The last editorial

Yhonnie Scarce often refers to the ‘feelers’ of our project.

Feelers are the animal organs such as an antenna or palp that are used for testing things by touch and in the search for food. As humans we often refer to having a feeling, the sense of which is often denied for the preference of reason. Rather than setting them against each other, we have come to understand, during this year working on and with The Image is not nothing (Concrete Archives) that we are working with our senses: the faculty for which our bodies perceive external stimuli, and also our ability to follow lines of logic and the tangents of our connections as they are made visible and emerge in the conversation and encounters with artworks and artists, writing and writers.

These ‘feelers’ are the emergent and previously unseen lines of connections between the people and places we have encountered, and the contacts made, fostered, stirred and supported. They are visible not only in that which we have published, but also in the exhibition forthcoming, and in the work of those whose authorship is of a different kind.

For Foucault the archive consists of 'the law of what can be said'. For Derrida the archive is not just a material place where knowledge is stored, but it is also a general feature of our mental lives. Ernst von Alphen re-iterates him, in suggesting ‘all human beings suffer from mal d'archive, from archive fever or an archive sickness.’ [1] This compulsion to archive is one of excavating memories. Between Foucault’s discursive site of law, and Derrida’s psychoanalytic base, we find both a 'system of statements' of what can and cannot be said—distinctions and exclusions, as well as the practice of archiving memory and archeologically excavating that which is repressed.

Truth-telling isn't a part of our history. What is a deep-seated part of our history is massacres, denial and erasure of violence committed at the hands of the state. The very same state that commits alleged war crimes in our name overseas. [2]

During a semester facilitated by zoom and google: databases that make visual, collate and collect; one of our students simply yet poignantly rhetorically mused, do we use archives to compensate for our bad memory.

Our bad memories forever being re-written and re-coded, by both will and force, deliberation and accident. The practice of archiving and excavating is the means by which we practice memory—it is neither delineated nor defined. It functions both personally and socially and is a cultural activity affected by surplus and deficits and of a materiality always-already affected and influenced by loss and gain of its technics of collection, storage, dissemination and distribution, as well as by its capital and categories, assets and acquisitions. Collections age, storage reaches capacity, distribution methods become obsolete, categories of distinction are disputed, and the appearance of miscellany muddles a social contract.

The state of most of the Old People, our Tasmanian Aboriginal forebears is relentless, accusatory and unwavering. Captured in nineteenth century lenses of at least eight colonial photographers, permanently present, their gaze is more than only fixed forever at a time, amidst events they should not have experienced. It is something uncanny and comfortable, downright painful to be subjected to. While not direct ancestors, these people are kin, and compatriots. When I look at their faces I see family and feel a lot more than I want to. [3]

We are attempting to approach history, not through hierarchies of information, but through the experiences and relationships of those who encounter the archive and create, unearth, re-frame and re-form the knowledges of exchange found in them, that which we share, or should share, both public and private. Riddled with conflict and contradictions, archives need to be re-examined, rearranged and rethought in order to discover what is missing. This collection contains artworks that source archives and archives themselves. To draw on one of Ernst von Alphen’s opening statements in Staging the Archive, ‘… 'archival artworks' probe the possibilities of what art is and can do.’ The archive is a site for productive contradictions; mal d'archive is both sickness and affirmation just as pharmakon denotes remedy, poison, and scapegoat, sickness implies a host has been dominated and also affirmed.

Concrete, the term, has an interesting etymological journey moving from the past participle of concrescere ‘to grow together’ to a logicians' term in opposition to abstract and meaning ‘expand’. Our experiences travelling—through place and through research—parallel these definitions. Perhaps we realise now, that the socialist modernist spomeniks of former Yugoslavia and the articles and artworks we have collected, both form a mass of concretion, one via sediment the other through language (be it image or written in form): projects of and for memory be they commissioned by the state or revived by the people. Our Concrete Archive is part of a network that image science operates in. Images and information in relation to each other. To remember, drop one:

The image is neither nothing, nor all, nor is it one—it is not even two. It is deployed according to the minimum complexity supposed by two points of view that confront each other under the gaze of a third. [4]

This is the last editorial, but we began in the middle and are still far from an end.

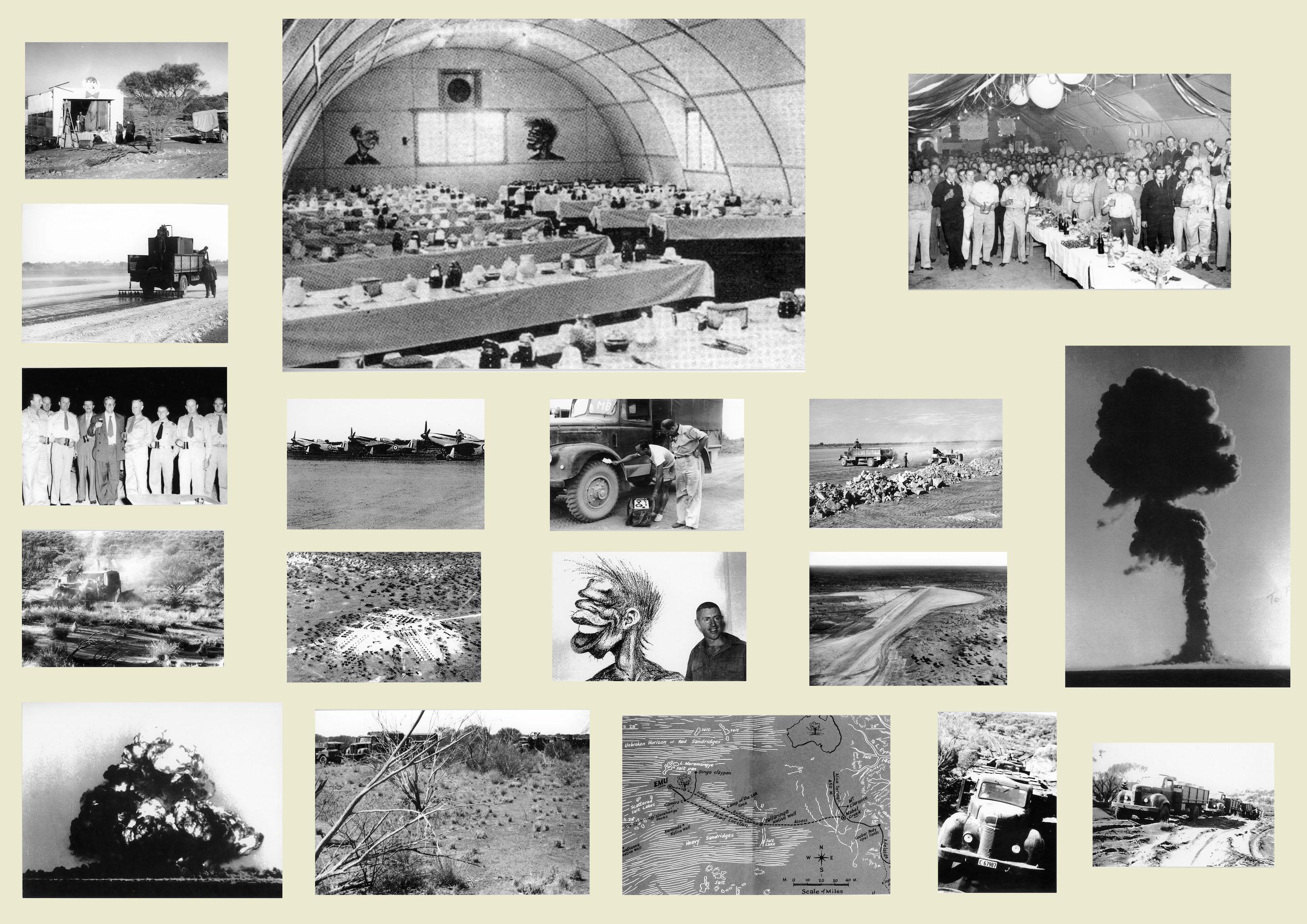

Once again we speak to this relationship between image and data, information and experience in a project traversing relationships between science and the nation state, military capitalism and memorialisation, the conflict in systems of management and the ignorance and arrogance of destroying cultural information.

The site was within the Great Victorian Desert to the North of the Nullarbor Palin. The Len Beadell (sic) exhibition also found and remarkable evidence of Aboriginal civilisation — what Chief Scientist Alan Butement, with Beadell at the time, described as the “Aboriginal Stone Henge”’. This arrangement of numerous piles of large and smaller stones and slivers of shale seemed to form an enormous arrowhead on a vast claypan between Emu and Maralinga. But, noted Butement “there was no time to make a detailed study of the area”, and that was that. [5]

Andy Butfoy has kindly helped us to update the timeline we reprinted from the catalogue for the exhibition Nuclear R(age), a survey of the Bomb and nuclear economy in Australian art, at Monash University Gallery, beginning in 1945 and ending in 1995, it now expands to our present. Azza Zein has paralleled the political and geographical data with the artists, artworks, writings, and research excavated this year on the nuclear.

Daniel Browning provides the background for a forthcoming ABC Radio National documentary Tracking Emu, in his essay Like a fog. Browning collects and collates the experiences of the Aboriginal people, communities and families the tests affected alongside historical and scientific accounts from national media sources evidencing Justice James McClelland finding that the area where the tests were formed was hardly unoccupied during the Royal Commission into the British nuclear tests in Australia (1984-1985).

Karina Lester’s speech to the UN to negotiate a treaty banning nuclear weapons in 2017 cites her families direct experience of the tests at Emu Field and the disproportionate impact of nuclear testing on indigenous peoples throughout the world. As she states, ‘Indigenous communities have borne the brunt of these deadly experiments. Our land our sea our communities and our physical bodies carry this legacy with us now and for unknown generations to come.’[6] The Nuclear Map visualises the scale of Lester’s remarks.

The term Nuclear Colonisation was coined in 1992 by US anti-nuclear weapons testing activist Jennifer Vierreck, who described it as ‘the taking or destruction of other peoples natural resources, lands and well-being for ones own in the furtherance of nuclear development’. [7] As Elizabeth Tynon states, in effect the democratically elected prime minister of Australia decided to lend Australia (comprising of stolen and unceded land) to the United Kingdom, without consent of its people: the genocidal legacy of Terra Nullius deployed to full effect.

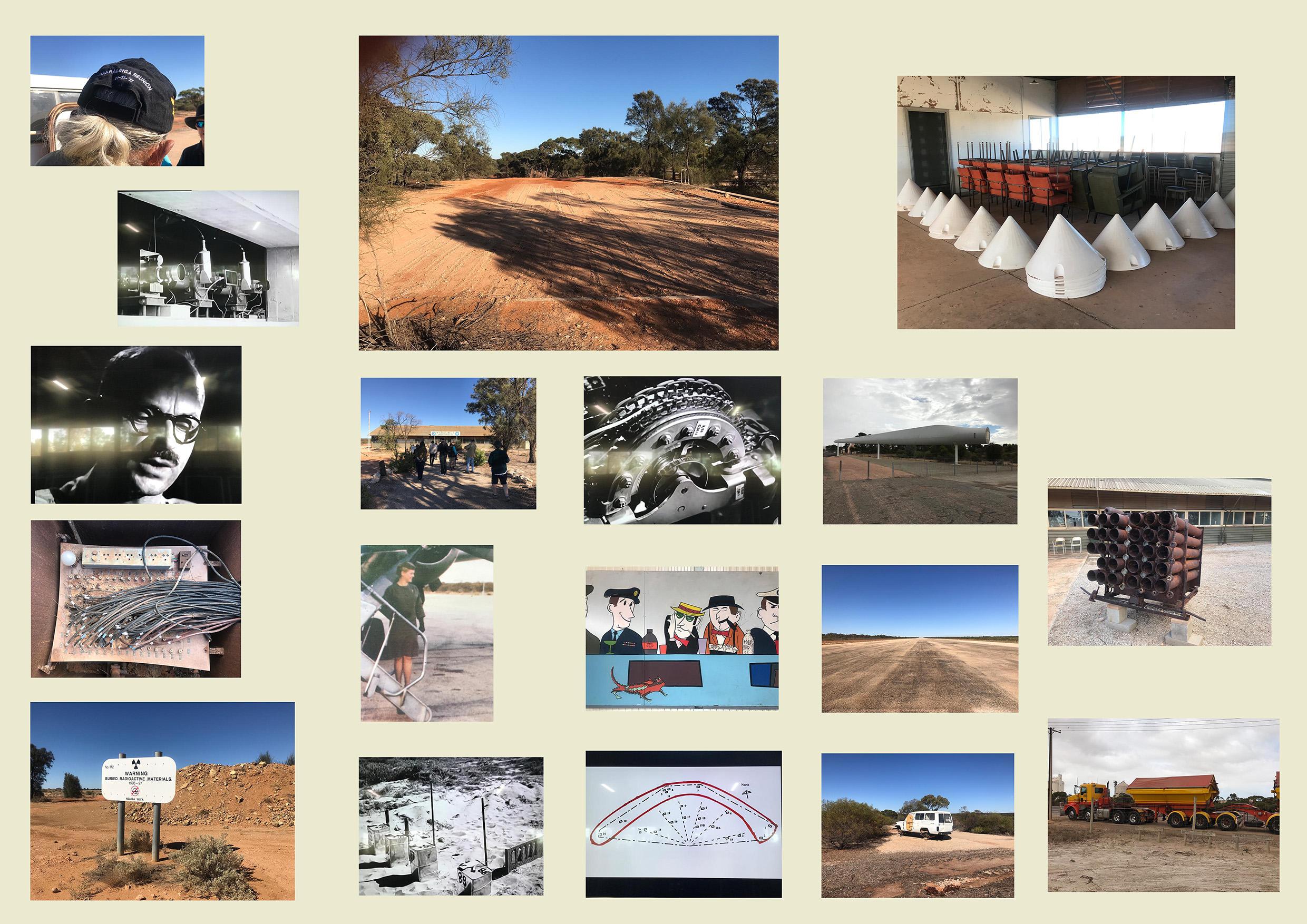

When Yhonnie and I travelled to Maralinga in April of 2019, Uncle Robin, caretaker and tour guide points to a map of the area and recounts the source of water and experience of the area known to Maralinga Tjarutja people and their relation to governance and the state:

His name was Walter MacDougall, he was the native patroller. There was no other good people anywhere on the land here. 2500 kilometres of dirt roads, and he could ride 2500 kilometres of dirt roads in 10 days easy. But how would you go, getting in through the scrub and everything. You're driving on dirt road. And drive fast, and then walk down and a family under the bush. He didn't see them. And all of a sudden then, just poke your head up, wonder what that vehicle is there going down the road. It's physically impossible to get everybody off the land in 10 days.

Uncle Robin continues:

So yeah, that was 117 documented cases that he recorded of people being turned around that never went anywhere. They never came back or... Just disappeared. That's the people he found. What about the people he didn't find?

What about the people he didn’t find?

There is a fundamental link between memory and the nation. This link is made visible in the decisions the state makes with regards to who and what are remembered, how and to what scale. As Jeffery Olick observes, national memory and historiographical nationalism can be challenged by recognising that the nation is an identarian as well as political form. Pierre Nora in 1989 writes ‘We speak so much of memory, because there is so little of it left.’ [8] Thirty-one years later, this memory is recorded, built, revived and transmitted in ways that can more easily challenge the dominant historical narratives of the nation and the purposes that these narratives and illusions to descent might serve. But, at the same time, the accelerated and individuated technological forms that transmit and transfer these memories, run the risk of alienating negotiated and shared collective forms. Memory and history need not be conflicting forms, in fact, Daniel Browning’s essay poignantly serves to demonstrate how both memory and history are responsibilities shared by communities demonstrating that what was thought to be violently erased, has not been.

This is not a reconciliatory project, it is a social one that attempts to keep in play that which legacies of colonisation and settler mentalities have attempted to nullify. The people Walter McDougall didn’t find, we hope, can be felt in the action of this archive, ongoing and incomplete.

We can’t thank enough the dedicated support and work of our colleagues Freya Pitt and Azza Zein, who became co-authors and contributors as we counselled and conversed our way through contributions consisting of links, images, texts and artworks, the producers of which we would also like to acknowledge. And very importantly, we would like to thank Vikki McInnes and the Art + Australia board for inviting us, without restraint, to edit this edition it is her trust in our ‘emergent’ and ‘feelers’ approach to gathering, analysing and representing that has supported and empowered not only us, but also, we hope, our colleagues and contributors.

[1] Ernst van Alphen, Staging the archive : art and photography in the age of new media,

London : Reaktion Books, 2014, p. 13.

[2] Diana B. Sayed, Australian crimes in Afghanistan weren't just a 'few bad apples', we're rotten at our core,

[3] Julie Gough, Forgotten Lives – The first photographs of Tasmanian Aboriginal People in Jane Lydon (Ed), Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2014, p. 21

[4] Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All, The University of Chicago Press, United States of America, 2003, p. 151.

[5] Elizabeth Tynan, Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga Story, Newsouth, 2017, p.93.

[6] Karina Lester, https://vimeo.com/221944177, accessed 1 November, 2020.

[7] Elizabeth Tynan, Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga Story, Newsouth, 2017, p.3.

[8] Jeffrey K. Olick, Memory and the Nation: Continuities, Conflicts, and Transformations, Social Science History , Winter, 1998, Vol. 22, No. 4, Special Issue: Memory and the Nation (Winter, 1998), pp. 377-387

With thanks to Vikki Mcinnes, Maddee Clark, James Nguyen, Nguyen Thi Kim Nhung, Romaine Moreton, Rodney James, Peter Booth, Lyn Onus, Charlotte Day, Andy Butfoy, Yirrkala artists (Dhuwa Moiety and Yirritja Moiety), Will Stubbs, Glenn Worthington, Geoff Hogg, Tristan Harwood, Jimmy Pike, Jimmy Pike Estate, Pat Lowe, Jack Green, Jonathan Jones, Lauren Burrow, Sarah Walker, Katherine Aigner, Ele Carpenter, László Moholy-Nagy, Natalie Harkin, Simon Starling, Yasuo Miichi, Omar Sakr, Bundoora Homestead, Andy Butler, Siying Zhou, TextaQueen, Diego Ramirez, Khadim Ali, Hayley Millar-Baker, Nabilah Nordin, Phuong Ngo, Steven Rhall, Richard Peterson, Julie Gough, Neika Lehman, Jessica Walters, Libraries Tasmania, Stephen Thomas, Flying Carpet Films, Ricky Maynard, Bett gallery, Lyndall Ryan, Judy Watson, Jacob Warren, Milani Gallery, Michelle Keown, PREL, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, Dan Lin, Ti Parks,The Estate of Ti Parks, Kate Nodrum, NGV, Pip Morrison, Sigourney Jacks, Nicholas Umek, Gary Sommerfield, Phillip White, Ieva Kanepe, Judith Ryan, Ti Parks Estate and Family, Kate Nodrum, Sue Jammet, Sam Parks, Te Papa, Estelle Best, Raafat Ishak, Stanislava Pinchuk, Claudia Arozqueta, Daniela Edburg, Pedro Reyes, Raul Ortega Ayala, Déwé Gorodé, Deborah Walker, Raylene Ramsey, Noi Sawaragi, Jason Waite, Don’t Follow the Wind, Naohiro Ukawa, Bontaro Dokuyama, Hikaru Fujii, Meiro Koizumi, Chim↑Pom, Ali Cobby-Eckermann, This is No Fantasy Gallery, British Pathé, Jessie Boylan, Andrea Steves, Crunch Kefford, Gem Romuld, Alex Moulis, Yul Scarf, Tessa Rex, Linda Demen, Dr Ponk, Aunty Sue Coleman-Haseldine, Avon Hudson, Russell 'Shane' Bryant, Aunty Rita Bryant, Christopher R. Hill, Barr Smith collection, Anne Hawkins, Joanna Hookway, Samantha Sherbourne, Jeremy McIlwaine, Sam Sales, Bodleian Library, Special Collections, Oxford University, Uncle Robin Matthews, Daniel Browning, Maureen Douglas, Iluwanti Ken, Freddy Ken, Naomi Kantjuriny, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton, Kunmanara Kaika Burton, Rupert Jack, Adrian Intjalki, Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, Arnie Frank, Kunmanara (Ronnie) Douglas, Errol Morris, Taylor Wanyima Cooper, Noel Burton, Kunmanara (Hector) Burton, Cisco Burton, Angela Burton, Moses Brady, Freda Brady, Stanley Douglas, Keith Stevens, Yaritji Young, Marcus Young, Kamurin Young, Frank Young, Carol Young, Anwar Young, Mumu Mike Williams, Ginger Wikilyiri, Mr Wangin, Lyndon Tjangala, Graham Kulyuru, Lydon Stevens, Mary Katatjuku Pan, Kevin Morris, Mark Morris, Bernard Tjalkuri, Kunmanara (Tiger) Palpatja, Kunmanara (Willy Muntjantji) Martin, William Tjapaltjarri Sandy, Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Kunmanara (Ray) Ken, Kunmanara (Brenton) Ken, Witjiti George, Sammy Dodd, Mick Wikilyiri, Priscilla Singer, Pitjantjatjara/ Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Alec Baker, Margaret Ngilan Dodd, Eric Mungi Kunmanara Barney, Peter Mungkuri, David Pearson, Kunmanara (Jimmy) Pompey, Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Jimmy Donegan, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Pepai Jangala Carroll, Michael Bruno, Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia/Luritja people, Northern Territory; Roma Young, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/ Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Aaron Riley, Adrian Riley, Walpiri people, Northern Territory; Vincent Namatjira, Western Arrernte people, Northern Territory, Art Gallery of South Australia, Letti Koutsouliotas-Ewing, Greta Wass, Australian War Memorial, Karina Lester, ICAN and Andy Butfoy.

The title image is a digitally processed version of an original photograph showing the mess hall at Emu Field with an offensive caricature of an Aboriginal man. Courtesy of private collection.