [40]

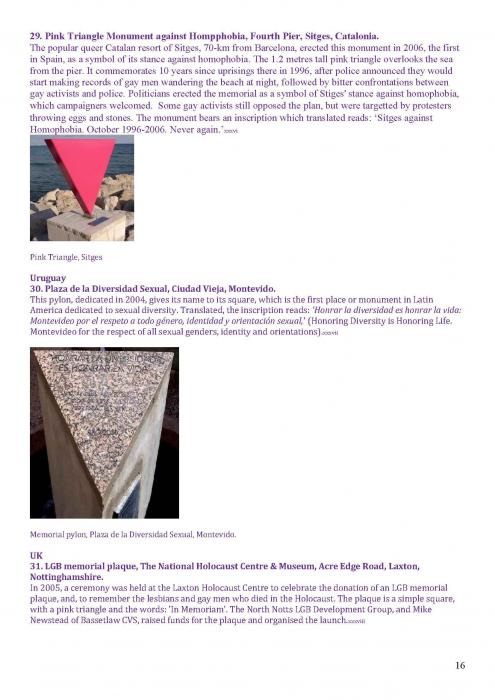

Spain

Barcelona

58 (28). Barcelona

59. Glorieta de la transexual Sònia, Parc de la Ciutadella.

This bandstand is in memory of Sonia Rescalvo Zafra, a transsexual who was murdered by a group of Neo-Nazis in the park in 1991. This incident became a turning point in public attitudes towards transsexuals in Spain. [41]

60 (29). Sitges, Catalonia

Madrid

61. Plaza de Pedro Zerolo (Plaza Vázquez de Mella), Madrid [42]

Designed by the Italian architect Teresa Sapey, inspired by Dante’s Fifth Canto from The Divine Comedy (c1308-20), the red ribbon sculpture is installed over the entrance of Chueca an-Dante Parking. [43]

Durango

62. Monolito en memoria a las personas represaliadas por el franquismo por su opción sexual, 2009. [44]

Fuerteventura

63. Monuments in the Colonia Agrícola Penitenciaria de Tefía. [45]

Gijon

64. Bosque de la Memoria de Asturias, 2010. [46]

A memorial monolith. [47]

Huelva

65. Placa homenaje a los homosexuales encarcelados en la cárcel de Huelva, 2005. [48]

Mallorca

66. Palma de Malloeca, 2007. [49]

Catalonia

67. Sabadell, 2005. [50]

UK

68. Bournemouth, Pier Approach Underpass, 2010.

A memorial for the 400 who died from AIDS in the County of Dorset, depicted in tiles that were created by Dorset Aids Memorial Schools Educational Trust. [51]

Brighton

69 (33). Gay & Lesbian History Trail.

70 (34). The Pink Plaques tour.

71. Brighton & Hove AIDS Memoria, New Steine Gardens, 2009. [52]

A 4-metre high bronze sculpture, by Romany Mark Bruce.

Edinburgh

73. 'Life Tribute' Edinburgh AIDS Memorial, Water of Leith Walkway, 2004.

Between the exits for Dean Gallery and the Gallery of Modern Art, opposite the staircase up to the National Gallery of Modern Art, with a seat, and inscriptions in stone. [53]

Laxton

74 (31). Laxton, Nottinghamshire.

London [54]

75. Oscar Wilde memorial: A Conversation with Oscar Wilde Adelaide Street, cnr Duncannon Street, Charing Cross, sculptor: Maggi Hambling, 1998.

There is another Wilde memorial in Dublin. Both of these memorials invite a physical response. [55]

76. A simple black plaque marks the spot where the first ever gay rights protest took place in London, in Highbury Fields, in 1970.

77. Alan Turing Memorial, south end of St Mary's Terrace, Paddington, 2013.

78. 130 years of Queer Soho (or thereabouts. Take a virtual tour), London, Historic England.

A walking app which guides users through 16 places associated with the 'alternative lifestyles' (all queer) of this area’s residents over the past 130 years. [56]

Manchester

79 (32). Manchester.

80. Alan Turing Memorial, Sackville Park, near Canal Street, 2001.

A seated figurative bronze sculpture, for which funds were raised by an appeal, but no artist is mentioned. [57]

81. Alan Turing statue, Bletchley Park, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, artist: Stephen Kettle, 2007.

There are four Turing memorials, the others are in London, and Eugene, Oregan. [58]

Ireland

Dublin

82. Oscar Wilde memorial, Merrion Square, artist: Danny Osborne, 1997.

It is located near to the house where Wilde grew up in from 1855-73 at 1 Merrion Square, where his parents continued to live, and which also has a plaque. There is another Wilde memorial in London. [59]

Ukraine

83. Kyiv, 2001. [60]

Uruguay

84 (30). Montevido

85. Plaza de la Diversidad Sexual (Plaza of Sexual Diversity), Montevideo, 2004.

The plaza and its large triangular pink granite monolith, were unanimously supported by the city legislature. [61]

USA

Alaska

86 (35). Anchorage.

Illinois

87 (36). North Halstead Street Legacy Walk, Chicago, 1998.

The first USA city to designate a district as LGBTQ, with the installation of 20 rainbow pylons.

In 2012, this became Legacy Walk, when plaques were installed on the pylons commemorating queer individuals, both international and local. [62]

88. AIDS Garden, The Belmont Rocks, south of Belmont Harbor, Lake Michagan, Chicago, 2018-20.

Supported by the Chicago Parks Foundation and the Chicago Park District, the garden is built on a hectare of the shore of Lake Michigan at the original location of the Belmont Rocks. This was where the local gay community gathered between the 1960-2000. It includes 'Self Portrait', a 9-metre high sculpture by Keith Haring. The Rocks were a political statement symbolising the right for gay men to openly exist outdoors when bars still had blackened windows. In 2003, the Belmont Rocks were bulldozed, and removed as part of a foreshore stabilisation project. [63]

89 (37). LGBT Veterans’ Monument, Elwood.

Oregon

90. An Allen Turing memorial, in hammered copper wall-mounted sculpture, University of Oregon, Eugene, 1988. [64]

New York City

91 (38). Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn.

92. Gay Liberation Monument, Christopher Park, Manhattan, 1992. Artist: George Segal. [65]

93. LGBTQ Memorial, 12th Street & Bethune Street, Hudson River Park, West Village, New York, . Artist: Anthony Goicolea, 2018.

This recognizes those lost in the Orlando Pulse nightclub shooting in June 2016, as well as all victims of hate, intolerance and violence. [66]

94. New York City AIDS Memorial (formerly the Infinite Forest), northwest corner of St Vincent’s Triangle Park, Greenwich Avenue, West 12th Street & 7th Avenue South, West Greenwich Village, designed Studio a+i, with its granite pavers by the famous artist Jenny Holzer,

2011-16.

It is adjacent to the former St. Vincent’s Hospital. 100,000 people have died of AIDS in New York City. [67]

95. New York AIDS Memorial, near Bank Street, New York, 2008.

A 13-metre long curved stone bench on a granite path in a landscaped knoll. The path is complemented by a balcony that juts out over the river where the famous Pier 49 was, utilising its piles, which are still visible above the water. [68]

96. Stonewall National Monument and Christopher Park, Manhattan (see below).

Florida

97 (39). Palm Springs, Florida.

98. Key West AIDS Memorial, White Street, corner Atlantic Boulevard, Key West, on the walkway approach to White Street Pier, 1997. [69]

1,000 names are inscribed in the granite pavement.

99. Love Grove, AIDS Memorial Project of Northeast Florida (AMP), Willow Branch Park, 2870 Sydney Street and Willow Branch Creek, Jacksonville, Riverside, Florida.

A non-profit organization raised donations for a memorial, a conceptual landscape plan was prepared, and 100 memorial trees were planted in 2019. [70]

Indiana

100. AIDS Memorial, 700 West 38th Street, Crown Hill, Indianapolis, Cemetery, 2000.

This is inscribed with names on tablets. [71]

Louisiana

101. New Orleans AIDS Memorial, 'The Garden Wall', Washington Square Park, Dauphine Street, cnr Elysian Fields Avenue, Faubourg Marigny, New Orleans, artist and glass sculptor: Tim Tate, opened 2008.

This utilized some public money, but was mostly funded by donations. It consists of faces, and is inscribed with many names on the pavement. [72]

Massachusetts

102. Provincetown AIDS Memorial, sculptor and installation artist Lauren Ewing, 2013-18. [73]

Missouri

103. Transgender Memorial Garden, 1469 South Vandeventer Avenue, cnr Hunt Avenue, The Grove, St Louis, 2015.

For transgender people killed by anti-LGBTQ violence. It was the first memorial in the world for anti-trans violence.

New Mexico

104. AIDS Memorial Chapel, Center for Action and Contemplation, Albuquerque, 2000.

Formerly the Damien Brothers Community, whose ministry was with HIV/AIDS, it is an etched glass window dedicated to those lost. [74]

Ohio

105. Natalie Clifford Barney Historic Marker, Cooper Park, next to the Metro Public Library, Dayton, 2009.

Barney was born in Dayton. This is one of the 1,300 historic markers in Ohio. [75]

California

San Francisco

106 (40). Pink Triangle Park, San Francisco

107. National AIDS Memorial Grove, de Laveaga Dell, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, 1991.

This was created by volunteers. Then in 1996, Congress and the President of the United States designated this site as the USA National AIDS Memorial. In 2019 the NAMES Project Foundation and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced that the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt will be on permanent display here from 2020. The Project's archives were gifted to the joint care with the American Folklife Center at the US Library of Congress, allowing for greater public access. This returns the quilt to San Francisco, where the project began. In 2001, Global Quilt was founded by Deny de Jong of Ideël+ and Jeff Bosacki of the International AIDS Prevention Initiative (IAPI) in New York, to keep alive the memory of those lost to AIDS worldwide. In 1989 the Quilt was nominated for the Nobel Prize, the largest ever community art project.

Apart from the Australian, Canadian, Netherlands, and New Zealand quilts listed here, there are quilts (not all still active) in Austria, [76] Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Denmark, France, Germany, Guam, Guatemala, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Nigeria, Northern Ireland, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, [77] South Africa, Spain, Suriname, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan ROC, Thailand, Trinidad & Tobago, Venezuala & Zambia. [78]

108. Harvey Milk Plaza (a transit plaza at the Castro Muni Metro Subway Station), 1985.

In 1997, a flagpole commemorating Milk was added, which flies the rainbow flag, and photographs of Milk's life (1930-78) were installed. [79]

109. Harvey Milk's store, Castro Camera, 575 Castro Street (between 18th & 19th streets), which he opened in 1972, and isc now occupied by the now the Human Rights Campaign.

A metal sidewalk plaque commemorates Milk. [80]

110. Harvey Milk Terminal 1 (T1C), San Francisco International Airport (SFO), San Francisco,

2018-23.

It is operational now, but will be fully completed in three years. [81]

111. The Wall Las Memorias AIDS Monument (Arch of Hope), Lincoln Park, Los Angeles, 1993 designed by architect David Angelo and artist Robin Brailsford.

This was the first publicly funded AIDS monument in the USA. The Wall-Las Memorials Project’s AIDS monument, targeted to the Latino community, and is about 836 m2 in area.

An endowment fund covers the cost of maintenance. The names submission process is open to everyone, and more names are added annually. [82]

112. Matthew Shepard Human Rights Triangle, Crescent Heights Boulevard &

Santa Monica Boulevard, West Hollywood, Los Angeles, 1999. [83]

113. Mattachine Steps (or Cove Avenue Stairway), Silver Lake, Los Angeles, California, 2012.

The Mattachine Society, founded 1950, is the second earliest gay rights organisations (only Chicago Society for Human Rights, founded 1924, is older) in the USA. [84]

114. West Hollywood Walk (or Memorial Walk), Santa Monica Boulevard (sidewalks between Fairfax Avenue & Doheny Drive, on the east boundary of the City of Beverley Hills), Los Angeles.

Commemorative bronze plaques with the names of those who died from AIDS are embedded in the sidewalk. Funds raised by the purchase of the plaques are used to support the California non-profit Aid for AIDS to assist poor people in Los Angeles County living with HIV/AIDS. Founded in 1993 as the West Hollywood Palms Project, and renamed in 2003, when a keystone was installed by The City of West Hollywood at the northwest triangle at Santa Monica Boulevard and Crescent Heights Boulevard. Names and locations of the plaques can be found at the Aid For AIDS website. [85]

Other California

115 (41). The National AIDS Memorial Grove, San Luis Obispo.

116 (42). AIDS Living Memorial Grove, San Luis Obispo.

117 (43). California Pride App.

[San Diego.

An undated proposal only, though supported by the mayor]. [86]

North Carolina

118. AIDS Memorial Garden, Tanglewood Park, Clemmons, Forsyth County, 1997.

Developed by Senior Girl Scouts, as their Girl Scout Gold Award Project, with local donations and volunteer labour, including HOPE (HIV Outreach Programs and Education), and the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship, Winston-Salem, and the PRIDE Team Member Network of Wells Fargo & Co. [87]

Tennnessee

119. Penny Campbell Historical Marker, 1615 McEwen Avenue, East Nashville, 2017.

Named in honour of the LGBT activist. [88]

120. Jungle and Juanita's Historical Marker, Seventh Avenue & Commerce Street, Nashville, 2018.

In honour of two bars popular with gay men in the 1960s-80s, and raided by police in 1963. [89]

Texas

121. Pink Dolphin Monument, in R A Apffel Park/East Beach, Galveston Island, by sculpture artist Joe Joe Orangias who donated it in 2014.

The Pink Dolphin Tavern was in Galveston. This monument was made in collaboration with writer Dr Sarah Sloane and scientist Dr Frank Pega. It is claimed to be the first monument dedicated to gender and sexual minorities in the southern USA. It was restored after vandalism in 2019. [90]

122. Texas AIDS Memorial Garden and Column, Houston, 1983-86.

The 1.2-hectare garden was built on an abandoned railway line. The column was designed by 3D Planet Architects. Unfortunately, the Mayor of Houston, Anise Parker, ordered its destruction in 2013. [91]

Washington DC

123 (44). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Wall of Remembrance.

124, Dr Franklin E Kameny House, 5020 Cathedral Avenue, NW.

The gay activist's (1925-2011) house, is now on the National Register of Historic Places. [92]

Washington

125. The AIDS Memorial Pathway (AMP), on the plaza over Capitol Hill Station, and the north edge of Cal Anderson Park, Seattle, artist: Horatio Law, and other artists, 2018-20.

Funded by the Seattle Parks Foundation. [93]

Wyoming

126. Matthew Shepard Memorial Bench, University of Wyoming, in front of the Arts and Sciences Building, East Willett Drive, Laramie.

Shepherd (1976-98) was tortured and killed. The bench is inscribed with a plaque, inscribed with 'Beloved son, brother, and friend. He continues to make a difference. Peace be with him and all who sit here.' [94]

B. Queer museums: with memorials

127 (45). Tucson LGBTQ Museum, Arizona.

[National LGBTI Museum, New York, 2015.

Apparently, still only a proposal. There has been no news on it since 2008]. [95]

[Proud Heritage Trust Museum, London 2005.

Apparently, this also still only a proposal. There has been no news on it since 2015]. [96]

C. Queer museums without memorials

[Schwules Museum (Gay Museum), Mehringdamm 61, 10961 Berlin]. [97]

[Leslie-Lohman Museum of Lesbian and Gay Art, 28 Wooster Street, New York]. [98]

[GLBT History Museum, 657 Mission Street, Suite 300, San Francisco]. [99]

[Victoria & Albert Museum, London, Gay and Lesbian Tour (within the museum), 2015]. [100]

[Australian Lesbian & Gay Archives, Melbourne, 1978.

Soon to be contained in the new Victorian Pride Centre, Fitzroy Street, St Kilda to open in late 2020].

[Canadian Centre for Gender and Sexual Diversity (CCGSD), 440 Albert St, Suite C304

Albert Street Educational Centre, Ottawa, 2005] [101]

[Charlotte Museum.

The Charlotte Museum Trust is part of a network of archives preserving lesbian culture for future generations in New Zealand]. [102]

[GLBT Historical Society & Museum, Castro, San Francisco].

[Leslie-Lohman LGBT Art Museum, New York City]. [103]

[Museu da Diversidade Sexual, Sao Paolo, Brazil]. [104]

[ONE Gay and Lesbian Archives, University of South California]

'The largest repository of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer (LGBTQ) materials in the world.' [105]

[Stonewall National Museum & Archives (SNMA), 1300 East Sunrise Boulevard, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, 1972]. [106]

[World AIDS Museum & Educational Centre, NE 26th Street #111, Wilton Manors, Florida, USA, 2014]. [107]

D. Places on heritage registers for queer reasons.

USA

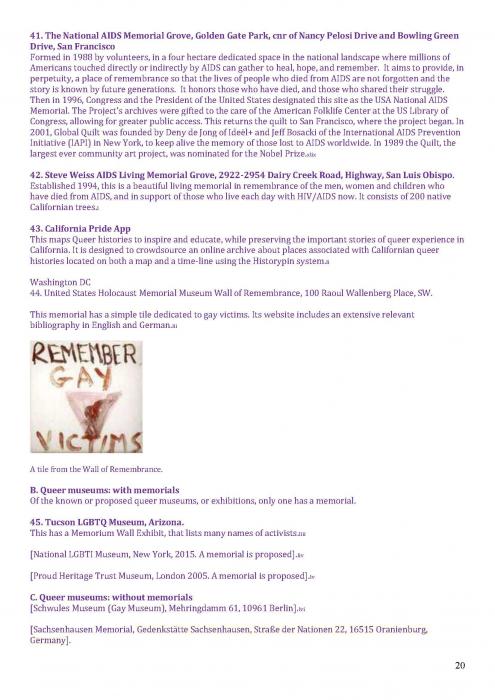

1. Stonewall Inn, 51-53 Christopher Street, Greenwich Village, Lower Manhattan.

Stonewall National Monument: New York, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1999. Its National Monument was created in 2016, by President Obama, a 3-hectare site that includes Christopher Park with its Gay Liberation sculpture (cast 1980, opened 1992) by the famous artist George Segal, and architect Philip N Winslow, and was donated by the Mildred Andrews Fund. It adjoins Sheridan Square, Christopher Grove and West 4th Street.

It will soon include a ranger station and interpretive exhibit, commemorating the 1969 uprising. Except for the Corvid 19 epidemic the bar would still be open for drinks. From 2019, it now contains an initial 50 names the National LGBTQ Wall of Honour of 'pioneers, trailblazers and heroes.' Every year more names will be added. [108]

The Frank Kameny House, Washington DC, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.

The Cherry Grove Community House and Theatre, Fire Island, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2013.

The Carrington House, Fire Island, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2014.

England

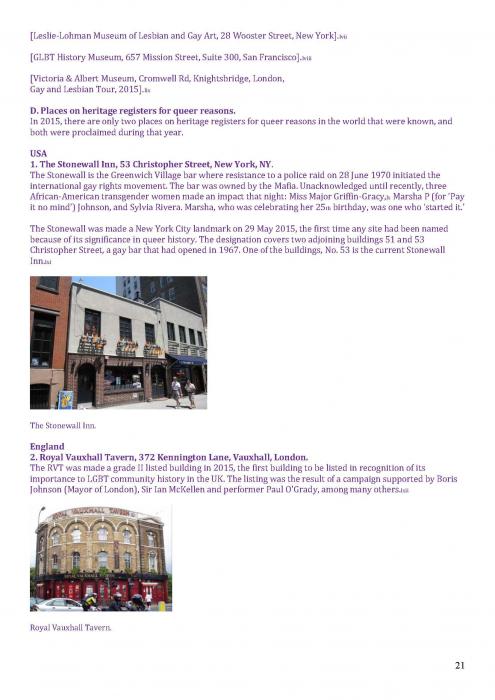

2. Royal Vauxhall Tavern, Lambeth, London.

Presently at risk due to its closure in the Corvid 19 epidemic, and is seeking crowd- funding to survive.

'England's Queer History Recognised, Recorded and Celebrated,' 2016. [109]

Five places have now been relisted by Historic England, one upgraded, and one newly listed. The listings are a result of Historic England’s ground-breaking research project 'Pride of Place,' led by historians at Leeds Beckett University’s Centre for Culture and the Arts, and the Leeds Sustainability Institute. This is part of a major initiative from Historic England to improve understanding and recognition of England’s diverse heritage, tackling under- recognition of the major influences and contributions of communities including LGBTQ, Black and Minority Ethnic Groups, disabled people, and women. [110]

St Ann’s Court, St Ann's Hill, near Chertsey, Surrey, 1936.

The modernist mansion of architect Christopher Tunnard, whose architect was the Australian Sir Raymond McGrath, is being listed by Historic England, as an example of modernist queer architecture. It was designed with a master bedroom that could be separated into two, so that visitors could assume that Tunnard and his partner slept separately.

Amelia Edwards's grave.

Edwards was a Victorian novelist and Egyptologist, and her grave in St Mary’s churchyard, Bristol has been listed for the first time. She advocated for women’s rights in Victorian England. She died in 1892 at the home in Weston-super-Mare that she shared with her partner, Ellen Braysher. They are buried beside each other in a grave inscribed “beloved friend”.

Wilde's home, 34 Tite Street, Chelsea, London.

Wilde lived here with his wife until his trial for gross indecency in 1895; it is being relisted.

The Red House, Aldeburgh, Suffolk.

Britten lived here with his partner, the tenor Peter Pears; it is being relisted.

Shibden Hall, near Halifax.

This was the home of Lister in the early 19th century and is being relisted. She was a pioneer in unashamedly identified herself as being sexually and romantically attracted to women. She inherited Shibden Hall from her uncle in 1836 and lived there for several years with her partner, Ann Walker. [111]

Victoria

Many queer places are protected by heritage overlays, or even on the Victorian Heritage Register,

but there is still nothing protected for queer reasons. Following completion of the 'History of LGBTIQ Victoria in 100 Places and Objects' study later this year, it is hoped that the citations of some places will be amended to reflect their queer history, and new places added.

Comparable other non-queer Australian memorial exemplars

War memorials, avenues of honour, memorial buildings, honour boards.

One additional non-queer Australian memorial that seems relevant:

Bali Memorial, Lincoln Square, Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria, City Architects, 2003.

A large fountain memorial, over 12 metres square, with 150 water jets commemorating the

22 Victorians who died in Kuta in 2002. It was government and City of Melbourne funded, and is inscribed with the names of the victims. [112]

Additions to the Bibliography

[No author known]. 'Pride of Place: England's LGBTQ Heritage,' Historic England, 2016.

A key feature of Pride of Place is an interactive crowd-sourced map hosted by Historypin. Members of the public have placed thousands of pins on the map that identify places that are relevant to LGBTQ heritage and history. [113]

Kasey Jaren Fulwood, 'The National Register of Historic Places and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Heritage,' B.A. Georgia College and State University, 2010. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Historic Preservation, Athens, Georgia, 2014. [114]

A History of LGBTIQ Victoria in 100 Places and Objects, 2019-20.

The Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives (ALGA), commissioned by and in partnership with Heritage Victoria is undertaking a study of LGBTIQ heritage to identify places and objects of significance from the 1840s to 2020 in all regions of Victoria. The study can only include physical buildings and objects that still exist, even if their use has changed. It will be published in July/August 2020. [115]

LGBTQ Heritage Memorial Project, Victoria, 2019-20. [116]

This site is concerned with social history, not with physical memorials.

List of LGBT monuments and memorials, Wikipedia. Accessed: 20 May 2020. [117]

[No author known]. Melbourne HIV Memorial Project. 2013-14. [118]

Adrienne Mortimer, 'Why does LGBTQ heritage matter?' National Trust England, 2017. [119]

Dora Mortimer, 'Blue plaques for LGBT icons is a start, but how do we commemorate the closet?' Guardian, 26 September 2016. [120]

Historic England has now placed relevant plaques on buildings with queer historic connections.

Joseph Oranggias, Jeannie Simms, and Sloane French, 'The Cultural Functions and Social Potential of Queer Monuments: A Preliminary Inventory and Analysis,' Journal of Homosexuality, Vol 65, Issue 6, 2018, published online 2017. [121]

This paper provides a preliminary global inventory of queer monuments and describes three of their functions: to provide visibility and reduce stigma; to educate the public on the abuse and attempted extermination of gender and sexual minorities; and to stimulate public debate about gender and sexual minority rights. Not accessed, due to charge of $AU67.

Richard Peterson, 'Queering Heritage', presentation to Queer Heritage Panel, Heritage Festival, organised by the NTAV with ALGA on 7.30-8.30 pm, 18 May 2018, at Hares & Hyenas.

Richard Peterson, 'Study of LGBTIQ Heritage,' 20 November 2019. Submission to: A History of LGBTIQ Victoria in 100 Places and Objects. [122]

[No author]. 'Prejudice and Pride: Exploring LGBTQ history,' The National Trust (Great Britain).

The National Trust (GB) celebrates the 50th Anniversary of the decriminalisation of homosexuality in England. There is also a LGBTQ podcast series. [123]

[No author known]. Queer Memorials, Wikipedia, accessed 2020. [124]

Ivan Quintanilla, 'LGBT Monuments and Memorials Around the World,' National Geographic, 6 June 2019 [125]

[No author]. Ten Queer Monuments You Must See Before You Die, Orbitz, 2017. [126]

Martin Zebracki, 'Homomonument as Queer Micropublic: An Emotional Geography of Sexual Citizenship,' 2016. [127]

Martin Zebracki, 'Queer Memorials: International Comparative Perspectives on Sexual Diversity and Social Inclusivity (QMem)', Research Project, University of Leeds, January 2018. Case studies: Homo Monument (1987) in Amsterdam, Gay Liberation Monument (1992) in New York City and Tecza (Rainbow) (2012-5) in Warsaw.

Research project, 2018-19. [128]

Martin Zebracki, 'Queerly Feeling Art in Public: The Gay Liberation Mo(nu)ment,' in Candice P Boyd and Christian Edwardes, Non-Representational Theory and the Creative Arts, Palegrave 2019.pp 85-100, first online: 16 March 2019.

Combines auto-ethnographical writing and the found poetry of own fieldnotes, at the Gay Liberation Monument in New York, in the affective relationship between materiality and sexuality in a public artwork; and the relevance of queer theory for queering the representation of public artwork in research practice and output. [129]

References

[1]. Two museums were deleted from the initial 47, as they were only proposals, which have apparently not proceeded.

[2]. Nick Henderson, email to Richard Peterson, 24 May 2020.

[3]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_LGBT_monuments_and_memorials passim

[4]. http://www.artfile.at/artfile/files_e/11.html

[5]. http://www.josken.net/hivaids5.htm

[6]. https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/data/assets/pdf_file/0005/65831/StripOnTheStripBooklet.pdf

[7]. https://www.bondimemorial.com.au/about-the-project

[8]. http://www.josken.net/carring.htm

[9]. https://arts.yarracity.vic.gov.au/gallery/courage

[10]. https://anneriggs.com/2014/07/22/fairfield-house-hivaids-mosaic/); and mural: https://livingpositivevictoria.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Poslink_Issue_025.pdf

[11]. Nick Henderson, email to Richard Peterson, 24 May 2020.

[12]. https://cdn.thorneharbour.org/media/documents/2019-03-March_-_PLC_Newsletter-Web_1.pdf, p 8.

This could not be checked, as access was denied to this document.

[13]. Nick Henderson, email to Richard Peterson, 24 May 2020.

[14]. Justine Dallla Riva of the VPC, email to Richard Peterson, 27 May 2020.

[15]. http://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/disaster/pandemic/display/98990-aids-memorial

[17]. https://www.nationalarboretum.act.gov.au/living-collection/gallery-of-gardens/aids-garden-of-reflection

[18]. https://quilt.ca

[19]. https://www.the519.org/programs/aids-memorial-and-vigil

[20]. https://www.straight.com/life/1121326/historically-hidden-first-known-vancouver-aids-memorial-receive-dedication-ceremony; and http://stanleyparkvan.com/stanley-park-van-memorial-vancouver-aids.html

[23]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Père_Lachaise_Cemetery

[24]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

[25]. http://andrejkoymasky.com/mem/holocaust/ho08.html passim.

[26]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HIV/AIDS_activism and https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

[27]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview.

No other reference to this was found.

[28]. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/AIDS-Memorial_(München) in German and https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

[29]. gaycon.de in Danish.

[30]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument

[31]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/aidsmemorial/namen-project

[32]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

[33]. https://www.bodypositive.org.nz/Pages/Circle_of_Friends/

[34]. https://aidsquilt.org.nz/history/quilt-history/

[35]. https://aidsquilt.org.nz/history/quilt-history/

[36]. https://aidsquilt.org.nz/history/quilt-history/

[37]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tęcza_(Warsaw), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plac_Zbawiciela and https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2018/06/10/poland-warsaw-lgbt-rights-pride-rainbow-water/

[38]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

No other information could be found on this memorial.

[39]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

No other information could be found on this memorial.

[40]. https://www.sa-venues.com/attractionskzn/gugu-dlamini-park.php

[41]. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glorieta_de_la_transexual_Sonia (in Spanish) and https://www.tripadvisor.com.au/Attraction_Review-g187497-d17766742-Reviews-Glorieta_de_la_Transsexual_Sonia-Barcelona_Catalonia.html#REVIEWS

[42]. esmadrid.com

[43]. https://sites.google.com/site/melbournehivmemorialproject/

[46]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview In Spanish.

[47]. https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monolito_en_memoria_a_las_personas_represaliadas_por_el_franquismo_por_su_opción_sexual In Spanish.

[48]. https://www.huelvahoy.com/una-placa-recuerda-a-las-victimas-lgtb-que-suf... In Spanish.

[49]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview. No other reference to this memorial could be found.

[50]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

[51]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

[52]. https://sites.google.com/site/melbournehivmemorialproject/

[53]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview, https://www.blipfoto.com/entry/3944196 and https://pinksaltire.com/2019/09/13/edinburgh-artist-wins-top-award-for-poignant-personal-aids-memorial/

[54]. UK Holocaust Memorial and Learning Centre proposed in 2019 for Victoria Tower Gardens, London, south of Parliament, initially mentioned LBGTI victims. It is not yet erected, and the most recent announcement did not mention LBGTI people.

[55]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_Wilde_Memorial_Sculpture

[56]. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/26/wilde-britten-lister-homes-blue-plaques-gay-culture-2016 and https://historicengland.org.uk/get-involved/visit/walking-tours/queer-soho-walking-tour/

[57]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Turing_Memorial

[58]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Turing_statue

[59]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oscar_Wilde_Memorial_Sculpture and http://www.victorianweb.org/art/architecture/homes/77.html

[60]. https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/monument/hiv/aidsmonument#historic-overview

[61]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plaza_de_la_Diversidad_Sexual

[62]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legacy_Walk

[63]. https://www.aidsgardenchicago.org/belmontrocks

[64]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Turing_(sculpture) and https://siris-artinventories.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?&profile=all&source=~!siartinventories&uri=full=3100001~!328549~!0#focus

[65]. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/christopher-park/monuments/575

[66]. https://archpaper.com/tag/aids-memorial/

[67]. https://glreview.org/article/aids-memorials-in-the-u-s-a/, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HIV/AIDS_in_New_York_City and https://nycaidsmemorial.org/design/

An international design competition was held in 2011, and the work completed in 2016. New York leads the nation in the number of new HIV cases, with more than 2,100 new diagnoses in 2017. More than 125,000 New Yorkers are living with HIV/AIDS, and yet nearly 20% do not know they are infected. So far over 100,000 New Yorkers have died from AIDS-related causes. http://gmhc.org/hiv-info/hivaids-basics/current-hiv-statistics

[68]. https://sites.google.com/site/melbournehivmemorialproject/ and https://hudsonriverpark.org/explore-the-park/art/lgbt-memorial

[69]. https://keywestaids.org/about/

[70]. https://www.facebook.com/AIDSMemorialProjectofNortheastFlorida/, https://www.coj.net/departments/parks-and-recreation/recreation-and-comm... and https://circlescharityregister.com/social-datebook/love-grove-park-grand-opening-aids-memorial-project-of-northeast-florida/

[71]. https://glreview.org/article/aids-memorials-in-the-u-s-a/

[72]. http://washingtonglass.blogspot.com/2008/12/new-orleans-aids-memorial.html; and https://www.out.com/travel-nightlife/city-guides/new-orleans/2013/06/05/faces-glass-and-painted

[73]. Planned from 2013, opened in 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/what-the-provincetown-aids-memorial-leaves-out and http://www.capecodtoday.com/article/2018/06/09/239690-Long-Awaited-P-Town-AIDS-Memorial-be-Unveiled

[74]. https://glreview.org/article/aids-memorials-in-the-u-s-a/

[76]. http://www.namesproject.at

[77]. https://spid.center/en/

[78]. https://aidsmemorial.org/, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NAMES_Project_AIDS_Memorial_Quilt, https://www.hiv-aidsmonument.nl/aidsmemorial/namen-project and https://aidsquilt.org.nz/history/quilt-history/

[79]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvey_Milk_Plaza

[80]. http://www.mycastro.com/castro-camera

[81]. www.flysfo.com/about-sfo/airport-development/t1

[82]. https://aidsmonument.org/ and http://www.thewalllasmemorias.org/las_memorias_aids_monument

[83]. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-oct-13-me-21910-story.html

[84]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mattachine_Steps

[85]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Hollywood_Memorial_Walk and https://web.archive.org/web/20120926134434/http://www.aidforaids.net/walk.html

[86]. https://www.facebook.com/SDAIDSMemorial/

[87]. https://www.forsyth.cc/parks/tanglewood/AIDS_garden.aspx

[90]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pink_Dolphin_Monument

[92]. https://www.nps.gov/places/kameny-residence.htm

[93]. https://www.seattleparksfoundation.org/project/the-amp-aids-memorial-pathway/

[94]. https://www.roadsideamerica.com/tip/25145

[95]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_LGBT_Museum

[96]. https://www.culture24.org.uk/history-and-heritage/art56413 https://books.google.com.au/books?id=fvctCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA148&lpg=PA148&dq=proud+heritage++museum,+london&source=bl&ots=h2sAZ3gRpt&sig=ACfU3U1CKxL1xEOdA4UKRbKvSCE50RppBA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj-8ODKk9bpAhXaXCsKHXgIA-QQ6AEwBHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=proud%20heritage%20%20museum%2C%20london&f=false and https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/15580

[97]. www.schwulesmuseum.de/en/the-museum/

[98]. www.leslielohman.org

[99]. www.glbthistory.org/museum/

[100]. www.vam.ac.uk/blog/va-faces/why-the-va-gay-and-lesbian-tour-is-essential

[101]. https://ccgsd-ccdgs.org/

[102]. https://charlottemuseum.wordpress.com/ The website does not identify its location or founding date.

[103]. https://www.bustle.com/articles/175638-9-lgbt-museums-memorials-around-the-world-you-should-visit

[104]. http://www.mds.org.br/

[105]. https://www.bustle.com/articles/175638-9-lgbt-museums-memorials-around-the-world-you-should-visit

[106]. https://stonewall-museum.org/about-us/

[107]. https://worldaidsmuseum.org/

[108]. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/christopher-park/monuments/575

[109]. https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/news/england-queer-history-recognised-recorded-celebrated/

[110]. https://historicengland.org.uk/whats-new/news/england-queer-history-recognised-recorded-celebrated/

[112]. http://citycollection.melbourne.vic.gov.au/bali-memorial/

[113]. https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/lgbtq-heritage-project/ and https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/lgbtq-heritage-project/lgbtq-architecture/

[114]. https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/fulwood_kasey_j_201405_mhp.pdf

[115]. https://engage.vic.gov.au/history-lgbtiq-victoria

[116]. https://www.facebook.com/groups/275979726366286/about

[117]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_LGBT_monuments_and_memorials

[118]. https://sites.google.com/site/melbournehivmemorialproject/

[119]. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/why-does-lgbtq-heritage-matter

[121]. www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00918369.2017.1364106

[122]. https://engage.vic.gov.au/history-lgbtiq-victoria

[123]. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/why-does-lgbtq-heritage-matter

[124]. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_LGBT_monuments_and_memorials

[125]. This covers memorials in: Tel Aviv; Turing, Manchester; Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism, Berlin; the Legacy Walk, Chicago; Gay & Lesbian Holocaust Memorial, Sydney; Sitges; Amsterdam; and Frankfurt. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/lists/activities/lgbtq-monuments-around-the-world/

[126]. https://www.orbitz.com/blog/2017/03/10-queer-monuments-must-visit-die/

[127]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/tesg.12190.

[129]. https://sites.google.com/site/melbournehivmemorialproject/

---

The paper “Remembering Australia’s Queer Places” was first presented at the 2015 Australian Homosexual Histories Conference, Preserving queer histories – acknowledging, recording, keeping, sharing. Adelaide, 13-14 November 2015. Below the slider in which it appears, can be zoomed in on via your screen so that the text and images are clearer. The images were sourced from Wikipedia unless otherwise stated and are licensed by creative commons.