The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

The recent surge of AI-generated art raises many legal questions. Historically, when dealing with new, fast-developing technology, the law developed slowly and often in hindsight as it grappled to keep up. As we look at the current legal issues surrounding copyright and AI- generated art, it's useful to look back at the historical development of the law regarding photography as the technology became more ubiquitous.

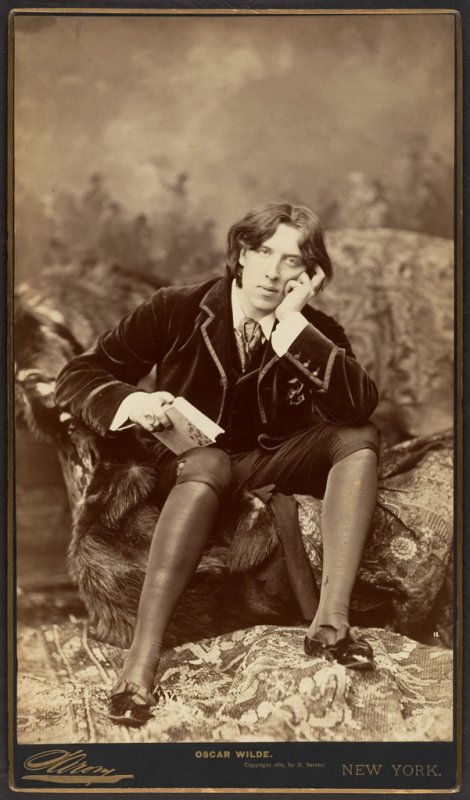

When use of the camera grew in the mid-1800s, artists debated whether copyright should protect photographic works. Photography was considered 'the pencil of nature'1 and some French artists at the time advocated that a camera was a mechanical device that exactly captured God’s work, and so photographs should not be protected by copyright, or if protected, then God should own the copyright.2 In 1884 in a case concerning a photograph of Oscar Wilde taken by Napoleon Sarony, the U.S. Supreme Court considered whether Congress had power to extend copyright protection to photographs.3 The infringer, the Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company, unsuccessfully argued that photography was merely a mechanical process rather than an art. The question as to whether the products of photography constitute artistic works would be fiercely debated to the end of the nineteenth century. Even today this debate continues—French law draws a distinction between artistic photography (which is protected by copyright) and photographs of a documentary nature e.g. of a sporting event (which are not protected by copyright).4

In this new age of AI generated art, a familiar debate is occurring. AI can now create images that, at times, are indistinguishable from human-made art, raising questions about the nature of creativity, ownership and responsibility. We are in the early days of this debate.

Like the nineteenth century arguments regarding photography, some lawyers are advancing the view that AI generated art should not be protected by copyright.5 Because copyright is designed to encourage creativity, it is argued that a computer does not need a legal incentive to create and therefore AI-generated works should not have copyright protection.

...Additionally, if copyright were to arise, who owns it? A computer cannot own property. Many different people are involved in creating an AI work—those who write the program, collect the data, train the algorithm, use the program. Under these circumstances the argument is: it is impossible to decide who should own any copyright in the output created in such a complex way, and that those involved are not “creative".

These are Chicken Little arguments that ignore history.

Just like the use of a camera, an AI machine can be used to create both great and mediocre works. Human artistic skill is needed to use AI to create meaningful AI generated art. Why should this artistic skill not be recognised by copyright law?

How should we think about creativity in the age of AI? As we learn more about creativity and the use of AI, we can then determine what roles in the generative process can be understood as creative, which require incentives or deserve protection, and thus who should own the copyright.

U.S. Artist Jason Allen, who won first prize in the Colorado State Fair digital art competition with his work Théâtre D’opéra Spatial (2022) is appealing the U.S. Copyright Office’s rejection of his request for copyright protection. The Copyright Office said his piece lacked ‘human authorship.’ Allen argues his work, that he spent many hours creating, uses AI as a legitimate tool of artistic expression.

After this rejection, the U.S. Copyright Office then released new guidelines in March 2023 allowing AI generated works to receive a copyright registration in certain circumstances, considered on a case-by-case basis. There must be a human author, the AI must only be 'an assisting instrument', and the artist or author must provide original mental conception to which the artist or author gave visible form.6 The guidelines are vague and attempt to apply old principles to new circumstances. According to the Copyright Office, 'many stakeholders still have questions about these guidelines for works containing AI-generated material and would like more details and more examples of how the Office will approach applications for such works.'7

Like AI art, many people are involved in creating a motion picture—the screenwriter, the cinematographer, the actors, the director, the set designer, the composer of the musical score, the financier—and motion pictures can include computer generated special effects. Despite this complexity, Australian copyright law says that copyright in a motion picture is owned by the producer unless there is an agreement to the contrary.

For over 100 years, intellectual property law has been able to determine who is making the intellectual contribution in respect of complex works. For example, patent law has sophisticated rules to determine inventorship. If I design a fast rocketship and sketch out the plan, but you build it with your welding equipment, generally I will be recognised as the inventor. When Christo and Jeanne-Claude surround islands in pink plastic in Surrounded Islands (1983), the copyright is not owned by the teams of people rolling out the plastic but by Christo and Jeanne-Claude who created the design.

The debate should focus on who is creating or adding artistic value, and thus who should own the copyright to AI generated art. Who is the ‘creative producer’ of AI generated art? Let’s not focus on the minutiae of what the law is today, but what the law should be tomorrow, consistent with long standing intellectual property principles.

It is important to start thinking more deeply about the legal implications of AI generated art, so that we can ensure that artists are fairly compensated for their work and that the public has access to this new form of art.

The flip side of ownership is infringement. When training an AI machine, existing copyright protected works are used as input. There are cases before the courts that will soon consider whether the process of training an AI machine using the copyright works of others or the output of such trained AI machine is copyright infringement.8

Even without the AI overlay, copyright infringement of artistic works is a hard topic. Copyright protects the expression of ideas but not the idea itself. This idea/express dichotomy is at the heart of copyright to provide the balance between protection and progress. It is often difficult to apply.9

It is not copyright infringement to paint a work in the style of Mark Rothko or paint in the abstract expressionism style. It is likely copyright infringement to copy a Rothko’s painting and then modify it. If all of Rothko’s painting are fed into an AI machine for training, and then the AI machine is asked to produce a Rothko-like work, this feels like infringement. However, if all the abstract expressionism paintings in the world are input, and the AI machine is asked to produce an abstract expressionism-like work, this feels more like research or the copying of an idea.

From a strict Australian copyright position, even copying one work as input into an AI machine is likely infringement of that work. This makes the legal training of an AI machine somewhat problematic, unless one only wants to train the machine using old masters where the copyright has expired.

This is where Silicon Valley has changed the rules. Google copied the whole Internet, distributed copyright videos on YouTube, and scanned millions of books in libraries. It just did it. At the time, I took the view that Google was the biggest copyright infringer in the world’s history, and got away with it by dealing with the legal consequences after the fact.10 The AI industry, based in Silicon Valley, is taking the same approach, and is asserting that training AI using copyright works of others is fair use.11 Unless you own or have licensed a large portfolio of works, the only practical way to train AI is to copy existing works. However, this time, copyright owners are on the front foot bringing lawsuits early in the commercialisation process to make sure they get a piece of the pie.

Lawmakers will have to consider whether the artists, whose works are part of the massive data sets computers rely on to generate their results, should be credited and compensated.

I predict that the Silicon Valley AI tycoons will negotiate with copyright owners and collecting societies to pay royalties to use existing works to train AI, unless the tycoons successfully lobby the government to amend copyright law to allow the training of AI without a license. Artists should make sure to be pro-active in this process. Hollywood writers are currently striking, concerned about AI reducing their income, Lawyers are also worried too, for similar reasons.

AI is also enabling new forms of expression. An example is deep fake videos, often in the form of comedies or mockumentaries. A video work can be created that makes it appear that Albanese and Trump are doing the most ridiculous things, and that looks real. This could be art, or political commentary, or both. Or it could be used for improper purposes.

Research is also taking place to tap in and mirror our dreams using AI. By measuring brainwaves when we sleep, AI appears capable in the not-too-distant future of producing a video of our dreams.12 If the mirror is a tool for self-discovery helping us to learn more about ourselves and our place in the world, then in the age of AI, this new ‘mirror’ may provide the most intriguing view of the human soul.

In short, AI will be used to generate new forms of expression that challenge our understanding of what is real, what it means to be human, and the resulting issues of legal responsibility.

Just as the camera resulted in the development of privacy law in the 1890s, AI may result in the creation of new fields of law to deal with responsibility, truth and ethics in AI. The balance between creative expression and responsibility will be tested.

1. Christine Haight Farley. 2004. "The Lingering Effects of Copyright’s Response to the Invention of Photography." University of Pittsburgh Law Review 65 (3). https://doi.org/10.5195/lawreview.2004.10.

2. McCauley, A. 2008. "‘Merely Mechanical’: On the Origins of Photographic Copyright in France and Great Britain." Art History 31: 57-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2008.00583.x.

3. Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884). The UK Fine Acts Act of 1862 had already extended copyright protection to photographs in England two decades prior.

4. CA Paris, pôle 5 ch. 2, 24 févr. 2012, n° 10/10583 (photographs of sports events not protected by copyright; moral rights infringement found). https://www.doctrine.fr/d/CA/Paris/2012/R1E3E47443DD1B7195548. Australian, UK and US law does not draw this distinction, where factual and documentary photographs are protected by copyright. For example, Corby v Allen & Unwin Pty Limited, [2013] FCA 370 (24 April 2013) (photographs of Schapelle Corby taken by family members).

5. Vézina, Brigitte, and Brent Moran. "Artificial Intelligence and Creativity: Why We're Against Copyright Protection for AI-Generated Output." https://creativecommons.org/2020/08/10/no-copyright-protection-for-ai-generated-output. Zurth, Patrick. "Artificial Creativity? A Case against Copyright Protection for AI-Generated Works." UCLA J.L. & Tech. 25 (2020-2021): i.

6. "Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence." https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/03/16/2023-05321/copyright-registration-guidance-works-containing-material-generated-by-artificial-intelligence.

7. "ICMYI: The Copyright Office Hears from Stakeholders on Important Issues with AI and Copyright." Copyright Office Blog, July 2023. https://blogs.loc.gov/copyright/2023/07/icymi-the-copyright-office-hears-from-stakeholders-on-important-issues-with-ai-and-copyright/.

8. For example, Getty Images is suing Stablility AI in Delaware and in the UK. In Tremblay v. OpenAI Inc., two authors claim that ChatGPT can summarise their books, suggesting that ChatGPT has read and copied their works; Sarah Silverman is suing OpenAI and Meta (Facebook) on a similar basis; Google and OpenAI have recently been sued in different class action lawsuits for training their algorithms using vast amounts of materials copied from websites.

9. For example, in Seafolly Pty Limited v Fewstone Pty Ltd, [2014] FCA 321, the court had to decide whether artwork used on Seafolly swimwear was reproduced by City Beach on its swimwear. The artwork consisted of English roses and other flower arrangements in repeating patterns. The Court said, "The application of the idea/form of expression dichotomy has posed challenges, including in context of artistic works. Opinions not infrequently differ over whether, in a particular case, the line has been crossed." The court found that there was copyright infringement in this case.

10. The consequences were lawsuits, legal settlements, and license arrangements after the conduct has occurred. For example, Authors Guild v. Google, 721 F.3d 132 (2nd Cir. 2015), a case in New York that commenced in 2005 and ended in 2015, Google was sued for digitising books without permission. Google claimed it was fair use to do so. The parties reached a controversial settlement in 2008 (the Google Book Search Settlement Agreement) that was amended and then rejected by the court. The court ultimately found that Google’s conduct was fair use in the United States. In Viacom International, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., 676 F.3d 19 (2nd Cir., 2012), YouTube (now owned by Google) was sued over distributing copyright materials that were uploaded by users to YouTube. YouTube claimed it had no knowledge of the infringing uploads. The case eventually settled.

11. The recent U.S. Supreme Court case decided in May 2023 involving an Andy Warhol painting of Price derived from a Goldsmith photograph reconsidered the fair use doctrine. Such use was found not to be fair use and was a copyright infringement by Warhol. This case will impact whether training AI using the works of others is fair use. Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 98 U.S. (2023).

12. "AI Re-creates What People See by Reading Their Brain Scans." https://www.science.org/content/article/ai-re-creates-what-people-see-reading-their-brain-scans. See also https://sites.google.com/view/stablediffusion-with-brain/. "Seeing Beyond the Brain: Conditional Diffusion Model with Sparse Masked Modeling for Vision Decoding." https://mind-vis.github.io/.

Author/s: John Swinson

John Swinson. 2023. “Artificial Artistry: The Legal Implications Of AI-Generated Art (or Legally, Is AI Art Really Art?).” Art and Australia 58, no.2 https://artandaustralia.com/58_2/p148/artificial-artistry-the-legal-implications-of-ai-generated-art-

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED